AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images

Indian cities generate millions of tonnes of rubbish every year, but waste disposal systems are inadequate

"Want the royal charm of Jaipur? Don't come here, just buy a postcard," a local taxi driver quipped during my recent visit to the north-western Indian city.

I had asked him why Rajasthan's amber-hued capital - thriving with tourists drawn to its opulent palaces and majestic forts - looked so ramshackle.

His answer reflected a resigned hopelessness about the urban decay that plagues not just Jaipur but many Indian cities: choked with traffic, shrouded in foul air, littered with heaps of uncleared rubbish, and indifferent to the remnants of their glorious heritage.

In Jaipur, you will find the most sublime examples of centuries-old architecture defaced by tobacco stains and jostling for space with a car mechanic's workshop.

This raises a question: why are Indian cities becoming increasingly unliveable, even as hundreds of billions are spent on a national facelift?

India's rapid growth, despite high tariffs, weak private spending, and stagnant manufacturing, has been driven largely by the Modi government's focus on state-funded infrastructure upgrades.

Over the past few years, India has built shiny airports, multi-lane national highways and metro train networks. And yet, many of its cities rank at the bottom of liveability indexes. Over the past year, frustrations have reached a boiling point.

In Bengaluru - often called India's Silicon Valley for its many IT companies and start-up headquarters - there were public outbursts from citizens and billionaire entrepreneurs alike, fed up with its traffic snarls and garbage piles.

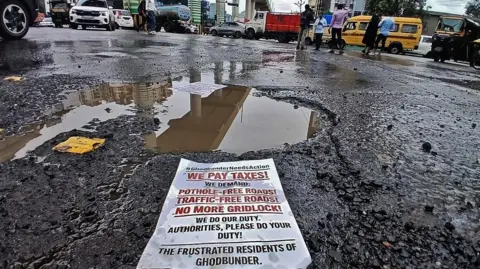

In Mumbai, the financial capital, citizens staged a rare protest against worsening pothole problem, as clogged sewage lines dumped garbage onto flooded roads during the extended monsoon.

In Delhi's annual winter of discontent, toxic smog left children and the elderly gasping, with doctors advising some to leave the city. Even footballer Lionel Messi's visit this month was overshadowed by fans chanting against the capital's poor air quality.

Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Residents of Thane near Mumbai staged a protest over potholes and traffic congestion in September

So why, unlike China during its boom years, isn't India's blazing GDP growth leading to a regeneration of its decrepit cities?

For instance, why is Mumbai - which publicly harboured dreams of becoming another Shanghai in the 1990s - unable to realise that ambition?

"The root cause is historical - our cities don't have a credible governance model," Vinayak Chatterjee, a veteran infrastructure expert, told the BBC.

"When India's constitution was written, it spoke of the devolution of power to the central and state governments - but it did not imagine that our cities would grow to become so massive that they would need a separate governance structure," he says.

The World Bank estimates that over half a billion Indians, or nearly 40% of the country's population, now live in urban areas - a staggering rise from 1960 when merely 70 million Indians lived in cities.

An attempt was made in 1992 to "finally allow cities to take charge of their own destinies" through the 74th amendment of the Constitution. Local bodies were granted constitutional status and urban governance was decentralised - but many of the provisions have never been fully implemented, says Mr Chatterjee.

"Vested interests don't allow bureaucrats and the higher levels of government to devolve power and empower local bodies."

This is quite unlike China where city mayors wield substantial executive powers controlling urban planning, infrastructure and even investment approvals.

China follows a highly centralised planning model, but local governments have freedom of implementation and are centrally monitored, with rewards and penalties, says Ramanath Jha, Distinguished Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation think tank.

"There are strong national mandates in terms of direction and physical targets that cities are tasked to achieve," Mr Jha writes.

Mayors of China's major cities have powerful patrons in the Communist Party's top committee and strong performance incentives, making these posts "important stepping stones for further promotions", according to Brookings Institution.

"How many names of mayors of major Indian cities do we even know?" asks Mr Chatterjee.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images

Toxic air is a recurring problem in Delhi, especially during winters

Ankur Bisen, author of Wasted, a book about the history of India's sanitation issues, says that mayors and local councils that run Indian cities are "the weakest organs of the state, closest to the citizenry, but tasked with the toughest problems to solve".

"They are absolutely emaciated - and have limited powers to raise revenue, appoint people, allocate funds. Instead, it is the chief ministers of the states who act like super mayors and call the shots."

There have been exceptional cases - like Surat city after the plague in the 1990s, or Indore in Madhya Pradesh state - where bureaucrats, empowered by the political class, have made transformative changes.

"But these were exceptions to the rule - relying on individual brilliance rather than a system that will function even after the bureaucrat is long gone," says Mr Bisen.

Beyond fractured governance, India faces deeper challenges. Its last census, over 15 years ago, recorded 30% urban population. Informally, nearly half the country is now thought to have taken on an urban character, with the next census delayed until 2026.

"But how do you even begin to solve a problem if you don't have data on the extent and nature of urbanisation?" asks Mr Bisen.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty Images

Bengaluru city is infamous for its traffic snarls

The data vacuum, and the non-implementation of the frameworks to transform Indian cities, well-articulated in the 74th constitutional amendment, reflect a weakening of India's grassroots democracy, experts say.

"It is strange that there is no outcry about our cities, like there was against corruption a few years ago," said Mr Chatterjee.

India will have to go through a natural "cycle of realisation", says Mr Bisen, giving the example of the Great Stink in London in 1858 which prompted the government to construct a new sewerage system for the city and marked the end of significant cholera outbreaks.

"It's usually [during] events like these when things reach a boiling point, that issues gain political currency."

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, X and Facebook.

2 months ago

16

2 months ago

16