Australia’s food and beverage legislation is failing to protect children from a bombardment of unhealthy, inexpensive and aggressively marketed products, the United Nations’ agency for children has warned, as obesity overtakes thinness as the most globally prevalent form of malnutrition for the first time in recorded history.

UNICEF urged the Australian government to overhaul food labelling requirements, clamp down on junk food advertising, and safeguard against political interference from the ultra-processed food industry, estimating in a report released on Wednesday that one-third of Australians aged five to 19 now have a body-mass index (BMI) within the obese or overweight range.

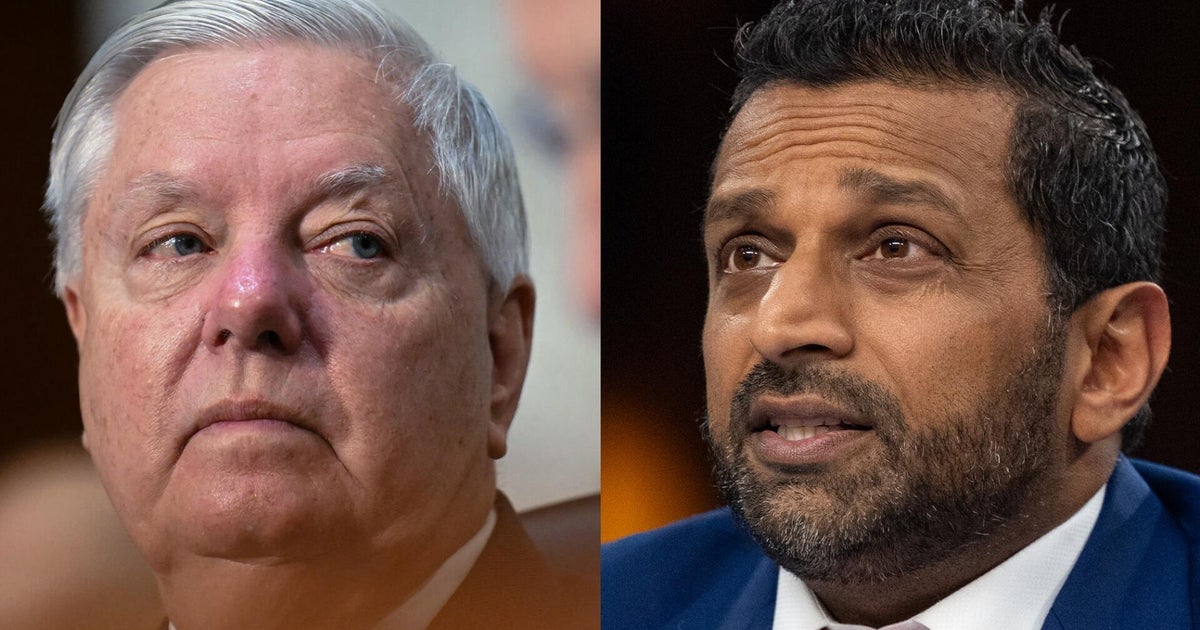

Obesity has overtaken thinness as the most prevalent form of malnutrition for the first time in recorded history, a global nutrition report released by UNICEF found.Credit: Aresna Villanueva

“Australia, along with governments across the world, must look to implement comprehensive mandatory policies to improve children’s food environments, including food labelling, food marketing restrictions, and food taxes and subsidies,” said UNICEF Australia head of policy Katie Maskiell.

For decades, global efforts to combat child malnutrition have largely focused on those going hungry. But the report says obesity is now the most prevalent form of malnutrition in all regions excepts sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, rising from 3 per cent in 2000 to 9.4 per cent in 2025.

The estimated proportion of children considered underweight has fallen from 13 to 9.2 per cent in the same 25-year period.

In Australia, the report estimated about 19 per cent of five to 19-year-olds have a BMI within the obese range, while 36.3 per cent are considered overweight – well above the global average of 19.8 per cent.

UNICEF’s estimates are higher than those used by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, which have sat relatively stable at about 25 per cent for two- to seven- year-olds in the last 15 years.

Professor Louise Baur, a child and adolescent health expert at the University of Sydney and former president of the World Obesity Collective, said successive governments have failed to address the surge in obesity rates coinciding with the advent of ultra-processed foods and computer gaming in the mid-80s.

She said tackling obesity and unhealthy eating was not about individual or parental choices, but governments protecting children from sophisticated marketing, boosting access to green spaces, and making healthier food more affordable.

“It’s a manifest failure to keep on saying, ‘eat less, exercise more’,” she said. “It’s a profoundly stupid way to think … because the forces promoting passive overconsumption of food and sedentary behaviours are immense.”

Professor Louise Baur, former president of the World Obesity Federation, said successive governments had failed to tackle the causes of rising obesity rates. Credit: James Brickwood

A parliamentary inquiry into Australia’s diabetes epidemic last year suggested taxing unhealthy drinks based on their sugar content, and urged Prime Minister Anthony Albanese to consider restricting the advertising of unhealthy food to children under 16 on television, online and on gaming platforms.

The government is yet to respond to the inquiry’s recommendations.

Loading

Australian Bureau of Statistics survey data released last week showed Australians are consuming lower volumes of sugary drinks but more snack foods than a decade ago, while consumption of fruit has decreased by 17 per cent.

The UNICEF report found ultra-processed foods – products made in factories containing little to no whole foods – now account for at least half of the total energy intake in Australia, Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom.

“These levels are so high that they match the description of a staple food – meaning they constitute a dominant portion of adolescents’ diets,” it said.

Dr Paul Hotton, a Sydney-based community child health paediatrician, said conditions such as type 2 diabetes, sleep apnoea, and cardiovascular issues were appearing much earlier in his patients as a result of unhealthy eating, increased screen time, and reduced exercise.

Loading

“We’re seeing greater prevalence of academic issues, cognitive issues, sleep issues, which then transition … into later adult life,” said Hotton, who is president-elect of the paediatric and child health division of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians. “We see it as a health issue that’s going to have really significant financial impact for Australia in 15 or 20 years when those children become adults needing treatment to manage their chronic illnesses.”

UNICEF estimates that, by 2030, the obesity and overweight crisis will cost the Australian economy $66 billion every year. The global economic impact could exceed $US4 trillion ($6 trillion) if current trends continue, the report warned.

Australia’s neighbours in the Pacific have some of the highest rates of obesity and overweight in the world: almost two-thirds (62 per cent) of five to19 year olds in the Cook Islands; 56 per cent in Tonga; and 49.6 per cent in Samoa.

Millions of children across the world remain underweight and at risk of starvation.

Most Viewed in National

Loading