This story is a part of our series exploring the benefits and cost of vitamins to our health and hip pocket.

See all 6 stories.Humans have always intuitively understood that certain foods contained health-altering properties. And what intuition was unable to make sense of, imagination filled the void.

Plato preached the virtues of moderation and variety in one’s diet, while Hippocrates intuited that we all had an individual response to foods, and that certain substances within foods could treat disease.

There is still a lot experts don’t know about vitamins.Credit: Aresna Villanueva

Yet, the ancient Greeks and Romans also believed that if it was not angry gods taking out their wrath on our mortal bodies, then the cause of disease was an imbalance of wet and dry, hot and cold in the body. The logic went that consuming foods considered wet or dry, hot or cold could restore that balance. Hence, “Let food be thy medicine”.

They thought that eating lettuce at night could cure insomnia (by cooling a person down) and that cabbage was a superfood that could fix most, if not all ailments (so much so, many swore by the humble veg: “So help me Cabbage”).

These weren’t the only imaginative ideas they had about food, which also included the medicinal seasoning of your dinner with fish-guts sauce; avoiding eating too many figs lest they cause head-lice; and treating snake bites by instructing the person treating the victim to suck the venom on a full stomach of garlic and nuts (before covering the bite with feathers plucked from the anus of a rooster or a chicken).

We’ve come a long way.

Science has cleared up much confusion, including what those helpful substances within foods are (vitamins) and how certain diseases could be caused and remedied by them. But, modern nutrition science remains relatively young, with the first vitamin (B) isolated in 1926, less than 100 years ago.

It was a vital step for understanding the role of micronutrients and treating deficiency diseases. In the decades afterwards strides were made in both knowledge and the chemical synthesis of vitamins and minerals.

But, it also led to an era where more emphasis was placed on the nutrient than the whole food.

As technology drove advances in food processing, a new type of product began flooding supermarket shelves: low-cost, highly processed foods fortified with minerals and vitamins.

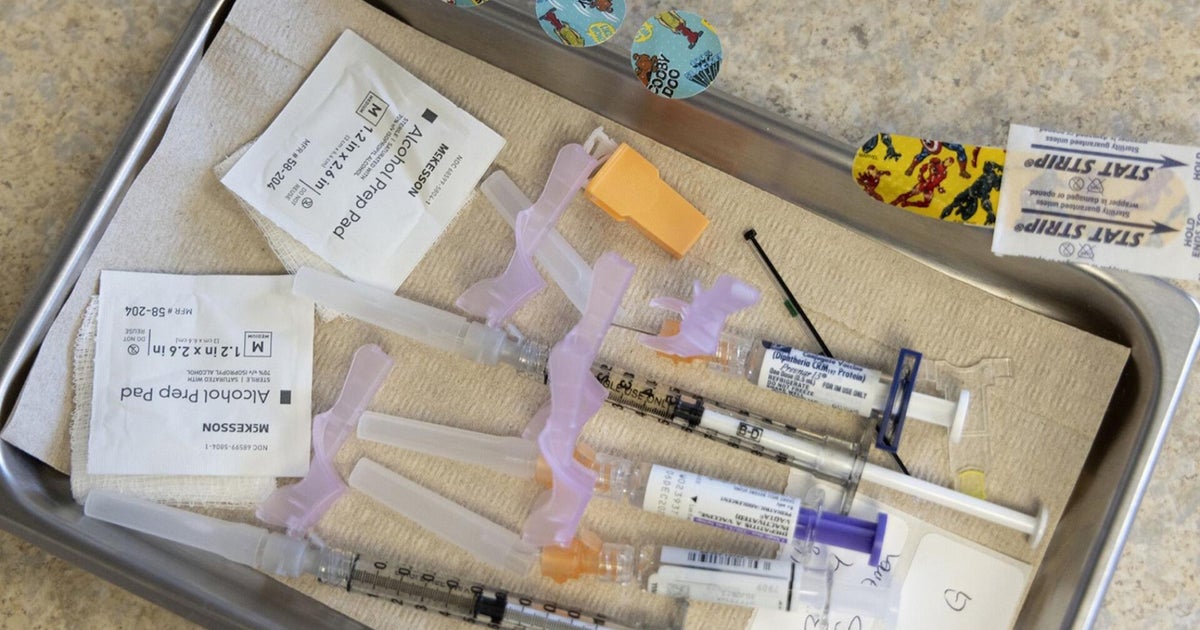

Fortified foods solved one problem, but in some instances created another. Credit: Getty Images

While specific nutrient deficiencies and related diseases plummeted, other diet-related chronic diseases began to soar, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, and some cancers.

Today, the pendulum has swung back and experts understand that it isn’t just about the macronutrients (fat, carbohydrate, protein, fibre, water) or micronutrients (the 13 essential vitamins as well as minerals such as magnesium, sodium and calcium).

Equally important is the matrix of the whole food and the interaction between the carbohydrate quality (eg, glycaemic index, fibre content), fatty acid profiles, protein types, micronutrients, phytochemicals, food structure, preparation and processing methods, and additives.

“There are a whole lot of other nutrients in foods that people have evolved on and yet, they think they can replace it with just one nutrient,” says Evangeline Mantzioris, program director of Nutrition and Food Sciences at the University of South Australia.

“There are a whole lot of other nutrients in foods that people have evolved on and yet, they think they can replace it with just one nutrient.”

Evangeline Mantzioris, program director of Nutrition and Food Sciences at the University of South AustraliaIn the 1980s and 1990s, when it was discovered that people who consumed lots of fruit and vegetables had lower rates of cancer, it drove an obsession with antioxidants.

“Everyone got excited and went ‘OK, let’s give everyone antioxidants in capsule form’,” Mantzioris says.

That was until one seminal study of people with lung cancer or those exposed to asbestos found those given antioxidant supplementation, in the form of vitamins A and E, were more likely to die.

“No one expected it,” she says. “It was rational – fruit and veg are good, let’s give it to them in a pill. But in a concentrated form outside of food, nutrients act differently.”

In the past 100 years, nearly half a million studies have been done on vitamins. We now have a lot of science to support (or challenge) our intuition. Yet, the imaginative claims continue. No matter how convincing vitamin brands and wellness influencers are with their claims, there are still significant gaps in knowledge.

“There’s a surprisingly large amount that’s not yet known about vitamins,” says Kamal Patel, a nutrition researcher and co-founder of Examine.com, the Internet’s largest database of nutrition and supplement research.

What is it that the experts still don’t understand?

There are still pieces of the nutrition puzzle that experts are trying to figure out.Credit: Getty Images

If a little is good, then more must be really good

Vitamins are essential for health and survival and have their origins in nature, giving them a health halo that medicines typically don’t enjoy. We also don’t require a prescription to buy them.

“People often assume there is no risk in taking vitamins and that if a little is good, then more must be really good,” says Oliver Jones, a professor of chemistry at Melbourne’s RMIT University. “This is not true.”

Research has tended to look at the minimum amounts of micronutrients we need to survive and to sustain basic health, explains Patel.

“However, the amount needed to optimise health or to address various health conditions, especially ones outside the most common ones, is not as well known.”

How much is enough or too much remains unanswered, as does the effect of our individual differences and lifestyles on those thresholds.

“Factors like genetics, gut microbiome composition, health status, and even time of day may influence how someone absorbs or metabolises a supplement,” says accredited dietitian and nutrition researcher, Danielle Shine.

The current guidelines do not account for that variability, says dietitian and nutrition research scientist, Dr Tim Crowe: “Two people could take the same dose of a vitamin and have radically different outcomes, yet most supplements are formulated as ‘one size fits all’.”

Vitamins contained in the matrix of the whole food are absorbed differently to the isolated nutrient.Credit: Getty Images

How safe is your stack?

If you were to eat a banana for breakfast, you’d be getting a dose of vitamin B6, vitamin C, and vitamin A within a tasty package of potassium, fibre, manganese, sugar, antioxidants and other phytonutrients.

“Nutrients in food don’t exist in a vacuum; they interact with each other and with the broader food matrix in complex ways that influences absorption, bioavailability, and effectiveness,” says Shine.

Why does this matter?

When we isolate those nutrients from whole foods and consume them in pill, powder or liquid form, we may be bypassing important regulatory mechanisms in the body.

“We don’t know what the long-term consequences of that are,” says Shine.

Loading

That’s before you consider how different forms of a vitamin or mineral behave in the body and may impact safety or bioavailability.

“Vitamins don’t just work in isolation, and we don’t yet fully grasp how high doses of isolated nutrients alter this delicate balance,” Crowe says.

It’s not just the potential effect of high doses.

“There’s also limited understanding of the cumulative effect of low-dose supplementation across multiple products,” says Shine.

Supplement stacking, where people take a combination of different supplements, vitamins and minerals to “optimise” health, fitness or beauty, has become more popular, but experts urge caution.

Individually, they might contain low doses, but together it may be a different story.

Shine explains: “The total daily dose can quickly exceed recommended levels, especially for fat-soluble vitamins and minerals with narrow safety margins.”

Kamal Patel reiterates that interactions between different supplements are “not well understood”.

“This wouldn’t be a big deal if side effects were all noticeable because in that case, you could stop taking a supplement if you noticed it was harming you,” he says.

“The problem is you can’t always know what’s going on in your body, and sometimes effects can be cumulative in nature.”

Pretty appealing, but what if you don’t have a deficiency?Credit: Getty Images

What happens if you don’t have a deficiency?

Even if we don’t have a diagnosed deficiency, there are various reasons people spend their money on vitamins and supplements.

Prevention, a sense of agency over our health, concerns about being at the “low-end” of healthy levels, the desire to “optimise” ourselves, and the alluring promises of products all contribute the appeal. I even have a smartly-branded jar of vitamins on my desk promising better energy levels and healthier hair and nail growth.

Who wouldn’t want that? And, what is the harm?

Beyond the potential for toxicity from taking too much, the long-term health consequences of taking vitamin supplements — especially in people with no deficiency — remain unclear, says Crowe.

“Many large randomised trials have found no benefit, and in some cases, harm, from long-term high-dose supplementation in an otherwise healthy group of people,” he says.

Along with fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) and some water-soluble vitamins, such as vitamin C and Niacin (B3), harms are also associated with excess calcium, folic acid and even turmeric supplementation.

Consider, for instance, curcumin which is the active compound in turmeric. It’s promoted for its anti-inflammatory properties as well as for supporting joint and bone health, and improving blood sugar control.

“But it can affect the body in several ways, including by interacting with liver enzymes and increasing bleeding risk,” explains Shine. “In Australia, at least 18 cases of liver injury have been reported, including one death.”

Loading

The authors of a 2024 analysis highlighted the need for long-term follow up of consumers of dietary supplements who are not deficient: “[They] may reveal adverse effects that can outweigh their potential benefits.”

Most of the available data comes from observational studies or short-term trials, which makes it difficult to draw strong conclusions about risk versus benefit over the lifespan, explains Shine.

Although taking a supplement gives the feeling of being proactive over our health, unless we have a deficiency, the answer does not lie in any pill or supplement stack, Crowe says.

“The foundations of a good diet, quality sleep and staying active will give you far more health benefits than a whole aisle of supplements could ever hope to deliver.”

Make the most of your health, relationships, fitness and nutrition with our Live Well newsletter. Get it in your inbox every Monday.

Most Viewed in Lifestyle

Loading