Paul AdamsBBC diplomatic correspondent

PM: UK will recognise Palestinian state unless conditions met

The UK, Australia and Canada have recognised a Palestinian state, while France and other countries are set to do so in the coming days.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu earlier warned the decisions would "Hamas's monstrous terrorism". The US has also voiced strong opposition to the move.

What will recognition mean, and what difference would it make?

What does recognising a Palestinian state mean?

Palestine is a state that does and does not exist.

It has a large degree of international recognition, diplomatic missions abroad and teams that compete in sporting competitions, including the Olympics.

But due to the Palestinians' long-running dispute with Israel, it has no internationally agreed boundaries, no capital and no army. Due to Israel's military occupation in the West Bank, the Palestinian authority, set up in the wake of peace agreements in the 1990s, is not in full control of its land or people. Gaza, where Israel is also the occupying power, is in the midst of a devastating war.

Given its status as a kind of quasi-state, recognition is inevitably somewhat symbolic. It will represent a strong moral and political statement but change little on the ground.

But the symbolism is strong. As the former UK foreign secretary David Lammy pointed out during a speech at the UN in July: "Britain bears a special burden of responsibility to support the two-state solution."

Bettmann via Getty Images

Bettmann via Getty Images

British troops lower the Union Flag to officially end British rule in Palestine in 1948

He went on to cite the 1917 Balfour Declaration - signed by his predecessor as foreign secretary Arthur Balfour - which first expressed Britain's support for "the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people".

But that declaration, Lammy said, came with a solemn promise "that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine".

Supporters of Israel have often pointed out that Lord Balfour did not refer explicitly to the Palestinians or say anything about their national rights.

But the territory previously known as Palestine, which Britain ruled through a League of Nations mandate from 1922 to 1948, has long been regarded as unfinished international business.

Israel came into being in 1948, but efforts to create a parallel state of Palestine have foundered, for a multitude of reasons.

As Lammy said, politicians "have become accustomed to uttering the words 'a two-state solution'".

The phrase refers to the creation of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, broadly along the lines that existed prior to the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, with East Jerusalem – occupied by Israel since that war - as its capital.

But international efforts to bring about a two-state solution have come to nothing and Israel's colonisation of large parts of the West Bank, illegal under international law, has turned the concept into a largely empty slogan.

Who recognises Palestine as a state?

Palestine is currently recognised by around 75% of the UN's 193 member states.

At the UN, it has the status of a "permanent observer state", allowing participation but no voting rights.

With the British and French recognition, Palestine will soon enjoy the support of four of the UN Security Council's five permanent members.

China and Russia both recognised Palestine in 1988.

This will leave the US, Israel's strongest ally by far, in a minority of one.

Washington has recognised the Palestinian Authority, currently headed by Mahmoud Abbas, since its formation in the mid-1990s.

Since then, several presidents have expressed their support for the eventual creation of a Palestinian state. But Donald Trump is not one of them. Under his two administrations, US policy has leaned heavily in favour of Israel.

Why are the UK and other countries doing it now?

Successive British governments have talked about recognising a Palestinian state, but only as part of a peace process, ideally in conjunction with other Western allies and "at the moment of maximum impact".

To do it simply as a gesture, the governments believed, would be a mistake. It might make people feel virtuous, but it would not actually change anything on the ground.

But events have clearly forced the hands of several governments.

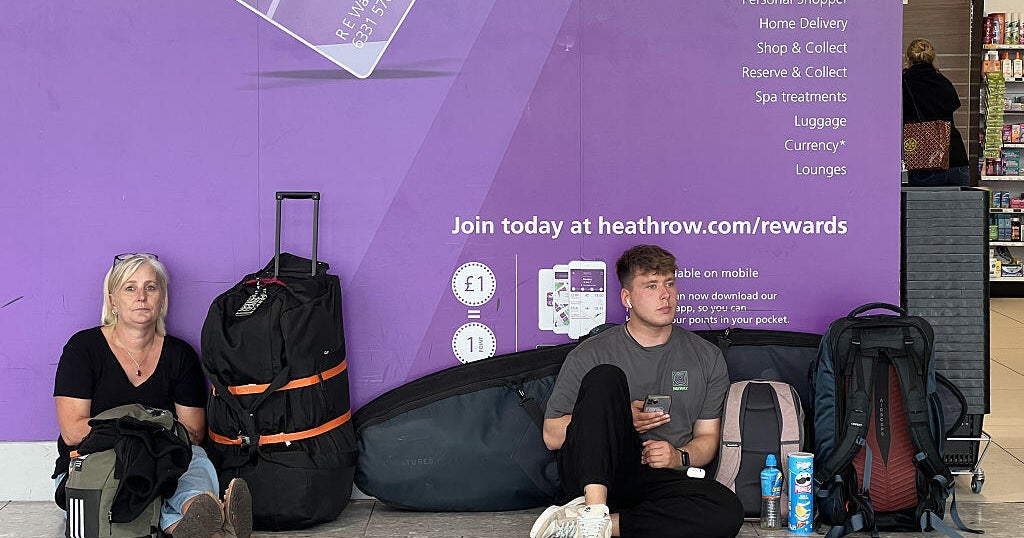

The scenes of creeping starvation in Gaza, mounting anger over Israel's military campaign and major shifts in public opinion – all have played a role in bringing us to this point.

Reuters

Reuters

The "worst-case scenario of famine is currently playing out" in the Gaza Strip, UN-backed global food security experts warn

The US is opposed

The Trump administration has never made any secret of its opposition to recognition, with the US president himself acknowledging he has a "disagreement with the prime minister on that score" at a joint press conference on Thursday.

The two leaders did say they discussed the issue though during their one to one meeting.

In fact, it's clear that the US position has hardened into outright opposition to the very concept of Palestinian independence.

In June, the current US ambassador to Israel, Mike Huckabee, said he thought the US no longer supported the creation of a Palestinian state.

More recently, the US Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, has said that Hamas would "feel more emboldened" by the international push to recognise Palestine.

His words, during a joint news conference with Netanyahu on 15 September, echoed the Israeli argument that recognition is a "reward for terrorism," following the devastating Hamas attacks of 7 October 2023.

Rubio also says the US has warned those advocating recognition that it's likely to provoke Israel into annexing the West Bank.

"We told them that it would lead to these sorts of reciprocal actions and that it would make a ceasefire [in Gaza] harder," he told reporters at the beginning of September.

2 hours ago

1

2 hours ago

1