The Reserve Bank has always denied that its manipulation of short-term interest rates to slow or hasten the growth in demand for goods and services plays any part in worsening the cost of home ownership. But I doubt this.

The biggest and most pressing economic problem Australia faces is nothing new: the ever-worsening ability to afford to own the home you live in. Young people feel this acutely, and it seems to be the single biggest factor causing their growing disillusionment with the deal they’re getting and the democracy that produces an economy run like ours.

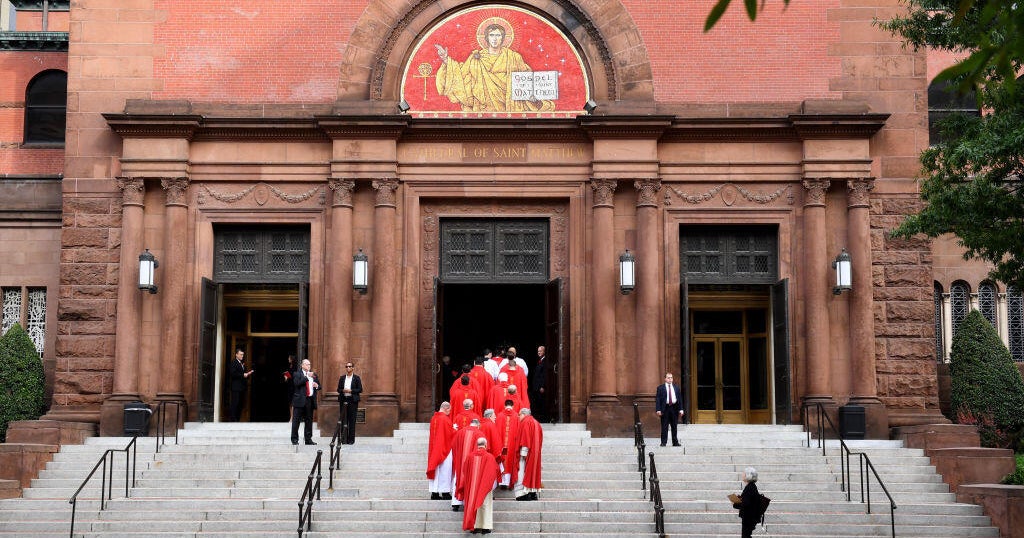

The RBA, led by governor Michele Bullock, has long denied that interest rate changes have an impact on property prices.Credit: Marija Ercegovac

In response, there’s a growing view among economists that, however many parts of the economy need reforming, the first thing we should fix is home ownership. Once most Zoomers are confident that they’ll be able to own their home the way their parents and grandparents do, they’ll feel a lot less alienated.

One thing we’ve learnt is that home unaffordability is the product of many factors: not just negative gearing artificially inflating demand; the home-building industry’s inefficiency reducing its output; nor zoning regulations used to stop newcomers living in the most accessible parts of the city, but all of them – and probably more.

So whether the activities of the Reserve Bank – our heavy reliance on fiddling with interest rates to manage the macroeconomy – are also contributing to the excessive rise in house prices is overdue for examination.

The Reserve’s denial that its ups and downs in interest rates have any lasting effect on house prices is based on the plausible claim that it’s ups and downs cancel each other out, leaving the average level of short-term rates little changed.

We’d be better off ditching monetary policy completely as an instrument for managing the macroeconomy.

But it’s also based on a simplistic, mechanistic view of how markets work, with demand and supply responding to changed prices in a quite linear fashion. That is, it takes no account of the way people’s actions can be influenced by their expectations about how prices will move in the future.

The thing about the Reserve’s manipulation of interest rates is that it’s relatively predictable. What starts going down will keep going down, and what starts going up keep going up. We’re seeing the effects of such expectations at work right now.

In the less than eight months since the Reserve began it latest easing cycle on February 19, average house prices have jumped 5 per cent. Why? FOMO – fear of missing out. We’ve all been trained to know that, as soon as the Reserve starts cutting rates – and thus making it easier to afford a huge loan – many people will start buying places.

Loading

When they do, house prices will start rising. In which case, I’d better buy my place ASAP. And when many other people do the same, demand exceeds supply and prices rise – thus making the expectation self-fulfilling.

Now, if expectations were perfectly symmetrical, this wouldn’t matter. It would be offset when the Reserve made the initial rate rise of a tightening cycle. Demand for homes would suddenly drop because more rises were expected, thus pushing house prices down.

What’s more likely, however, is that house prices are “sticky downwards”. If so, “monetary policy” – the manipulation of interest rates – has a ratchet effect, pushing house prices up but not down. If so, that’s a serious unintended consequence of using interest rates to manage demand.

And I’m indebted to my former understudy, Gareth Hutchens, for noticing some remarks by Stephen Grenville, a former deputy governor of the Reserve, acknowledging another respect in which monetary policy leads to higher house prices. (By the way, please don’t look for Hutchens’ Sunday economics column on the ABC site. You might decide he’s smarter than his former master.)

Grenville said the Reserve had yet to resolve a problem with its use of interest rates to influence increases in the prices of goods and services: this also affects the prices of assets, including property.

The inflation-targeting framework encourages policymakers to keep cutting rates as the inflation rate keeps falling – even if it falls below the target range, as it did for more than a year before the arrival of COVID.

Grenville said an ever-lower interest rate does very little to increase growth in real gross domestic product, but it has a big effect on asset prices such as houses and shares (which are often bought with borrowed money).

He said people need to realise that monetary policy has its limits, and if we keep cutting rates below a certain point it can cause economic problems, especially with property prices.

Oh, dear. What can we do? Well, one simple response would be to abandon the convention that almost all the work in the short-term management of aggregate demand must be left to monetary policy. That is, more of the load should be carried by “fiscal policy” aka the budget.

But the episode we’re just leaving – where we laboured painfully for about three years using monetary policy to end the inflation surge caused by COVID and the response to it – has convinced me we’d be better off ditching monetary policy completely as an instrument for managing the macroeconomy and shift to one with fewer unintended consequences and adverse side effects.

We have at our fingertips a much fairer and more efficient instrument to restrain or encourage demand as required.Credit: Dominic Lorrimer

Partly because the interest businesses pay is tax deductable, the effect of higher interest rates is concentrated on the one-third of households with mortgages. They get really squeezed, whereas people who own their homes outright, and even renters, are let off lightly.

This is obviously hugely unfair on home-buyers. We should be using an instrument that spreads the squeeze to a much higher proportion of households. But monetary policy’s narrow application makes it inefficient as well as unfair. Because so few people are directly affected, it takes much longer to work.

And the joke is that, unlike all the other rich economies, and as first suggested by Hutchens, we have at our fingertips a much fairer and more efficient instrument to restrain or encourage demand as required: a temporary increase or reduction in the 12 per cent compulsory superannuation contribution rate.

The Business Briefing newsletter delivers major stories, exclusive coverage and expert opinion. Sign up to get it every weekday morning.

Most Viewed in Business

Loading