I’m a forensic psychologist. Here’s how to tell if your child might be an abuse victim

Like most people, I read the allegations that a Melbourne childcare worker sexually offended against children in his care with horror and sadness.

Unlike many though, I have first-hand knowledge about child sex offending, the people who perpetrate it and the way victims respond. As a forensic and clinical psychologist, two of the key groups of people I work with are those who offend sexually against minors, and victims of sexual abuse and violence.

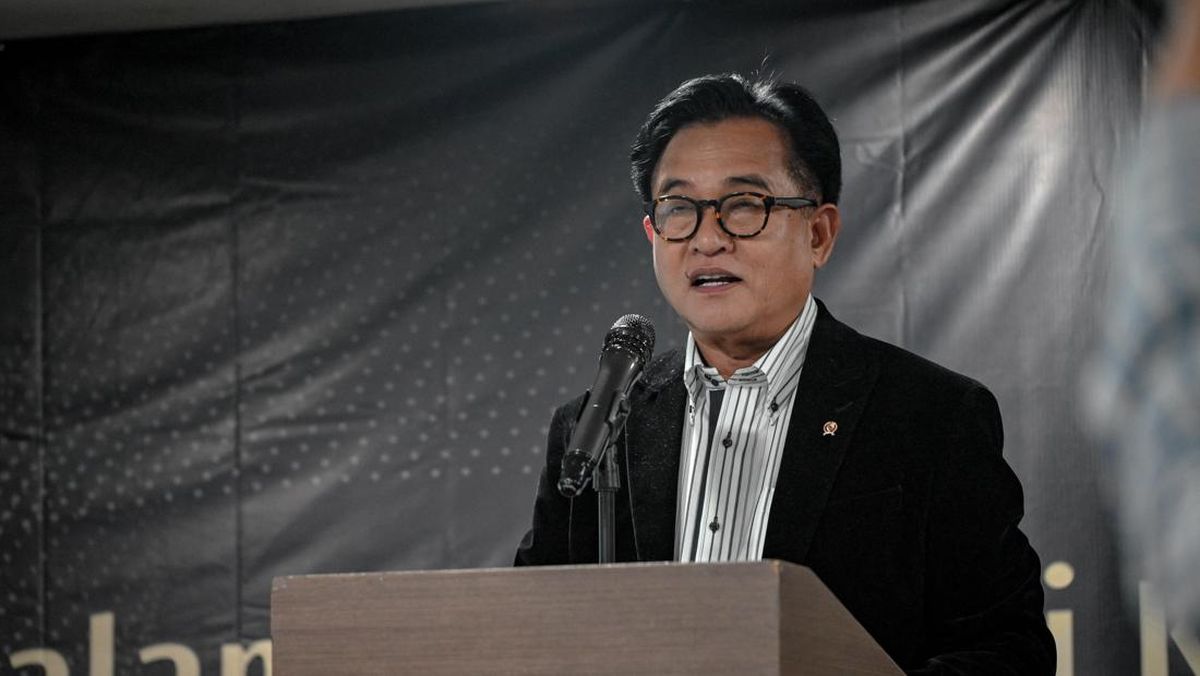

The Creative Garden Early Learning Centre where the accused man had worked.Credit: Justin McManus

Working in this field, you see a lot of darkness. Though brazen behaviours like those allegedly exhibited by 26-year-old Joshua Dale Brown are rare, I have come to realise that child sexual abuse is unfortunately common, with approximately one in four Australians reporting that they were abused as children. This estimate is conservative and does not include online child sex abuse.

Yet while child sexual abuse is common, it’s also hidden, and discussing it is seen as taboo. When the possibility of children being abused is identified, adults – usually their primary caregivers – are often confused and prefer to remain in denial, rather than taking uncomfortable but necessary protective action. This head-in-the-sand approach means that perpetrators remain unidentified and worse, more children are at risk.

When I have run training for organisations around mandatory reporting, common themes include denial that such harms could occur in “nice parts” of the city, or worries about misidentifying innocent behaviour. I’ve also worked with people whose family members and friends have abused children, and common therapeutic themes are initial denial, horror, and a slow realisation that some warning signs may have been present but were discounted – perhaps because we prefer to believe in innocence rather than to see darkness.

Loading

There’s an instinctive sense that we would recognise people who abuse children; that someone like that will be visibly, immediately apparent and different to us. This is a comforting lie, but a lie which comes at the cost of child safety.

The reality is that those sexually attracted to children and those who may choose to harm children look like any of us. They have families, jobs, hobbies and will likely appear entirely normal.

Child safety cannot rely on this instinctive “knowing”. It requires a shared social responsibility that involves legislation, robust organisational frameworks to protect children, and early intervention pathways for those with deviant sexual interests.

The signs of harm are often subtle, but they are unmistakeable: attempts to get a child alone, being overly familiar or crossing boundaries even in minuscule ways, a child saying that someone makes them uncomfortable, an adult attempting to “befriend” a child, children reporting genital pain or redness, secretive online behaviour; all of these are possible warning signs.

The fact is that most children will be abused by someone known to them. Because of this, we need to equip our children to identify harm and report it. Simple protective actions might include ensuring children only attend sleepovers when multiple adults of both genders are present and selecting a childcare with staff ratios that ensure children are not alone with adults. We also need to learn to become comfortable discussing concepts like sex, bodies, good touch and bad touch with children in an age-appropriate manner and equip them with the skills to respond to any harmful or boundary-crossing behaviours by telling a trusted adult. When children are too young to be alert, the onus lies with others to keep a very watchful eye on them.

Loading

The blame for this alleged set of horrific events does not lie with the parents, and it is important for each parent to reassure themselves that they did the best they could and trusted in the systems set up to keep children safe. Allowing self-compassion and placing the blame where it belongs — with the alleged perpetrator — is a more helpful response than becoming caught in shame and guilt.

When horrifying incidents like this occur, it can be an opportunity to examine our collective response and to examine whether we have appropriate safety mechanisms in place. Even the most stringent safety frameworks will be exploited by a determined offender, but there are many actions we can take individually and collectively to keep children as safe as possible.

Primary among these is the recognition that child sex abuse could happen anywhere, in any family, in any suburb, and could be perpetrated by someone who looks entirely innocent and inoffensive.

Remaining alert to this reality is a role that all of us hold.

Dr Ahona Guha is a clinical and forensic psychologist, trauma expert and author based in Melbourne.

Most Viewed in National

Loading