Jobe Watson walked out of the Court of Arbitration for Sport in November 2015 and knew what was coming wasn’t going to be good. He just didn’t know yet what bad meant.

Watson had gone to Sydney to give evidence in person before the CAS hearing into the Essendon Football Club’s 2012 supplements regime.

That night, Essendon chief executive Xavier Campbell called Watson to ask how his evidence had gone.

“Yeah, it was a very interesting experience,” Watson told Campbell. “But we’re f---ed.”

“What? What do you mean?” Campbell asked.

“I’m telling you, I can read a room. And we’re f---ed.”

“You can’t say that. How would you possibly know?”

“Xavier, I’m telling you.”

For Watson, it was the vibe. He sensed from the tone of the questioning and the tribunal’s demeanour that the sentiment was against Essendon. Going into the hearings he’d felt optimistic because the Essendon players had, in March 2015, been cleared by the AFL Anti-Doping Tribunal.

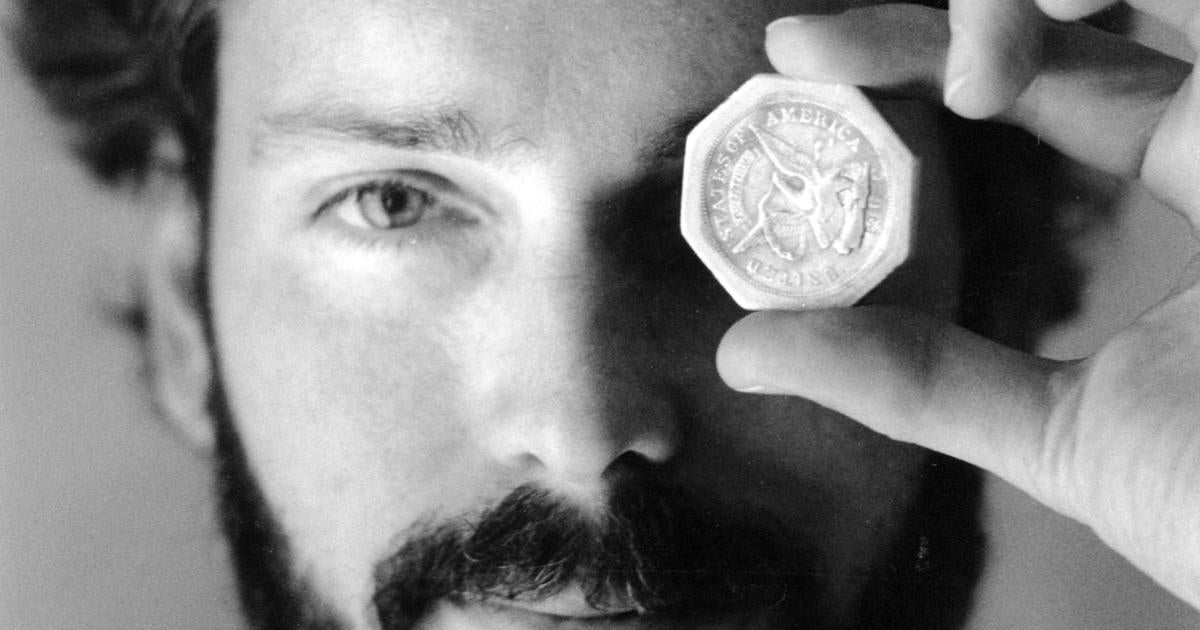

Former Essendon captain Jobe Watson now works in property. Credit: Domain

Watson sat through the next day or two of hearings in Sydney before returning to Melbourne and getting back into pre-season training, then breaking for Christmas.

On January 11, 2016, while the players were training at Tullamarine, word came through that the CAS had made its decision. It would be handed down the next day.

“I told a couple of players after the hearings that I thought we were in trouble, but you have no idea what, ‘This doesn’t look good for us’ means because it was unprecedented, and you’re not exposed to what a punishment might look like,” Watson said.

“I distinctly remember leaving the club the day before we were finding out the results on a Tuesday morning – which was the Monday afternoon in Switzerland – and I remember packing my bags and leaving, walking out of the club thinking, ‘I have no idea if I’m coming back here or not’.”

Essendon players, including Dyson Heppell (foreground), train on January 11, 2016, the day before their suspensions were announced.Credit: Pat Scala

Tuesday, January 12, 2016

The players

Amid the many important moments in the Essendon saga, this day must be regarded as one of the most significant in Australian sport. Never before had a team been wiped out through a lengthy suspension. A group of 34 players – they would come to be known as “the Essendon 34” , and 12 of them were still at the club at the time – were banned for the entire 2016 season. Ten years later, it remains one of the most dramatic days in Australian sport. Some say the Bombers are still to recover. Certainly, it informs much of the club’s on-field difficulties over the past decade.

Early on the morning of January 12, Michael Hibberd and Jake Melksham picked Watson up at his bayside house and the trio drove in silence to the Novotel in St Kilda. They made their way to the basement conference rooms where other players were gathering along with lawyer Tony Hargreaves, AFL Players Association CEO Paul Marsh and general counsel Brett Murphy.

Nearly a year earlier, on March 31, 2015, when the AFL Anti-Doping Tribunal decision was handed down, the affected players also met away from the club, at the Pullman Hotel.

The Essendon 34 front the media at the Pullman Hotel on March 31, 2015, the day the AFL Anti-Doping Tribunal delivered a “not guilty” finding. Credit: Getty Images

“The lawyers left the room and it was just silent,” Watson recalled. “We were just sitting there as a group waiting for them to come back. There’s so much tension and nervous energy there that no one spoke. No one was chatting, which is rare for a football group. There’s no jovial feel about the room at all, it was just dead silent.

“Then [Brett] Murphy and Tony Hargreaves, the lawyer, walked in and when they opened the door they were looking at the ground, and we were like, ‘Oh this is not good’. But still, at that point, you’re thinking, ‘What is not good? What does that mean?’

“You are not really even thinking about length of time of suspension or anything like that. I wasn’t thinking, ‘OK, not good equates to six months’. I was probably more like ‘not good’ is being found guilty.

“Then they deliver what ‘not good’ actually equates to. Everyone was trying to comprehend – what does this actually look and feel like? You hear the initial results, and then you’re not really tuned in because you are sort of hit by what those initial results are.

“Later you get a sense of what these details actually equate to but, in the moment, you just get hit by the sledgehammer. I just recall there were a lot of, like, vacant looks on people’s faces, and just a lot of fear. You know when you see fear on people. That’s what I recall most, it was just shock.”

A few players started to cry quietly, others sat staring blankly. The first to move was Dyson Heppell. Only a month earlier, he had been named vice captain of the club under Watson – now he was one of the banned players.

The Age’s front page on January 13, 2016.Credit: The Age

“The thing that stood out to me the most was because 34 blokes were getting this news, you don’t look at them all at once, but Dyson Heppell got up and walked around and started hugging every player,” Marsh remembered.

“There were a lot of grown men crying in the room, and that was the moment I just thought, ‘Geez, that is selfless leadership’. I’ll never forget Dyson doing that. He’s one of the youngest players in the room and I just think he saw his mates in complete devastation.”

The players milled around for a short time asking similar questions again and again, trying to get their heads around the news and what it meant. What could they do? Could they still go to games? Could they go to their kids’ footy? There was still a lot of grey area, Watson said. Eventually, they left the Novotel and went to David Myers’ place for breakfast, though no one felt much like eating.

“We were originally going to go back to my place, but then we knew there’d be media waiting outside my place, so it didn’t make sense to be there,” Watson said.

“It was shock for a period of time because it was just this rug got pulled out from under you. You’ve been cleared by one tribunal, you’ve done the bulk of training to get ready for a season, and then it just goes and evaporates in a moment.

“It’s difficult to be in the mindset of, ‘OK, well, what are the consequences of this’ when it’s such a big change to what your habits are overnight. It was made very clear straight away there was [to be] no communication [with the club].”

Watson was not shocked by the result, given his sense walking out of the CAS hearing, but that didn’t diminish his frustration.

“I felt like the evidence that was presented – and I read through every day of the first hearing of the AFL tribunal, you know – seemed to feel that there was no way that you could say that this person had this [substance] then, and there was no testing that produced any form of guilt in terms of positive tests,” he said.

“So it was very hard to say that this is when it [Thymosin Beta-4 or TB4] arrived, and this person had this then, and we can say for sure that that occurred. That was just not there, that evidence didn’t exist, and so I felt confident going into the CAS hearing.

“They [the World Anti-Doping Agency] could never identify who had what and when and so they just clumped us all together into one bag and said, ‘You’re all guilty’.”

Nonetheless, this line of defence – that WADA couldn’t be certain what the players took because the players themselves didn’t know and there were no records – was always going to be problematic. The WADA code operates under a strict liability that an athlete is responsible for what goes into their body.

Furthermore, WADA had argued it was incriminating, not just coincidental, that no player listed the injections, either TB-4 or any variation on thymosin, in their drug declaration forms when they were drug tested. Some players listed Panadol, but none mentioned the injections. WADA, and ultimately the CAS, felt this militated against the idea the players were sure the product they took was legal.

“Initially, I guess the results hit everyone the same, and it just filled you with uncertainty,” Watson said.

“I remember thinking, ‘Let’s just try and get through today and see what tomorrow looks like’. And it was like that for the first two weeks of it; just get through a day because all your planning has gone out the window.”

The AFL

Like the players, the AFL executive had arrived early at their headquarters at Etihad Stadium, as it was then known. They gathered in Gillon McLachlan’s office by 7am. Simon Lethlean, who was then head of broadcasting and fixturing, and Andrew Dillon, then the league’s general counsel, were with McLachlan, along with communications director Liz Lukin and Brett Clothier, who headed integrity (he left the AFL a year later to run the Athletes Integrity Unit for World Athletics, headquartered in Monaco).

Then-AFL chief executive Gillon McLachlan and then-chairman Mike Fitzpatrick on the day the bans came down.Credit: Eddie Jim

A guilty finding was not unexpected. Half a team missing a season was.

When the email dropped, and Dillon read it out, the mood in the room was at once angry and pragmatic. There was frustration and anger with the position Essendon had put their players in, and the impact on the wider competition. On the pragmatic side, the reality quickly set in that the decision represented a real threat to the season and, by extension, the code, if it endangered broadcasting and stadium deals. Of the 34 players banned, 12 were still Essendon players, five more were playing at other clubs and the remainder had retired or been delisted.

Without a dozen players, Essendon could not comfortably field a team for the year and the consequences and logistics of that were immediately front of mind. Where would top-up players be sourced from? What happened to the salary cap? What about the rules around short-term contracts and impacts on second-tier competition contracts? A team, any team, would satisfy the broadcast contract, as opposed to pleasing the broadcaster.

The pragmatic approach was predicated on an underlying acceptance, reinforced in the meeting, that this was the first and most important message to be conveyed in AFL executive’s public response, that these were details that would be worked through. They came a distant second to concerns for the health of the players involved. Put aside the fact the CAS decided a substance the players took, or were given, was performance-enhancing. Even without that, at the heart of Essendon’s defence was the unseemly fact that their players had been injected with substances and that no one could – or would – confidently identify who got what and when.

The health concerns were real. So, too, was the anger this caused at very senior levels of the AFL. The fact the club did not fully grasp its culpability in this and responded by fighting through myriad legal challenges, including an ultimately futile Federal Court appeal, mystified, frustrated and angered some on the AFL executive and commission. While the Bombers said they were seeking to protect the players’ innocence, some commissioners felt it only served as a second betrayal.

The club

For the second time, Xavier Campbell picked up the phone to an expletive that succinctly informed him of what was to come.

“You’re f---ed.”

Campbell had arrived at “the Hangar”, Essendon’s Tullamarine headquarters, early on January 12, 2016. Campbell, new club chairman Lindsay Tanner and the rest of the board gathered in the boardroom. Board member Paul Brasher (who went on to succeed Tanner in 2020) and former chair Paul Little, whose tenure had spanned years of the supplements saga that made them intimately involved in the case, were also there.

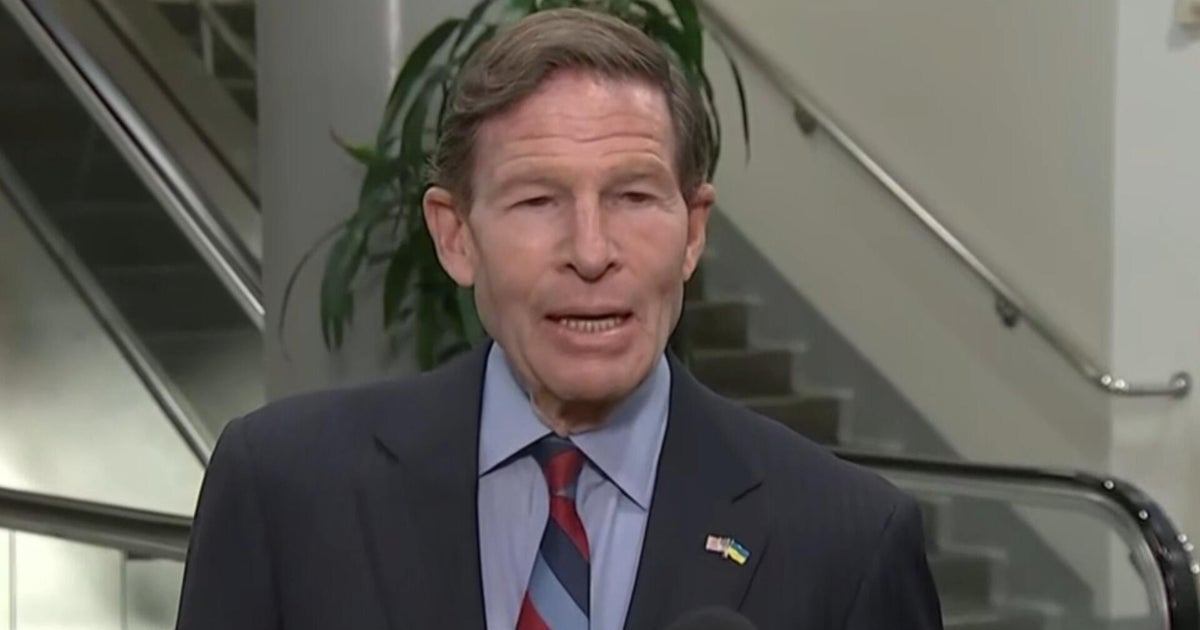

Xavier Campbell, Essendon’s then chief executive, at club headquarters on January 12, 2016. Credit: Darrian Traynor

Campbell’s phone went off. He left the boardroom to take the call.

“Mate, you are f---ed,” said the voice on the other end. It was a well-connected person whom Campbell declines to identify.

“It’s the worst of the worst-case scenarios. You are f---ed.”

Says Campbell: “I was sitting by myself in the office with the door closed, and it was just this overwhelming feeling. I reckon I sat there for five or six minutes by myself. I mean, we had done scenario planning, but this was, this was at the far right of any scenario plan we had thought about.

“I called Lindsay into my office and told him the news, and Lindsay (a former federal cabinet minister not unfamiliar with grave conversations) was as good a person as you could have during a period like that because he was incredibly calm and very pragmatic.

Then-Essendon president Lindsay Tanner.Credit: Getty Images

“We spoke about what we would need to do, that even though we had scenario planned, now that it was about to be real, and it was really bad, it was a different matter. We agreed to wait for the official decision to tell the rest of the board.”

When the news came, it came with a ding. An email dropped in Campbell’s inbox and he and Tanner read it first. A two-year ban, while backdated, still meant a season out of the game for the players. Campbell and Tanner walked into the boardroom and told the board.

“There was a degree of shell shock,” Tanner said.

“But to the great credit of the board members involved, everybody pretty quickly amped into, ‘We’ve got stuff to do here. We’ve got to work out how we’re going to publicly respond’.”

‘Suddenly it was just survival’

Downstairs at “the Hangar”, the remnants of the Essendon players not facing doping charges had gathered with John Worsfold, who was appointed senior coach in October 2015, and the other coaches and fitness staff. With so many players missing there were nearly as many staffers as players.

Campbell and the head of HR, Lisa Lawry, along with Tanner, walked down to deliver the news.

“We’re down 12 players on our list ... The rest of them were looking at each other [saying], ‘What are we training for?’”

John Worsfold, Essendon’s then coach, recalls the aftermath of the players’ suspensionsThese were the so-called “unaffected players”. They were utterly affected.

“That was a very hard discussion because clearly there was an impact on the affected players, of course the impact on them and their families was the most significant. But what happened here was that it became very real that you’ve just lost this whole group of teammates,” Campbell said.

“John had come in as someone [who] was going to lead a team out of it and make football fun again, and suddenly it was just survival.”

John Worsfold, Essendon’s then coach, speaks to the media in the days after the players were suspended.Credit: Wayne Taylor

Worsfold hadn’t countenanced a suspension of this magnitude. He’d been drawn to Essendon after watching the drained faces of Watson and others during the year, thinking these players should be enjoying the greatest years of their life. Football was supposed to be fun, and they looked like hell. He assumed that having been successful in the AFL Anti-Doping Tribunal, a guilty finding at CAS would, at worst, bring a modest suspension. He was wrong.

“When it happened, we had to communicate to the playing group basically, ‘This has happened, we will work out how we’re going to deal with it, but we need to support you guys and help you understand what’s happened, and we will get through this’,” Worsfold said.

Loading

“Sheeds [Kevin Sheedy] was around at the club and I asked him if he’d come down and address the players as well because of his standing at the footy club. Lindsay also spoke to the players.”

Some of the non-suspended players joined Watson and the 34 at Myers’ house. “[There was] a bit of mourning or grief, [and] just to get together and try and understand what’s happening,” Worsfold said.

Then the coach got down to business. “Around what does it mean for us? Now we’re down 12 players on our list ... The rest of them were looking at each other [saying], ‘What are we training for? We don’t even know if we’re going to be able to play in the season’. We were trying to reassure them that we’ll still be fielding a team. The season is going to go ahead.”

Keep up to date with the best AFL coverage in the country. Sign up for the Real Footy newsletter.