If you were in the market for niche curses, one of the more potent options, as The New York Times once joked, would be, “May you be profiled by Patrick Radden Keefe”.

Keefe has made a career of examining others with clinical clarity. He has carved out a space as one of America’s premier narrative non-fiction writers - sharp, precise, and surgical in his ability to reveal hidden truths. Over the past decade, his investigations have ranged from drug cartels and human trafficking to high art fraud.

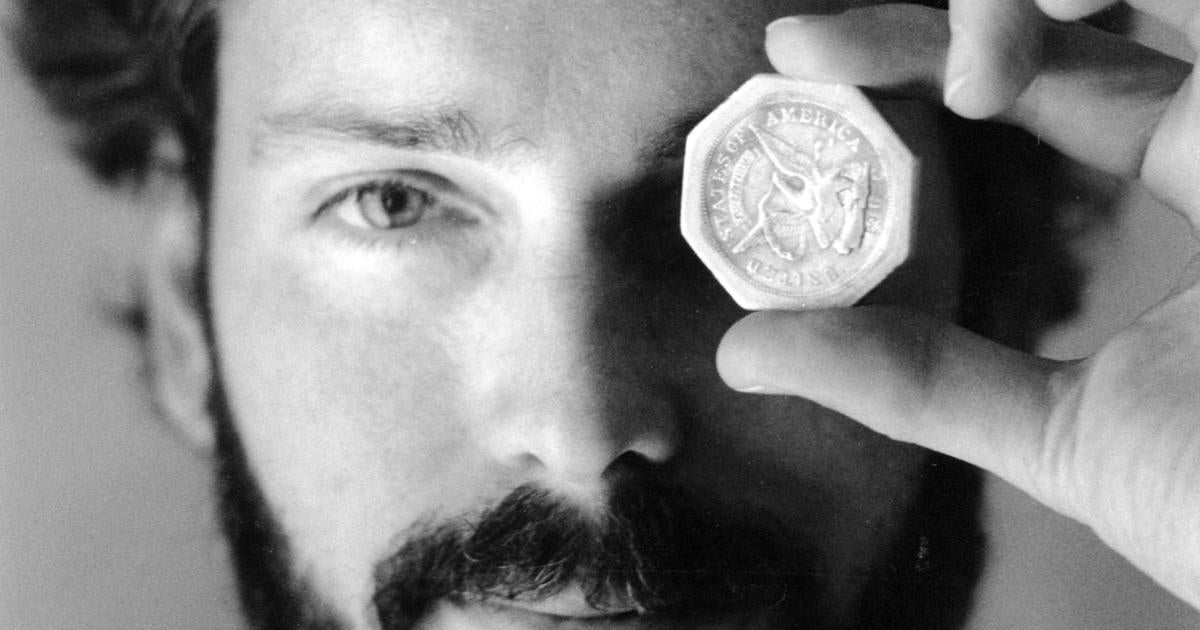

Patrick Radden Keefe has made a career of examining others with clinical clarity.Credit: Grainne Quinlan

Sitting across from him in a quietly buzzing Italian restaurant in Soho, I couldn’t help but think: thank God it’s me doing the interviewing. On the day we met he’d casually dropped he’d just come from meeting with a bereaved mother looking for the truth about her son’s death. He was coy about the topic matter, but I later discover it’s the subject of his much-anticipated new book, London Falling, to be released this April.

Keefe’s writing invites readers to wrestle with moral ambiguity, to view the world not in black and white, but in shades of grey. It was this obsession with detail and nuance that propelled Say Nothing – his deeply reported book on the Troubles in Northern Ireland – into one of the most talked-about releases of 2019.

Loading

Say Nothing doesn’t shy away from the complexities of the conflict, nor from the uncomfortable grey zones that make the decades-long sectarian struggle such a tragic and enduring subject. Centred around the mystery of Jean McConville, a mother of 10 who was kidnapped from her Belfast home in 1972, the book resonated deeply with readers and reignited debate in Ireland and abroad. Its success led to the recent screen adaptation – a nine-part Disney+ series that earned critical praise.

“It’s surreal seeing something you spent years buried in become this large-scale thing on screen,” Keefe says. “But the care they took with it - how seriously they treated the material – as genuinely moving.”

For him, it marked a shift to storytelling on a new stage, but one grounded in the same obsessive research and human focus that defines his work.

Keefe, who now lives in New York with his wife Justyna Gudzowska, a lawyer who specialises in international financial-crime policy, and their two sons, is also a man of dual identities. His mother, Melbourne-born academic Jennifer Radden, a professor of philosophy at University of Massachusetts, ensured his childhood in Boston was steeped in Australian stories and sensibilities.

“She used to read The Magic Pudding to us all the time,” he recalls. “It was the ultimate fantasy.” His American father’s cultural influence was more visible, but his mother made sure the family remained connected to her homeland – right down to securing Australian citizenship for her children.

“My mum wanted us to feel Australian,” he says. “Stories and imagination were a big part of that.”

To boost his credentials, he adds with a grin, his mother’s cousin is none other than David Parkin, the pioneering coach who led Hawthorn and Carlton to AFL/VFL premierships.

“We visited Melbourne a bit when I was a kid. I remember going to a game with my dad. I didn’t understand much of what was going on,” he says.

That sense of straddling cultures – of holding multiple narratives – may help explain Keefe’s knack for inhabiting the murky middle of moral dilemmas. His quiet persistence, shaped early on, shows in everything he writes: long form essays for The New Yorker, award-winning books, and genre-bending podcasts.

Empire of Pain, his 2021 Baillie Gifford winning exposé of the Sackler dynasty behind Purdue Pharma and the opioid epidemic, is unflinching.

Lola Petticrew as Dolours Price in the television adaptation of Say Nothing.

“There’s no ambiguity there,” he says. “You know who the bad guys are.” But with Say Nothing, clarity proves elusive. “You’ve got hardliners on both sides calling it propaganda - IRA, British. That’s where I want to be. In the middle. If both extremes are angry, you’re probably doing your job.”

Keefe’s stories are always driven by people - especially those on the margins. “I never wanted to just write about a subject,” he says. “I want intriguing people, moral tension, ambiguity. A yarn. You should think you know where the story’s going, and then – bam – it turns.”

He describes his reporting process like a magician walking through a trick: pulling threads, hiding reveals until just the right moment. “It’s like taking apart a watch. I used to read New Yorker articles and count how many people were quoted, how often. I’d study them like puzzles.”

Loading

His 2020 podcast Wind of Change, which investigates the rumour that the CIA secretly wrote the Scorpions’ Cold War-era power ballad, reflects that same fascination with narrative subversion. “I love stories like that, where the listener has to follow along, not knowing where it will lead,” he says.

These days, those bylines he once analysed are now his peers. But getting into journalism wasn’t a straight shot, there were plenty of knock-backs along the way.

“It’s not an apprenticeship model,” he says. “You can’t just show up and rise through the ranks. You’re on your own.”

London Falling is Keefe’s fifth book (six, if you count Chatter, “which I’d rather you didn’t”). It builds on his 2024 New Yorker article into the last months of the life of London teenager Zac Brettler, who fell to his death from a luxury apartment overlooking the Thames in 2019. The tragedy prompted his parents to uncover the disturbing truth that he had been living a double life as the fictional son of a Russian oligarch.

Such if Keefe’s gripping story telling ability he even, improbably, once fielded a request from El Chapo’s people asking if he’d ghostwrite the former Mexican drug lord’s memoir.

“My four-year-old once accidentally FaceTimed a cartel contact,” he laughs. “They just stared at each other. My son holding the phone, the guy staring back - neither of them had any idea what to do.”

Danger has hovered at the edges of his work. “I’ve had to leave a few situations quickly,” he says. “But I’m American. I can get on a plane. The journalists who live there, who can’t leave - that’s real risk.”

Still, the emotional toll is real.

“You put so much into a story. You want it to be definitive,” Keefe says.

Loading

“But then life goes on. These people, they keep living. There’s always more. You can’t just report on something, you have to live with it. You have to let it change you.”

His patience and obsession aren’t just professional tools - they’re a kind of philosophy.

Keefe talks a bit more about the culture of journalism - the turf wars, the ego, the scarcity mindset that leads reporters to guard their stories like dragons hoarding gold. “I hate that,” he says. “I don’t think truth has to come out under my byline. It just needs to come out.”

Would he write an Australian story one day?

“I would really love to,” he says. “I just need to find the right one.”

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.

Most Viewed in Culture

Loading