In an open field, the soldier had nowhere to hide. Then he became invisible

What in the World, a free weekly newsletter from our foreign correspondents, is sent every Thursday. Below is an excerpt. Sign up to get the whole newsletter delivered to your inbox.

Lviv: I’m writing this week’s dispatch from Lviv, in the far west of Ukraine, where it is possible to walk the narrow streets of the historic centre and feel utterly removed from the war. The shops have put up their Christmas decorations, the central square is beautiful and the traffic moves at a crawl. It is a busy town. If you forget about the world for a moment you can stroll along the cobblestones without thinking about missiles and drones.

But I’m just back from a volunteer centre where people work every day to keep soldiers alive. And I’ve met Nina Synyakivych, a retired teacher, who leads the volunteers in what has become an essential task: making camouflage nets for the army. Seeing them at work, on the third floor of an old building, brings home the fact that this war reaches everywhere in Ukraine.

Retired teacher Nina Synyakivych knows the camouflage nets made by her team of volunteers save lives. Credit: David Crowe

“We want to save our soldiers, our defenders,” Nina tells me. “We save those who save us. We make these nets in order to save not only their weapons but themselves as well.”

I’m talking to Nina while she sits at a desk and cuts camouflage material into long strips, each of them two centimetres wide and two metres long. The colour varies but today it is white: the team is preparing for the onset of winter. There are machines to do some of the work but Nina also works by hand with a pair of scissors.

Behind her stand two rows of timber racks, like the supports for an art display. Black netting hangs from the timber while volunteers weave green, brown or white material into the base to create a sheet of camouflage that runs the length of the room. A handful of volunteers thread the material while they sit or stand at the net, some chatting quietly to each other.

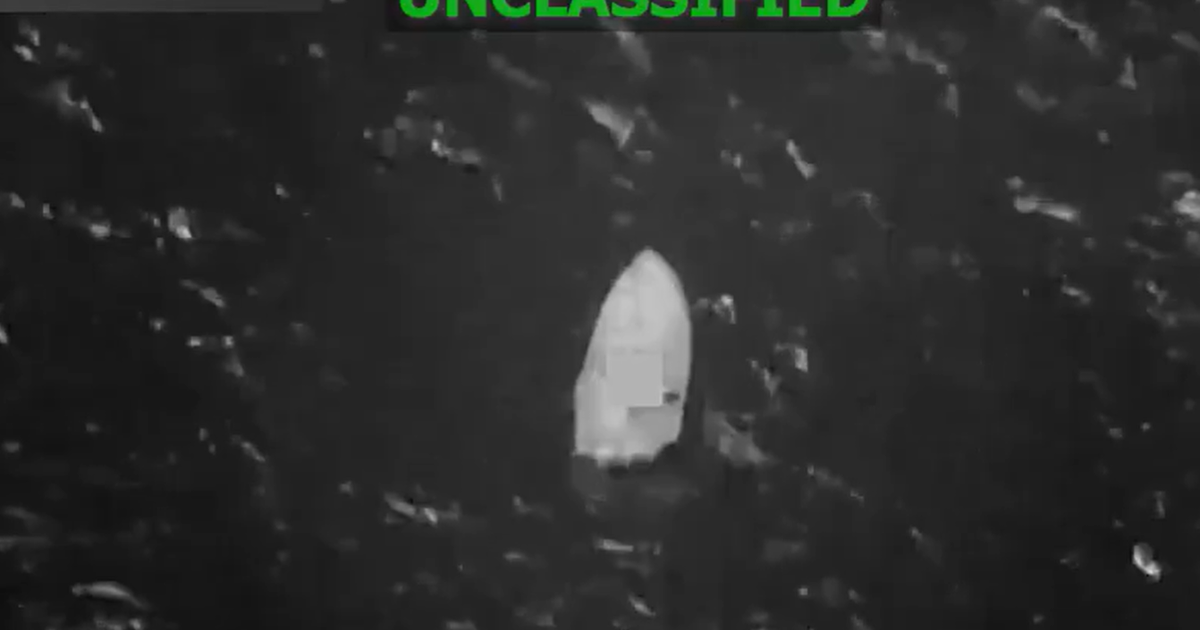

Nina knows the camouflage works. She heard from one soldier who was at the front and knew he was being tracked by a drone in an open field, with no place to hide. “He covered himself by our net,” she tells me in English. “He became invisible.”

I’m not discovering anything new here. After getting back to my laptop I find stories about camouflage workshops from three years ago in The Washington Post and NBC News. You could say I’m covering a “stale” story. But I didn’t have a moment to write about these workshops when I was last in Lviv. And the point is that these centres are still so necessary, almost four years into this cruel war.

In fact, the nets are more valuable than ever. The front line is not really a line any more – it is a broad death zone underneath the drones. Checkpoints are covered in nets and so are city streets. Anywhere a drone can reach is the front line. Army trenches and dugouts need acres of camouflage.

Nina points to a frame on a shelf containing a government award in September 2022 for making the country’s biggest net. She calculates this centre has made about 70,000 square metres of camouflage since Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022. Hundreds of volunteers have worked here – a mix of Lviv locals, people who have moved west to keep their families safe, and visitors from outside Ukraine. The room is open from 10am to 8pm, six days a week. It opens on Sundays when urgent work is needed.

“We are, as volunteers, a family,” she says. “We have lunch together. If someone is absent we want to know why – we will see if we can help.” She doesn’t say this but we all know it: joining a volunteer group can help sustain people under enormous stress as the war goes on.

An Australian in Lviv, Tayissa O’Keefe, told me about this centre when we met over a coffee. Tayissa has Ukrainian heritage on her mother’s side and is on a gap year in Europe, so she is spending a few months in Lviv. The city does not suffer as much as Kyiv and other cities but it has come under attack from drones and missiles. Tayissa finds it positive and almost meditative to work on the nets.

Tayissa O’Keefe, a young Australian with Ukrainian heritage, has joined the volunteer team as part of a gap year in Europe. Credit: David Crowe

“I volunteer because I feel as though I’m part of something very special,” she says. “I’m able to help the soldiers and help the people on the front in a way that I can, and that brings me peace inside.”

It is almost time for me to leave. First, however, I witness the ceremony they hold to mark the completion of a net. Nina calls everyone together and they hold the net flat like a sheet to be folded. A small speaker blasts out the national anthem and the volunteers roll up the camouflage so it can be shipped to the front.

They end with their national cry: “Slava Ukraini!” Glory to Ukraine. They shout the answering cry: “Heroiam slava!” Glory to the heroes. Then they talk happily as they gather around a kitchen table and bring out the food for lunch.

Later, when I tell my family about the visit, my father sends me a message. He remembers my grandmother making camouflage in country Queensland during World War II. It is a reminder of the deep history of European conflict and the sheer endurance it takes to prevail. In an old building in Lviv, far from the front, you can see the two sides of this war: the strength of the community, and the horror it confronts.

Get a note directly from our foreign correspondents on what’s making headlines around the world. Sign up for our weekly What in the World newsletter.

Most Viewed in World

Loading