There’s one word that comes to mind when meeting the three sisters at the centre of the Malka Leifer case. Endurance.

They endured a miserable home life. They endured sexual abuse at the hands of the principal of the ultra-Orthodox Jewish school they attended. They endured years of trickery, lies and evasion from Leifer and her legal team after she fled to Israel and fought extradition. They endured 74 legal hearings in Israel and so many more in Australia that they stopped counting.

And when Leifer was eventually brought to trial in Australia 13 years after fleeing, they endured day after day of withering cross-examination before their abuser was finally found guilty and sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Now, in the documentary Surviving Malka Leifer, they’re enduring another round of questioning from audiences and journalists and well-meaning friends and acquaintances about the whole interminable mess.

Aren’t you tired of re-opening these old (and not-so-old) wounds, I ask them as we sit around the table of a large house in St Kilda that belongs, they say, to a member of their extended family?

“It hasn’t been re-traumatising,” says Nicole Meyer, 40. “It’s been confronting, and we’ve been transported back to where we were when we were filming. It’s a difficult thing to have our vulnerabilities and rawness up there for everyone to see. But at the same time, there’s a sense of pride that we’ve gone through that, we have something to show through it, and here we are today.”

The film, which screened at the Melbourne International Film Festival and at the Jewish International Film Festival, drops on Stan* on Sunday. And for middle sister Dassi Erlich, 38, getting it in front of a larger audience is vital.

“A big part of the reason for making it, at least for me, was for people to understand that every single person plays a part in the so-called system,” she says. “The way we see sexual abuse, the way we talk about sexual abuse, the way we understand it, the way we treat survivors, respond to it: it’s not this external thing – it’s something we all are a part of, and we all can make change happen.”

And for youngest sister Elly Sapper, 36, the film serves as a record of what they have been through – and, as the title suggests, to the fact they have survived.

Nicole, Dassi and Elly grew up in an ultra-Orthodox household and had a strictly religious education.

“It feels like we’re looking back onto a space that we once were in, as opposed to being in that space,” she says. “We lived and breathed this for so many years, and now it just feels like we can take that breath, take that moment, and look back and be in that new space. Instead of a fighting space, a healing space.”

The documentary from director Adam Kamien and producer Ivan O’Mahoney tells the story of the sisters’ experiences, individually and collectively, from childhood abuse at home, through the betrayal of the seemingly safe haven of school, the long pursuit of justice, and finally to the trial itself.

Most notably, it spends long slabs of time with the sisters in the hotel where they stayed for the trial, able to support each other but not permitted to share details of their testimony. It captures the moment immediately after Erlich – who had written a book about her experiences – hears the full details of what happened to her sisters when they testify. And it captures the moment when Meyer hears that Leifer has been found not guilty on the charges relating to her abuse (while being found guilty of those relating to her sisters’ abuse).

It’s all incredibly intimate, up-close and raw. And it makes this most public case personal again.

For Meyer, the day of the verdict was complex.

“It was heartbreak. It was devastation,” she says. “Justice drove me for many years, and justice was denied.”

For months, she couldn’t speak about it, and for a while she thought she might never do so again. “And then I realised that ultimately, if I do that, I’m letting her win,” she says. “I felt she had won already by getting a not guilty verdict with my charges, and I thought I don’t want her to win, so I’m going to go out there and just start talking. And that’s what I did, and that really helped me to work on my healing.”

Remarkably, Meyer remains a member of the Adass community, where she advocates on behalf of abuse survivors. Erlich and Sapper left the community, but each in their own way have slowly found a way to connect with their Jewish heritage on a different basis.

In the wake of her experience, says Sapper, “I needed to throw away everything that I knew, and that included religion and Judaism. I didn’t engage with it for many years. But over the past five or six years, I’ve married and had kids, and my husband’s family is a traditional [non-Orthodox] Jewish family, and I’ve learned Judaism and religion are separate things. I enjoy the culture and traditions in their family, it’s a beautiful connection time, so I’ve started to engage with that and see it’s not mutually exclusive.”

Erlich similarly had a period in which she totally rejected all things Jewish. But now she’s working with Pathways, an organisation that offers support to members of insular Jewish communities who are having issues and don’t know where to turn.

“It’s not at all about dragging people away from religion,” she explains. “It’s very much ‘here’s a safe space for you to have those questions, to decide what’s right for you’. I’m enjoying using the skills we learned through all those campaign years to do something really positive and create change.”

The sisters’ experience was at once commonplace – someone in power recognised their vulnerability and mercilessly exploited it – and unusual – as members of a closed community that did nothing to educate its young women about sexual matters, they were uncommonly naive and isolated.

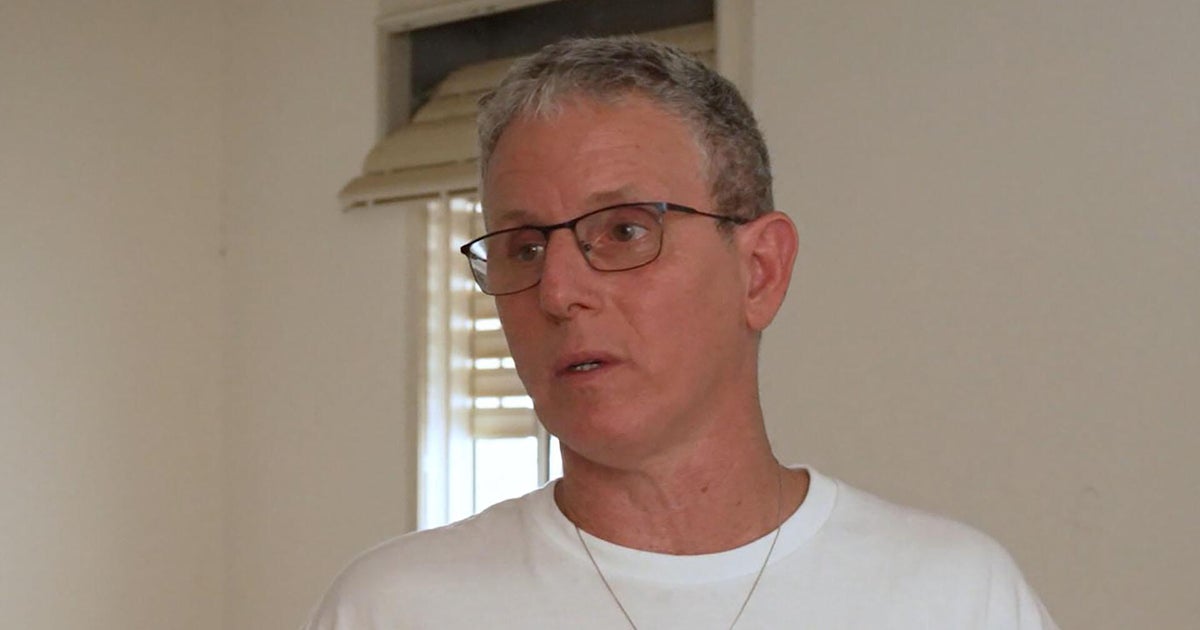

Nicole Meyer, Ellie Sapper and Dassi Erlich. The sisters’ story is one of endurance - and togetherness. Credit: Wayne Taylor

When they did recognise and report what had been done to them, it cost them enormously; they were suddenly cut off from the only community they had known, and thrust into a battle that would occupy years of their lives.

What got them through was the support of a few close allies (former premier Ted Baillieu in particular), and the fact they were doing it together.

“I think if any of us had been doing it alone, we would have not finished,” says Erlich.

“We’ve all given each other strength,” says Sapper. “If one of us is down, the others pull her up. We’ve just given each other that support all the years to get through it.”

“We would have burned out and crashed a lot earlier [if we’d done it solo],” says Meyer.

And if they had it all to do again?

“I’d do it, even if the result was the same, because of the accountability that perpetrators have when they’re put to the test,” says Meyer.

“Their name is there, they’re in court, they don’t know if they’re going to get guilty or not guilty. There’s a level of accountability in their community, in their family, regardless of whether you win it or not. It’s in their face.

“Any survivor who has the strength and support system to do so, go to the police, give your statement, and let’s get those perpetrators off the streets,” she implores. “I don’t regret it at all.”

* Revealed: Surviving Malka Leifer is on Stan from Sunday. Stan and this masthead are owned by Nine.