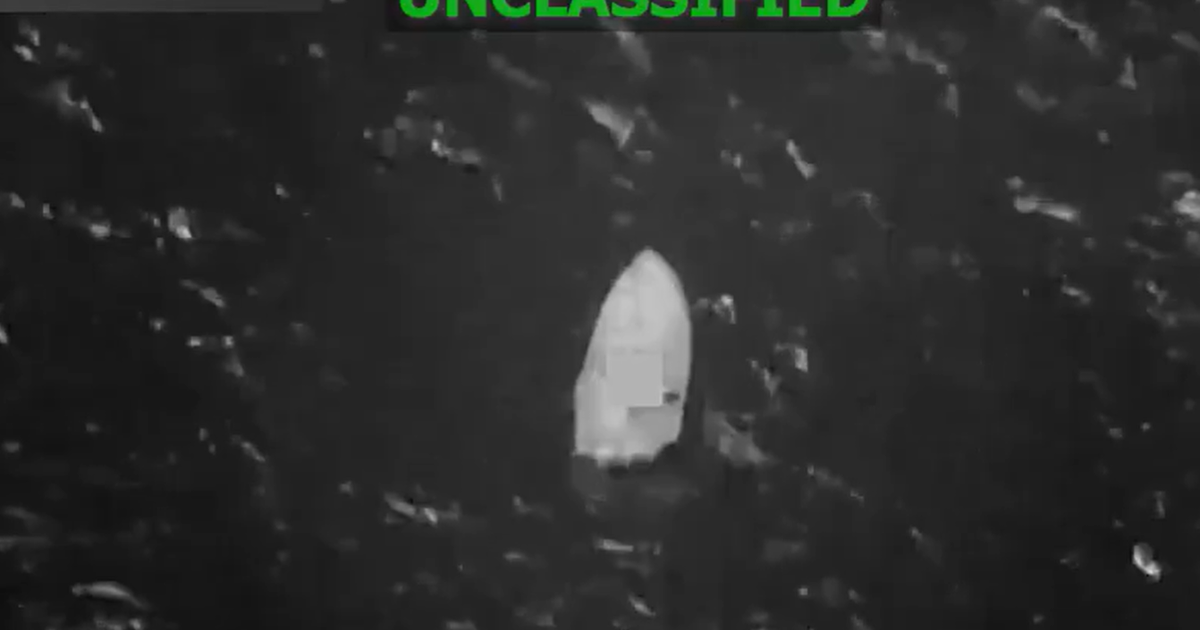

In October 2023, in the lead-up to the Paris Olympics, 20-year-old Australian pro surfer Molly Picklum found herself sitting in the water at a surfbreak called Teahupo’o, on the south-west coast of Tahiti. Teahupo’o, whose name roughly translates as “place of skulls”, is widely considered to be the world’s heaviest wave. Swells from half the world away hit the reef here with deeply malevolent intent, an intensity that pulls the wave into itself, like a black hole. So much water dredges off the reef that the ocean appears to fold over itself: the foot of the wave falls below sea level, creating a warping, cavernous barrel that has been described as a “grinding eye of doom”.

Picklum had only just got into the water when a wave approached, a forbidding blue-black wall the height and width of a small house. Someone close by began screaming at her to commit, but Picklum wasn’t sure. She thought, “I don’t want to die”. In the next moment, however, she decided to go, and was pulled onto the wave by a friend on a jetski. Because Teahupo’o breaks left, Picklum took off on her backhand – facing away from the wave – making it difficult to see how it was breaking.

In a video clip taken on the day, she crouches, arms low, aerodynamic, like the hood ornament on a fancy car. She attempts to exert agency over the wave, to get across it. As the lip throws over her head, the air compresses sharply, producing an unholy aqueous hissing. Right behind her, in the throat of the barrel, a shock wave has produced a car-sized foamball that is sent cannoning into Picklum’s back, blasting her off her board. The last thing you see is an arm, perhaps a leg, her helmet, all going in different directions. From here, she was pushed deep down into the blackness; up, down, sideways, ragdolled across the reef.

Popping up, gasping for air, she found herself in what is called the “impact zone”, the water around her torn with boils and eddies. Another wave bore down, broke, then rumbled over the top of her, sending her cartwheeling underwater for another 30 metres. Again she clawed for the surface. She’d only just got her head above water and snatched a mouthful of air when a third wave hit her, and down she went again. She was breathing water and close to panic when she felt a hand grab her by the helmet and haul her to the surface. It was her friend, on the jetski. He dragged her onboard and throttled down hard, speeding toward the safety of the channel, where the waves weren’t breaking.

“It was the worst wipeout of my life,” she explains. “I had no more fight to give. If there had been one more wave in that set, I’m not sure what would have happened.” We’re standing on the grass overlooking Shelly Beach, her local break, on the NSW Central Coast, an hour-and-a-half’s drive north of Sydney. It’s muggy and grey. The air feels gluey, but there is a gusting offshore and the waves look good, ruler-straight lines marching in from the east. Picklum has already been surfing for hours, but will go out with me again, later. She could easily surf all day, and the next, and the next.

At just 165 centimetres, Picklum, or Pickles, as she is sometimes known, has, at the age of 23, the tomboyish bearing of a pre-teen: hyper-kinetic and unpretentious, with a boundless sense of play and possibility. Since her debut on the world surfing tour, in 2022, she has become one of the sport’s most electric performers.

“She is super fluid, really dynamic and sharp,” says seven-time women’s world champion Layne Beachley. Andrew Stark, Asia-Pacific president of the World Surf League, the governing body for professional surfers, describes her as “talented and fearless”. “She has a blend of relatability and playful doggedness,” surf magazine Stab wrote earlier this year. “She does her best surfing when the going gets rogue.”

This year, after just her fourth year on tour, Picklum stormed the pro rankings, dominating her competitors with courage and creative strategising, and always bringing with her an air of ascendancy. In September, in solid, wind-chopped waves at Cloudbreak, Fiji, she won her final heat, thereby claiming the women’s world surfing title. Interviewed in the water, minutes afterwards, she lay slumped across her board, momentarily shocked into silence, before coming back into her body and letting loose a wake-the-dead victory cry that sounded like a cross between a police siren and a hyena set on fire. “I can’t believe this!” she screamed. “I! CAN! NOT! BELIEVE! THIS!”

The post-win interview went viral, as did her return to Australia, when she stood in the arrivals lounge at Sydney airport, holding aloft the 32-kilogram trophy and yelling, “It’s back where it belongs, baby!” Because of that, I had expected, not unreasonably, that hanging out with Picklum would be an eardrum-busting, white-knuckle ride, like holding a grenade with the pin pulled out. It wasn’t until later, when she started talking about vulnerability, meditation and mastering your mind, that I realised, not for the first time, that I had got this woman completely wrong.

Part of surfing’s mystique is the promise of escape and anonymity, of an obligation-free space ungoverned by commitments. Of course, this doesn’t hold if you’ve just won a world title. In the weeks after her win, Picklum embarked on a series of TV and radio interviews and community appearances. She spoke at corporate events, appeared on podcasts, talked to schoolkids. Keen to leverage her win, Picklum’s sponsors, including Rip Curl, Hyundai, Visa and Red Bull, had her in their offices, meeting staff and hosting Q&As. Then, in late October, she spent a week at a promotional event in Hossegor, a beach town in south-west France. It was a lot, even for Picklum, who, notwithstanding her stamina, is most comfortable at home.

“Heaps of people have told me I should move to the Gold Coast because so much of the surf industry is there,” she tells me. “But you spend eight months on tour travelling from event to event, so when I’m home, I just want to stay put.”

Picklum didn’t come from a surfing family. She was born in 2002, and grew up, the youngest of two children, in Berkeley Vale on NSW’s Central Coast, a quiet, leafy suburb about 15 minutes’ drive from the nearest beach. Her mum, Danielle Smith, worked in sales at Cumberland Newspapers. Her father, Kurt Picklum, was a mechanic and avid sportsman. (He represented Australia in Oztag, a form of touch football, in the 2000s.) Kurt and Danielle split up when Molly was a baby: Molly spent her early teens in shared custody, shuttling between her parents’ houses. “It was a difficult time,” she says. “There were lots of arguments. I had to pack a bag and go to Dad’s on Wednesday, then come back to Mum’s on Monday.”

Both her parents dated off and on during this time. “It was like I had different step-parents, in a sense, which was fun, but then they’d break up. It wasn’t unsafe, but it wasn’t a steady upbringing by any means.” As a little girl, Picklum learnt to be aware of her surroundings – “hypervigilant” she says – and precociously curious. “I’d sit and watch the adults around me, and the way they were living. They were being hindered by external factors, and I decided I didn’t want that. I wanted to control who I was.”

Picklum excelled at sports. She did Nippers at the nearby North Entrance Surf Club, and played Oztag and soccer. “She wasn’t afraid,” says Smith. “She was playing her third game of soccer when she pulled off the most aggressive tackle on this boy, and he just hit the ground.” She was also a talented touch footballer, and even played for NSW as an 11- and 12-year-old.

In 2006, Smith began dating a part-time surf instructor named Brett. Picklum would go with him to the beach, and help push people onto waves. Surfing intrigued her. Of all the sports she’d tried, it was the one that was sufficiently difficult enough to keep her interested. It was also a refuge. “The beach was where it was all right,” Picklum says. “The vibes were more settled than at home.”

Molly Picklum at home on the Central Coast. In 2013, she started surfing every morning “for as long as we could before school”.Credit: James Brickwood

In 2013, Smith and Brett bought a house at Shelly Beach: all that separated them from the waves was the local golf club. Picklum started surfing every day. “We’d run across the golf course in the morning and surf for as long as we could before school.” She joined the local surf club, North Shelly Boardriders, and began taking part in local competitions. Surfing became the only thing that mattered. “There were no boyfriends, no partying,” says Smith, who often accompanied her to contests. “If the waves were good, she didn’t want to miss it.”

But Picklum’s temperament wasn’t always suited to competing. Once, when she was about 15, she crashed out of a local contest at Avoca Beach. She came out of the water, furious, threw away her towel and stormed off the beach. Smith followed her up to her car; Picklum was sitting inside, venting. “I said to her, ‘You can do whatever you want in the car, but you’re not going to be a bad sportsperson.’ ” Learning how to lose, Smith told her daughter, was as important as learning how to win.

Picklum did reasonably well at school: together with her teachers, she planned her study around her surfing. Then in 2016, she was introduced, through a friend, to professional surf coach Glenn “Micro” Hall. A former pro surfer, Hall had recently turned to coaching. (He has since trained some of the sport’s biggest names, including Matt Wilkinson, Owen Wright and his sister, two-time women’s world champion Tyler.) “Molly was talented but technically, she needed help,” Hall tells me. “We worked on the body mechanics of each manoeuvre, and also on learning about different conditions: about how you have to match the right wave type to work on certain turns.”

Picklum was ambitious and driven, and an excellent listener. “Some kids you coach just want to hear how good they are,” Hall says. “But Molly was all ears.” If anything, she was too eager to learn. “She was a bull at a gate,” Hall says. “She was always wanting to do more and do it really well, right now.” But she was naive to the pathways to success, and, in a sport that cherishes its heritage, alarmingly oblivious to its history. One day Hall mentioned American Tom Curren and Australian Tom Carroll, two of modern surfing’s most influential figures. Picklum said something that indicated she had never heard of them. Hall told her: “Please never say that into a microphone anywhere near a competition area.”

‘I was like a plastic bag, easily blown around … like I had nothing inside of me that I trusted or that I was willing to let in. I didn’t know who I was, so I could have been anything.’

Molly PicklumUnder Hall’s tutelage, Picklum made rapid progress. In 2017, at just 14, she won the Layne Beachley Rising Star Award at a talent identification camp at Surfing Australia’s High Performance Centre, at Casuarina in northern NSW. A year later, she took out the Australian Pro Junior women’s title. (She would win it again in 2019.) Rip Curl started sponsoring her; her potential seemed limitless. But despite her success, she rarely felt grounded. “At that time, I felt I had no anchor,” she tells me. “I was like a plastic bag, easily blown around … like I had nothing inside of me that I trusted or that I was willing to let in. I didn’t know who I was, so I could have been anything.”

“Young girls through their teenage years have more to navigate than boys,” Hall says. “Think of the pressures a school environment can create for young girls to feel like they need to fit in, to act and look a certain way and not make any mistakes. And when a young girl starts to be in the spotlight, that is multiplied.” Picklum’s insecurity began feeding into her craving for success. “She was tying her results to her self-worth,” her mother says. “She had to learn to separate those two things, and realise that she was a good person aside from surfing, and that a bad surf was just a bad surf.” When that happened, she would truly become a world-beater. But, as Smith says, “that was a long way off.”

Surfing is an inherently creative and individual pursuit, the aesthetics of which are closely linked to personal expression. It embodies, at its best, grace, flow, power and beauty, a vocabulary more analogous to art than sport. When it’s all going well, it feels rhythmic and seemingly frictionless, as fun as dancing and as free as flying. Picklum isn’t necessarily the most graceful surfer on tour, but she is audacious and wildly improvisational. In competition, it’s hard to take your eyes off her, such is the sense that she is capable – at any given moment – of doing something spectacularly reckless. The approach has served her well: “Part of the criteria of competitive surfing is being dynamic, and unpredictability is eye-catching to the judges,” says Kate Wilcomes, national high performance director of Surfing Australia.

Professional surfing has matured hugely over the past 30 years. Prize money used to be barely enough to get competitors from one contest to another, and sponsorship was threadbare. Today, the top-tier pros earn millions in prize money and commercial tie-ins. They use nutritionists, strength and conditioning coaches, and psychologists. Cross-sport integration is a big thing. Surfing Australia has for several years hosted what it calls “limitless camps”. “We use a lot of jetskis for aerial training and manoeuvres,” says Wilcomes. “We also develop aerial awareness through acrobatics, skateboarding, and watching BMX and motocross. It’s all about innovation.”

Then there is fitness. Picklum is less obsessive about training than some of her peers, but she still works out twice a week, or whenever she isn’t surfing, with Spencer Goggin, a genial, English-born coach who specialises in training surfers and snowboarders. The sessions are aimed at robustness and injury resilience, and involve multiple sets of yoga-like hip and leg extensions, core work with a medicine ball, box jumps, bench pulls and something called “occlusion cuff training”, where Picklum performs dozens of squats while wearing a blood flow restriction cuff – the kind doctors use when checking your blood pressure – around each thigh. “The World Surf League now holds events in wave pools where the waves go for a long time,” Goggin explains. “The idea of the cuff is to simulate that intense leg burn you get when you surf a really long wave.”

Picklum with fans at Sydney Airport after winning the world surfing title. Credit: Edwina Pickles

As in so many sports, much of pro surfing revolves around data points and statistics. The Championship Tour includes 12 events held over nine months, from January through September. During this time, Picklum logs each of her surf sessions, whether in competition or not, into specialised software according to its length and difficulty, on a scale from one to 10. Goggin uses that data to create a “load profile”: “That way, I can design the best workout for Molly when she’s away on tour, focusing on what her exact needs are at any given moment.”

A particularly gruelling part of her regimen is an extreme form of breath work called Breath Mind Body Conditioning. The training, which is conducted by former rugby player and Central Coast local Luke Sullivan, has become a go-to for elite athletes, from Olympic snowboarders to professional lifeguards, and largely consists of underwater wrestling. Participants are held underwater for unfeasibly long periods of time while being spun around, pinned to the bottom, and twisted into ungodly, pretzel-esque shapes. It’s aimed, as Sullivan puts it, “at getting people more comfortable in an uncomfortable situation”, such as when you are drowning. And it works. Sometimes, when she is getting pounded by big surf, Picklum pretends she is “at a party, and I have to dance underwater”.

Picklum and her cohort are among the hardest-working in the history of pro surfing. In 2022, the women’s and the men’s tours were combined for the first time, meaning they surf at the same locations at the same time. This includes spots like Teahupo’o, and the notoriously dangerous Pipeline, in Hawaii, which is thought to have killed or maimed dozens of surfers since it was first surfed in 1961. Despite being only slightly taller than a Shetland pony, Picklum has always performed well in such conditions. In January, 2024, she scored the first-ever female 10-point ride at heaving Pipeline.

In February 2024, she was surfing in the Sunset Beach Pro, in Hawaii, when she caught a bumpy, lumpy, triple-overhead right-hander. Turning off the bottom, she shot up towards the top of the wave before snapping a turn, at the very last moment, right underneath the falling lip. She then began free-falling. Her board lost contact with the wave, and she lost contact with her board. By the time she reached the bottom of the wave, the lip was landing like a bag full of axes, virtually on her head, but somehow she stuck it. Surfer Magazine called it “the turn of the event … maybe the decade”. “I threw everything at it and I kind of fell out of the sky,” Picklum said at the time. “I was either dead or in the final.” She went on to win the event, for the second year running, becoming the first woman to win back-to-back at Sunset since Layne Beachley, in 1999 and 2000.

Every hero’s journey involves a slaying-the-dragon moment. As with so many over-achievers, Picklum’s pet dragon was always self-doubt. She grew up being brutally self-critical and, then as now, a terminal overthinker. It was a combustible combination that worked well for her – until it didn’t. In 2022, midway through her first year on tour, she became so anxious that she almost seized up: she found herself in South Africa, virtually unable to surf. As a circuit-breaker, Glenn Hall, her coach, introduced her to golf.

“She needed to switch off from surfing,” Hall says. “Golf gave her another outlet. It helped her to put her surf analytic brain on hold.” (Picklum still plays occasionally, and is currently in Melbourne for the Australian Pro Am hitting a few – purely recreational – rounds.)

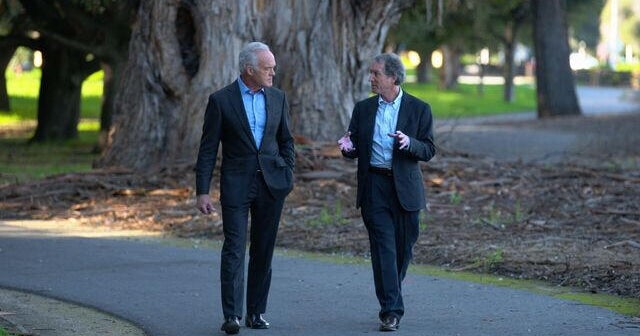

Picklum with longtime coach and former pro surfer, Glenn “Micro” Hall. “Molly was talented but technically, she needed help,” he says.Credit: World Surf League

South Africa was a turning point for Picklum. “I decided to invest more in my mental health,” she says. “I wanted to understand myself better.”

She began meditating; she read widely and listened to podcasts on living purposefully and dealing with imperfection. She particularly enjoyed Brené Brown, an American academic best known for her work on shame, vulnerability and leadership. And she embraced the esoteric, including the controversial self-help book The Secret, of which its central tenet – The Law of Attraction – holds that thought alone can influence objective circumstances within one’s life. “I was willing to try everything,” she says. “I was super curious.”

Loading

In late 2024, Picklum began seeing professional mentor and mindset coach Ben Crowe. “Molly’s challenge was, first and foremost, learning self-acceptance,” says Crowe, who has also worked with former tennis No. 1 Ash Barty, and eight-time women’s surfing world champion Stephanie Gilmore. “She needed to apply self-compassion and let go of what she couldn’t control, which was only distracting her.”

Crowe describes the process as “scary” and “messy”. “You need to unpack your life story,” he says. Picklum says it’s “like going to the doctor. Once you start digging, you find stuff.” But it has proved invaluable. At the beginning of this year, Picklum decided to part ways with long-time coach Glenn Hall. (There was no animosity, and the two are still close.) Instead, she employed a specialist coach at every leg of the tour, tapping into local surfers who were experts at their given breaks, and who could talk her through the intricacies of each spot: the bottom contours, the winds, the swell directions, and so on. “I wanted to feel comfortable in the line-up, and the local people are going to know the waves better than anyone.”

Stephanie Gilmore applauded the move. “I love that she was willing to take a risk and mix it up,” Gilmore told Surfer Magazine. “I think a lot of the surfers rely too heavily on their coaches and support teams to kind of baby them.” Picklum’s strategy paid off. No matter where she went on the tour – Brazil, Hawaii, Bells Beach, Portugal – she surfed out of her skin. By the time she won the world title, in Fiji, there was no doubt in anyone’s mind who was not only the best surfer, but the smartest.

After some logistical snafus, I eventually got a chance to go surfing with Picklum. There is nothing like being in proximity to a world champion to impress upon you the chasmic difference between average and great. With everyday surfers (i.e., me), there is a quantifiable delay between effort and effect. You try to turn, then, if you’re lucky, you turn. But Picklum’s surfing is reflexive and instinctual. She compresses and projects as the moment requires: she flexes, twists, extends. She is rubbery one second, torqued up the next; she reaches places on the wave no human should be. Her surfing is freakishly fast and invariably outlandish, but it is, above all, fun. She is enjoying herself. Nothing is very serious. This is the key.

Loading

At one stage, a rogue wave approached. It was the best we’d seen all day, steep and hollow, its barrelling spitting mist and foam. Neither of us were in position, and we both missed it. As I came up from beneath the wave, Picklum was just ahead of me, and looking over her shoulder, back at the wave. Her eyes were wide and white. “HOLY-SHIT-NO-WAY-THAT-WAS-CRAZY!” she screamed. “Did you see that thing? That, like, FULLY BARRELLED!”

The world champ was a kid again, just a grommet, fully and unashamedly frothing.

Get the best of Good Weekend delivered to your inbox every Saturday morning. Sign up for our newsletter.