Lewis Moody on his MND diagnosis

By

BBC Sport rugby union news reporter

Former England captain Lewis Moody has revealed he has been diagnosed with motor neurone disease and admitted he cannot yet face the full implications of the muscle-wasting condition that killed fellow rugby players Doddie Weir and Rob Burrow.

The 47-year-old, who was part of the 2003 Rugby World Cup-winning side and lifted multiple English and European titles with Leicester, spoke to BBC Breakfast two weeks after learning he has the disease.

"There's something about looking the future in the face and not wanting to really process that at the minute," he said.

"It's not that I don't understand where it's going. We understand that. But there is absolutely a reluctance to look the future in the face for now."

Moody, speaking alongside his wife Annie, says instead he feels "at ease" as he concentrates on his immediate wellbeing, his family and making preparations for when the disease worsens.

"Maybe that's shock or maybe I process things differently, and once I have the information, it's easier," he added.

Moody discovered he had MND after noticing some weakness in his shoulder while training in the gym.

After physiotherapy failed to improve the problem, a series of scans showed nerves in his brain and spinal cord had been damaged by MND.

"You're given this diagnosis of MND and we're rightly quite emotional about it, but it's so strange because I feel like nothing's wrong," he added.

"I don't feel ill. I don't feel unwell

"My symptoms are very minor. I have a bit of muscle wasting in the hand and the shoulder.

"I'm still capable of doing anything and everything. And hopefully that will continue for as long as is possible."

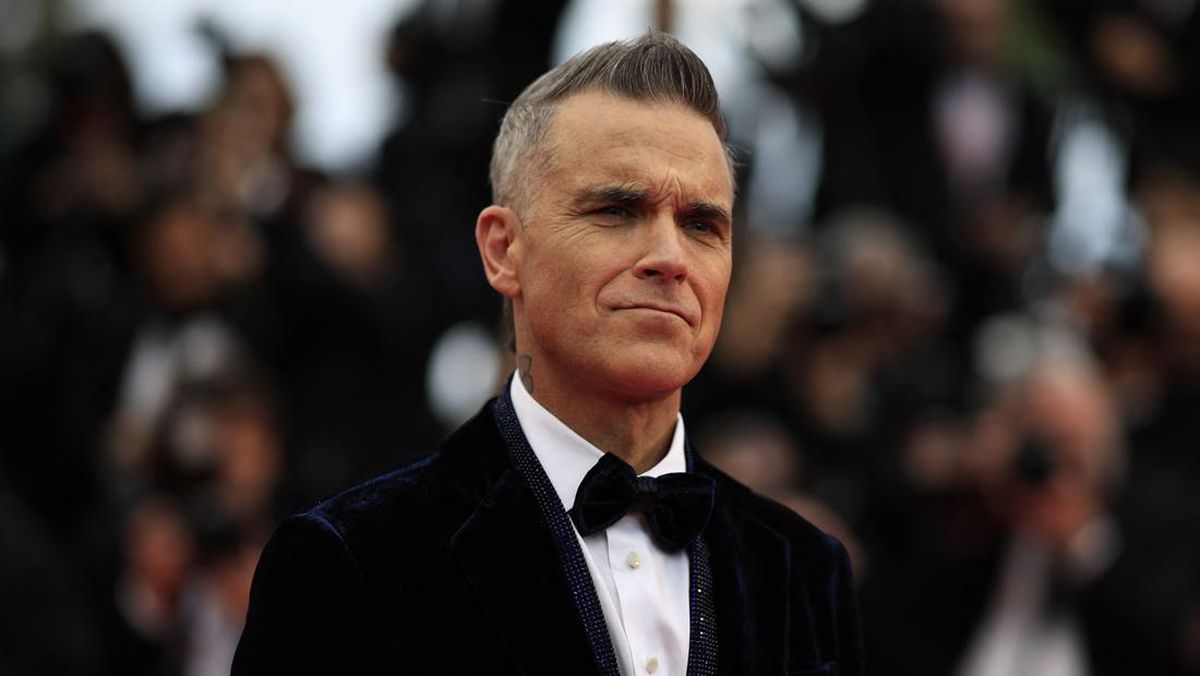

Image source, Rex Features

Image source, Rex Features

Moody won seven Premiership titles with Leicester before departing for Bath in 2010

MND can progress quickly.

According to the charity MND Association, the disease kills a third of people within a year and more than half within two years of diagnosis, as swallowing and breathing become more difficult.

Treatment can only slow deterioration.

"It's never me that I feel sad for," added an emotional Moody.

"It's the sadness around having to tell my mum - as an only child - and the implications that has for her."

Speaking from the family home with his wife and their pet dog by his side, Moody was overcome with emotion when he spoke about telling his sons - 17-year-old Dylan and 15-year-old Ethan - the devastating news, saying: "It was the hardest thing I've ever had to do."

"They are two brilliant boys and that was pretty heartbreaking," Moody said.

"We sat on the couch in tears, Ethan and Dylan both wrapped up in each other, then the dog jumped over and started licking the tears off our faces, which was rather silly."

Moody said the emphasis was staying in the moment.

"There is no cure and that is why you have to be so militantly focused on just embracing and enjoying everything now," he said.

"As Annie said, we've been really lucky that the only real decision I made when I retired from playing was to spend as much time with the kids as possible. We don't get those years back."

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

Moody's eldest son Dylan is a goalkeeper for Southampton and England Under-18s

A knee problem prevented Moody taking up an invitation to play in the inaugural 745 Game last autumn.

The fundraising cross-code match, which brings together league and union stars, was the brainchild of Burrow and Ed Slater, the former Leicester and Gloucester second row who also lives with the disease.

Burrow died in June 2024, while Slater is now in a wheelchair and struggles to speak without the help of a computer programme.

Moody finds it hard to reconcile that he is now part of the match's cause, rather than a supporter.

"It is daunting because I love being active and embracing life, whether it's on the rugby pitch, watching the kids, whatever it is," he said.

"There's a lot of questions around what we need to put in place for the future. It's still so new, I found out two weeks ago.

"I feel slightly selfish in a way that I've been reluctant to reach out to anyone, to Ed.

"But there will be a time when I can. And I would like to as well.

"If they're watching - I'm not ready yet, but I absolutely will [be]."

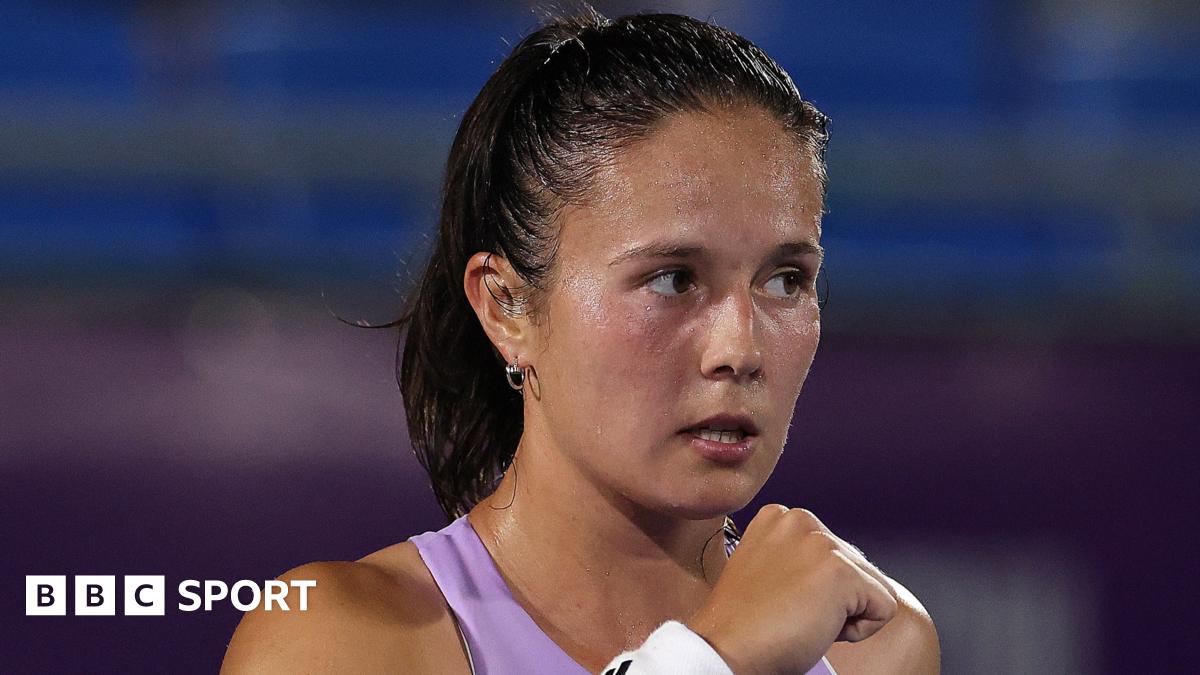

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

Moody (centre, holding trophy) was part of a reunion of the 2003 Rugby World Cup winners who appeared on the pitch at Allianz Stadium last November

Elite athletes are disproportionately affected by MND, with a study of Italian footballers suggesting the rate of the disease is up to six times higher than in the general population.

It is thought that by limiting the oxygen available and causing damage to motor neurone cells, regular, strenuous exercise can trigger the disease in those already genetically susceptible.

Moody, who won 71 England caps and toured with the British and Irish Lions in New Zealand in 2005, was nicknamed 'Mad Dog' during his playing career, in honour of his fearless, relentless approach to the game.

He played through a stress fracture of his leg for a time with Leicester and once sparked a training-ground scuffle with team-mate and friend Martin Johnson when, frustrated, he abandoned a tackle pad and started throwing himself into tackles.

After coming on as a replacement in the Rugby World Cup final win over Australia in 2003, he claimed a ball at the back of the line-out in the decisive passage of play, setting a platform for scrum-half Matt Dawson to snipe and Jonny Wilkinson to kick the match-winning drop-goal.

Moody has already told Johnson, who captained England to that title, and a couple of other former team-mates about his diagnosis, but the rest will be learning his news with the rest of the public.

"There will be a time when we'll need to lean on their support but, at the minute, just having that sort of love and acknowledgment that people are there is all that matters," he said.

"Rugby is such a great community.

"I said to the kids the other day, I've had an incredible life.

"Even if it ended now, I've enjoyed all of it and embraced all of it and got to do it with unbelievable people.

"When you get to call your passion your career, it's one of the greatest privileges.

"To have done it for so long with the teams that I did it with was a pleasure. And I know they will want to support in whatever way they can and I look forward to having those conversations."

2 hours ago

2

2 hours ago

2