Opinion

December 9, 2025 — 5.30am

December 9, 2025 — 5.30am

Sometimes, the best thing to do in a cricket match is nothing. Often, it is the only thing to do. All sports have their tactical lulls, but cricket’s last for hours.

At any given moment, most of the people in the game, on the field and off, are not doing what they were picked to do. Most of the time, batters aren’t batting, bowlers aren’t bowling, but everyone at some point is fielding, which is mostly doing nothing. The game runs on latent energy. What a team has up its sleeve at any time can be as important as the hand it is playing.

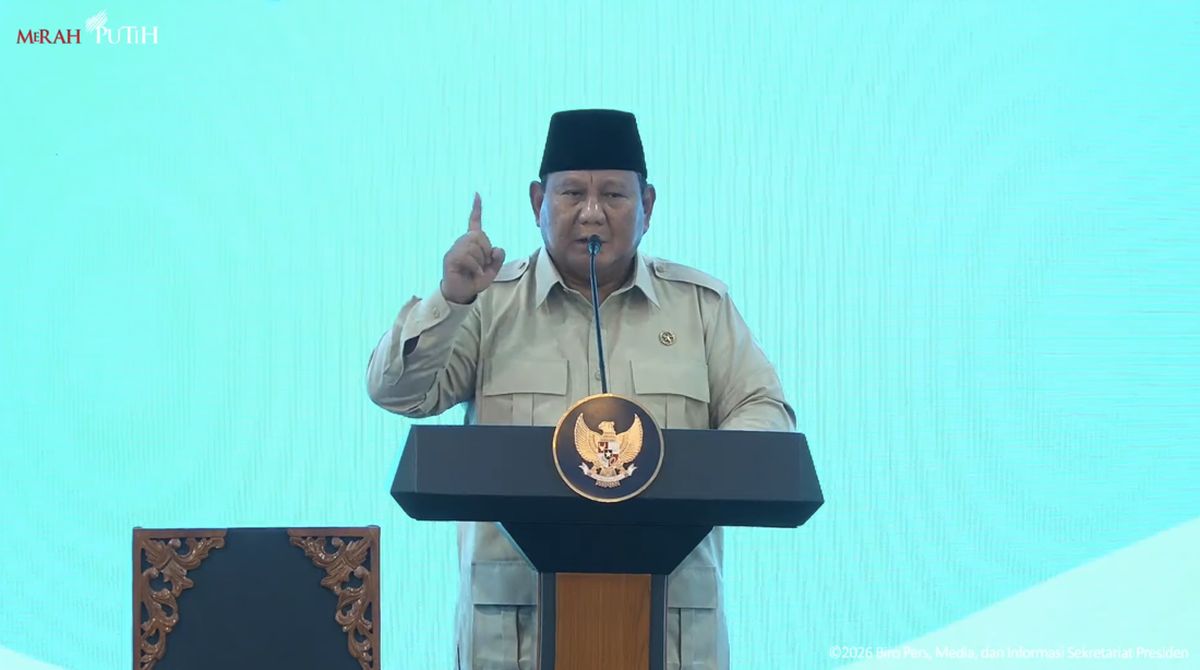

Scott Boland and Mitchell Starc’s slavish devotion to the cause proved the perfect foil for Bazball.Credit: Getty Images

Bazball sits uncomfortably in this paradigm; it implies a need for constant, frenetic, stampeding action. Bazball abhors a dot ball like nature abhors a vacuum. The Brisbane Test again was driven by Bazball dynamics; even Australia were swept up, belting along at five an over for most of their first innings until it developed a speed wobble that threatened to derail it.

What happened next was the fulcrum of this match, and it was little to nothing. This was the work of tailend batters Mitch Starc, Scott Boland, Michael Neser and Brendan Doggett. It was industrious nothing, applied nothing, dedicated nothing, slaving over nothing, but nothing just the same. For the balance of the innings, the run rate was not much more than 2½ an over. The important thing was that it was over after over.

It wasn’t really nothing, of course. Block, leave, cover up, stall, but with a counter jab every now and then so that they were not seen as sitting ducks; these are the passive-aggressive measures by which Australia’s tailenders smoked England out of the game. Long ago, after a false start in Test cricket, Steve Waugh came to the conclusion that a stout defensive shot to keep out a good ball was sometimes just as demoralising to a bowler as a boundary from a bad ball, and so was reborn one of the great Australian Test careers.

In these times, Steve Smith has elevated the leave to a sally in its own right, a thrusting, sabre-rattling non-play. Marnus Labuschagne mimicked him and so the leave became an Australian cricket artefact. We saw nothing so macho from Starc, Boland et al., of course, but their intransigence at the crease slowly worked on England like body punches until they were melting against the ropes in the Brisbane swelter. Later, as bowlers, they got to deliver the knockout blows.

That’s not to say that all Test cricket must be played as a study in inertia. Fifty years ago, it was, and it was so dull that the game nearly died of its own boredom. The pace changed long ago, long before Bazball. The West Indies patented calypso cricket, and Mark Waugh is the first man I saw play both a deliberate upper cut and a reverse sweep in Test cricket.

White-ball cricket revolutionised the game. Bazball is a natural further evolution. It’s a great idea; it’s the application in which England is too often injudicious. One of the game’s eternal verities is that batsmen can’t win a Test match in half an hour, but they can lose one in that time. Exhibit A: the first Test. Exhibit B: the second Test.

In Test cricket, you have to know when to go and when to do nothing, or not much. In England’s first innings, it wasn’t that Joe Root did nothing, but that he did nothing silly, nothing reckless, and so played one of the best of his many hundreds.

Jofra Archer: tough day at the office.Credit: Getty Images

The less-is-more principle could be seen at work on another plane. What’s best, to bowl at 135km/h and take six wickets, a la Michael Neser, or 150km/h and take one, as per Jofra Archer? Asking for some auld friends. Archer, a made-to-order Bazballer, huffs and puffs, but he is yet to dismiss Smith in Test cricket.

Bazball or no Bazball, two other old truisms still apply. Catches still win matches. And a batsman-wicketkeeper will work, but a good wicketkeeper-batsman is a rare and precious player. Alex Carey’s craft in this match was nothing short of astounding.

Loading

At length, England grasped the need do nothing. It was the only ploy they had left. Ben Stokes we already knew had more gears to his batting game than any player alive, and for as long as he was in, there was a frisson around every live screen in the country.

Like the Australian tail, his was a subtle sort of nothing, punctuated at long intervals by a retort to remind everyone of what he still could do. His 50 was his second slowest in Tests, behind only Headingley 2019, ominously. But it looked like the foundation of 150. England, however, had left it far too late to do what the match required of them for a while earlier in the match: strategic, classical, Test-quality nothing.

News, results and expert analysis from the weekend of sport sent every Monday. Sign up for our Sport newsletter.

Most Viewed in Sport

Loading