Opinion

December 8, 2025 — 12.00am

December 8, 2025 — 12.00am

The recent message from financial markets to mortgage customers has been pretty clear: don’t expect further cuts in your home loan interest rate.

That story is likely to be reinforced on Tuesday when the Reserve Bank, led by governor Michele Bullock, holds its final board meeting of the year. Investors are nearly certain the cash rate won’t change, and many RBA-watchers are betting rates will stay unchanged for a while yet – perhaps even all of next year.

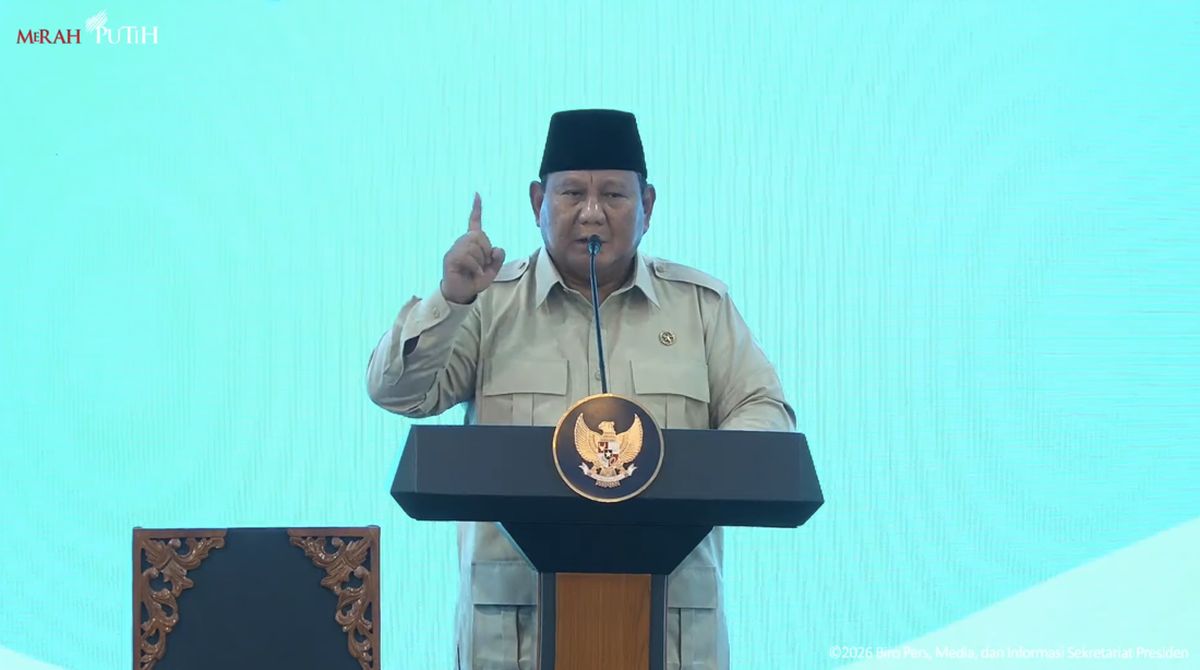

Reserve Bank governor Michele Bullock is unlikely to start slashing rates again any time soon.Credit: Louie Douvis

Who knows if they are right – even the Reserve Bank can’t be sure of exactly where interest rates might move from one board meeting to the next.

But if you step back from trying guess what the RBA might do at this meeting or the next, you can be more confident about a longer term trend: barring a crisis, we are not about to return to the era of very low interest rates of late last decade, let alone the zero-rate world that arrived thanks to COVID-19.

For those who’ve forgotten, the second half of the 2010s and the early years of the 2020s was a time of very cheap debt. The cash rate spent years under 2 per cent, falling to less than 1 per cent by 2019. Then borrowing got even cheaper when the COVID-19 emergency of 2020 stoked fears of a great depression, taking rates to near zero.

There are a few reasons why we’re probably not returning to an era of such cheap money. But one that’s getting a lot of attention from economists right now is the worry that our economy is running at close to its “capacity”, meaning there’s less scope for rate cuts.

Loading

When economists talk about an economy’s “spare capacity”, they are basically referring to the ability of firms to access the labour and capital needed to meet demand. If there’s not enough capacity, such as a shortage of skilled staff, it sparks inflation as firms compete for available workers. Too much capacity, on the other hand, causes low inflation.

Given that central banks such as the Reserve Bank move interest rates to target inflation, the level of spare capacity in an economy is a big deal. It matters a lot for interest rates.

A high amount of “excess capacity” was a big reason why interest rates were so low during the late 2010s. Unemployment was higher, typically above 5 per cent, unlike today, when it is 4.3 per cent. The RBA’s key problem was that inflation was lower than its 2 to 3 per cent target range, so it tried to boost economic activity and inflation by using its main weapon – lowering the cash rate.

From this level of already low rates, the pandemic forced central bankers around the world to go all out to prevent a complete meltdown. Rates tumbled even lower. Once the crisis receded and inflation reared its head, interest rates couldn’t stay at emergency lows, so central banks reached for that weapon again. The RBA raised rates by 4 percentage points from 2022, before starting a cutting cycle at the start of this year.

Fast-forward to today, and many think this cycle of rate cuts has ended after only three 0.25 percentage point reductions. Indeed, some economists are even talking about rate hikes. Why has the RBA been forced to quickly move from rate-cutting mode to potentially thinking about increases?

The obvious reason is the recent jump in inflation. The bigger concern is that this has happened because the economy is hitting those dreaded “capacity constraints”.

As CBA chief economist Luke Yeaman said in a recent note, the economy is starting to pick up and there is less spare capacity than during previous economic cycles.

Loading

Rather than having unemployment above 5 per cent, as we did for much of the 2010s, it is now lower, at 4.3 per cent. It’s good news that more people are in work, but it also means it is easier to hit those capacity constraints, causing inflation. It also means relatively small cuts in the cash rate can risk sparking inflation. “The RBA will need to remain ‘on alert’ to this risk, meaning interest rates can’t fall as far, and rates will need to stay higher than in past cycles,” Yeaman said.

What is more, this worry about a lack of capacity isn’t the only reason to think we are not going back to the cheap money era.

A second, more global reason to think that that world is behind us is an economic concept called the “neutral interest rate”. This is essentially the interest rate level that neither stimulates nor slows economic growth.

The “neutral rate” is a bit of a slippery concept: we don’t know exactly what that number is. But the important point is that economists thought the neutral rate was falling for decades, and then more recently, it has been rising.

Why might that be? In the long term, economists think global interest rates are determined by the balance between savings and investment: more saving will drag down rates, while more investment will push them up.

One theory for the very low rates of the 2010s was the high amount of saving by an ageing population alongside a lack of investment, for example.

More recently, however, economists have been pointing to big global forces that would drive up the “neutral” rate, such as rising investment.

RBA assistant governor Christopher Kent in October said estimates of Australia’s neutral rate had risen by about 1 percentage point.

Kent said reasons for this increase in neutral rate estimates could include “rising global public debt, lower saving by retiring Baby Boomers, and increased public and private investment, including in the green energy transition.”

Loading

Other mega-trends (not named by Kent) that are boosting investment around the world are the rush to build data centres, higher defence spending by governments and the increase in companies “on-shoring” or expanding domestic production. If all that investment causes a change in the balance between saving and investment, it could nudge up interest rates further.

To be fair, these are trends that play out over many years, so they’re not going to affect short-term interest rate moves. But over the longer term, economists think our neutral rate has gone up, and that suggests the actual cash rate set by the RBA will also need to be higher to have the same impact.

The bottom line for borrowers is this: unless there’s some sort of economic emergency, don’t expect interest rates to return to the rock-bottom levels of late last decade.

The Business Briefing newsletter delivers major stories, exclusive coverage and expert opinion. Sign up to get it every weekday morning.

Most Viewed in Business

Loading