Opinion

December 10, 2025 — 5.00am

December 10, 2025 — 5.00am

Six months into his second term as prime minister, Anthony Albanese’s government is entrenching its own reputation for political timidity, with the latest evidence tabled by Home Affairs officials in estimates last week.

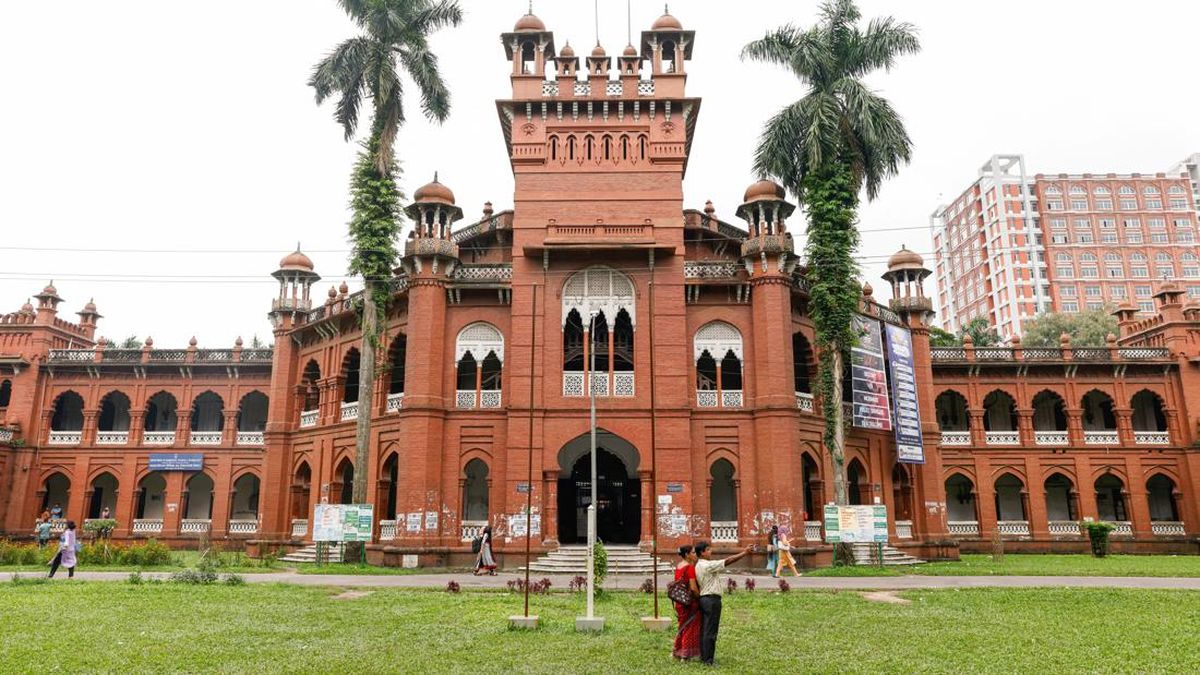

The subject of the documents was the 37 Australian citizens, the wives and children of former Islamic State fighters who have been stuck for six years in detention camps in Syria, and the revelation they contained was that Australia had been presented with a safe way to get them back.

“I want to go home and to school”: Maysa (left) at age nine with family members in al-Hawl camp in Syria in 2019.Credit: Kate Geraghty

To be clear, most Australians have little sympathy for these people and no desire to have them home. They participated in one of the most bloodthirsty, lawless and morally appalling religious-political movements we’ve seen. “They made their bed, they should lie in it,” people say.

Against that, their families and activists, including the charity Save the Children, have been agitating for their return. In the real world, of course, that will eventually happen. Nobody believes they will stay in Syria forever.

More than that, there are good reasons for an Australian government to bite the bullet and bring them home. Firstly, like it or not, these people are Australian citizens – born here, raised here, educated here. This makes them our problem, however long they spent in the so-called caliphate.

Secondly, the Syrian Kurds who run the camps have the right to be rid of them. The Kurds lost loved ones fighting IS and don’t even enjoy a sovereign state of their own. Leaving them to clean up our mess is the act of a bad and irresponsible global citizen.

Children play among the rocks in the foreign annex of al-Hawl camp in Syria in 2019.Credit: Kate Geraghty

Thirdly, we have functioning police and justice systems. If these women have committed crimes, then arrest them and put them on trial. Until then, our citizens are being indefinitely detained without charge or legal rights in a foreign land. In any other circumstances, this would be the subject of high-level diplomatic protest.

Finally, the longer they – and more pertinently their children – live in these conditions, the more likely they are to be traumatised and re-radicalised.

I can’t be more eloquent on this point than US military commander Admiral Brad Cooper, who said after a recent visit to a Syrian camp that he “saw first-hand the need to accelerate repatriations”. “Repatriating vulnerable populations before they are radicalised is ... a decisive blow against ISIS’ ability to regenerate,” Cooper said. ASIO made a similar point to the then-Coalition government in 2020.

Loading

In Australia, both flavours of politician have insisted they cannot act because it’s too dangerous to send public servants into Syria – an excuse looking increasingly threadbare since the overthrow of the Assad regime in December 2024.

Even if that level of risk still applied, there is an easy fix. The documents released in parliament this week reveal that the Americans have offered to do the hard work for us – to send in their specialists to extract the families safely. The only impediment is that the women and children don’t have Australian passports – a little administrative hurdle the government could surely clear if it had the will.

But it does not. This, too, is revealed in the documents. In notes of a meeting between activists and Home Affairs Minister Tony Burke in Punchbowl (in his electorate of Watson) in August last year – 10 months before the May election – the minister is noted saying: “Politics harder at this end of term.”

Burke comes across in the notes as somewhat sympathetic to the activists. But he urges them not to even discuss the issue publicly, lest his own government be scared back into its shell. “Public pressure makes it harder,” the notes quote him saying. “Don’t want govt to rule it out.”

That was before the election, though. Surely after Albanese’s crushing victory over immigration hardman Peter Dutton in May, the political calculus changed?

On election night, Anthony Albanese said “kindness” would guide how his government dealt with people in need.Credit: Alex Ellinghausen.

Apparently not. In September, six women and children found their own way out of al-Hawl camp using people smugglers. In the face of accusations of complicity from the opposition and some media outlets, Burke and Albanese contorted themselves into knots, insisting they’d had no hand in it. But if the women somehow made it to an Australian embassy themselves, the government was legally obliged to issue them passports.

I remember well when Labor under Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard were all about “smashing the people smugglers’ business model”. Now people smuggling is Labor’s model.

So, are there good reasons for this political faintheartedness? Would the electorate punish Albanese for returning these women and children?

The evidence suggests not. The Morrison government brought back eight orphans and one newborn baby in 2019 without murmur. In October 2022 – early in Albanese’s first term – four Australian women and their 13 children were brought back under former home affairs minister Clare O’Neil.

Loading

This indeed prompted a backlash. The government had a few rugged days on Sydney talkback and some quickly mollified pushback from local mayors. Independent MP Dai Le claimed the people of Western Sydney had been “offended”. That was about it.

The women faced charges of entering a declared area. None has been convicted. They live with their families under the eye of security officials, getting treatment and support. Nobody has come to harm. Those close to the families tell me the children are doing well.

When I talked to the women in the Syrian camp in 2019, their most fervent desire was, quite simply, to live a quiet and trauma-free life in their home country.

A strong government, a government confident of its ability to persuade, could handle the brief storm their repatriation would cause.

But of this government, which is now habituated to jumping at shadows, even that seems too much to ask.

Michael Bachelard is a senior writer and former foreign correspondent, deputy editor and investigations editor of The Age.

The Opinion newsletter is a weekly wrap of views that will challenge, champion and inform your own. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

Loading