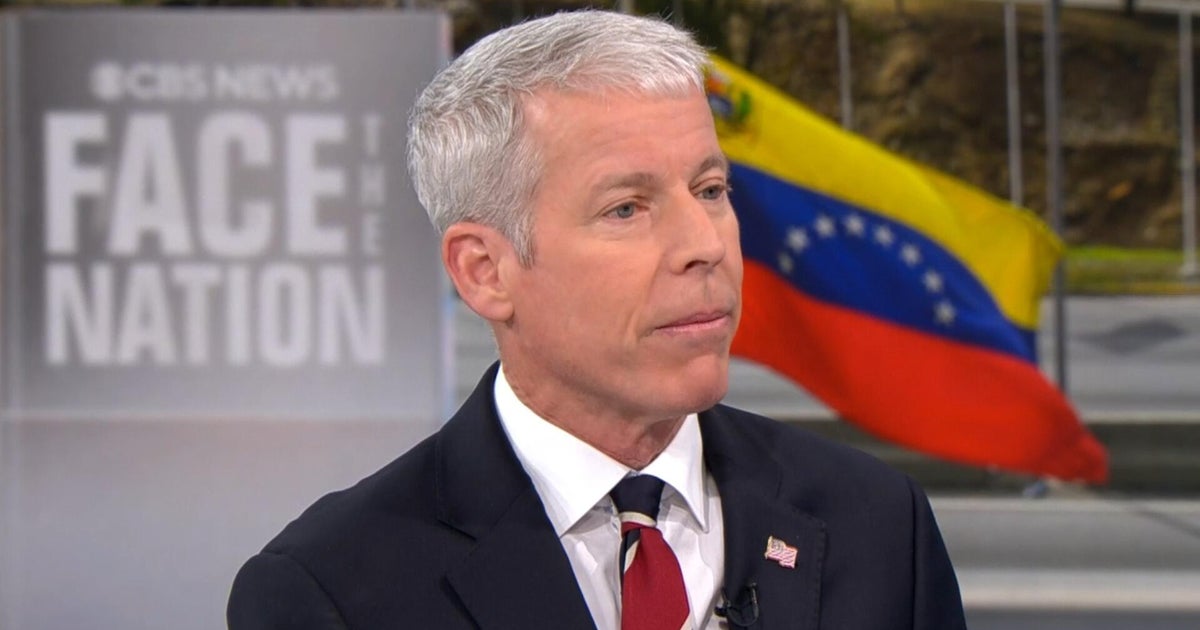

There are more than 1000 electronic music instruments in the MESS collection, many of them priceless, but none is quite the match for the roll of paper Robin Fox, co-founder with Byron Scullin of this “living museum”, is holding.

“This is the actual piece of punch-card tape that produced the first ever computer music,” he says excitedly. “Not in Australia – in the world. This is like the Holy Grail.”

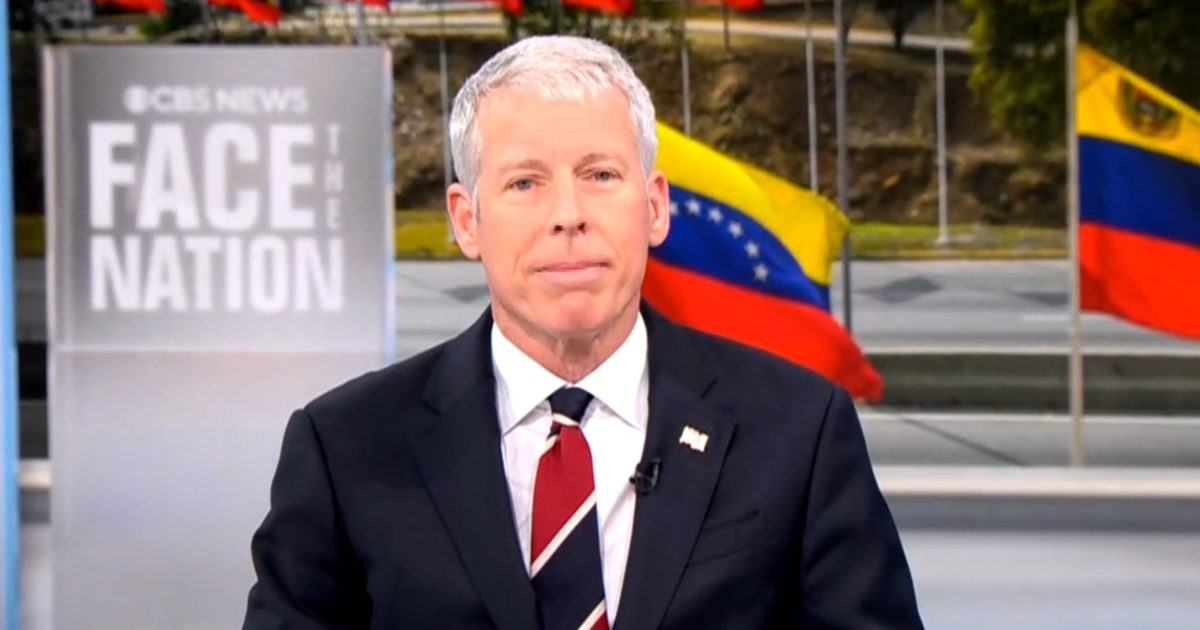

Robin Fox, co-founder of MESS, with a 1979 Fairlight CMI.Credit: Simon Schluter

The tune was The Colonel Bogey March (think “Hitler has only got one ball” and you’ve got it), and it was rendered in electronic form by CSIRAC, Australia’s first computer (the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Automatic Computer), in 1951.

There’s no known audio recording, but that strip of paper tape – which has taken a colleague a good 10 minutes to locate today – is the next best thing. Arguably, even better.

Which prompts the question: why the hell are you holding it in your bare hands?

“We call ourselves a living museum, but the living part is more important than the museum part,” Fox says. “There’s an orthodoxy in the conservation of things that you don’t use them, you don’t touch them, you white-glove them, and you barely even look at them. And the tragedy for me in terms of musical instruments is that you never hear them again. But these things are musical instruments, and they need to be played.”

At MESS – or the Melbourne Electronic Sound Studio, to give it its full name – people are encouraged to touch the displays. To play with them. To make sounds and record them to their laptops, to take them away and maybe even turn them into hit songs.

A theremin from the 1930s. You play it by moving soundwaves with your hands.Credit: Simon Schluter

“I call it preservation through use,” says Fox, adding that some people refer to the collection as a gym for synths. “Electronic musical instruments need to be switched on regularly. They need to be played regularly. Capacitors dry out, so they just won’t work any more, or they catch fire when you turn them on. It’s about the components needing warmth going through them.”

MESS began a decade ago when Fox laid out a pitch to Wally De Backer, better known as Gotye, for a permanent public collection. “He loved the idea,” says Fox. “Wally had always been really interested in the more esoteric side of electronic music history.”

With the royalties from his 2011 global hit Somebody That I Used to Know, De Backer had started buying rare pieces, including a theremin from the 1930s and a Hammond Novachord – released in 1939, it was the first commercially available synthesiser – both of which are now in the MESS archive. And available to be played.

The punch card paper roll that was used to produce the first music ever played by a computer, in Melbourne in 1951.Credit: Simon Schluter

MESS opened in 2016, but it was the very definition of underground, housed in the basement of the Meat Market in North Melbourne, in a long bluestone room once used for ice storage (so cool).

On Friday, it opens the doors to the public for the first time in its new home at Federation Square, opposite NGV Australia.

“We’re going basically from zero to hundreds of thousands in terms of foot traffic a year,” says Fox. “I don’t know what that will mean. This is still a grand experiment, as far as I’m concerned.”

Loading

Well, that’s fitting. After all, experimentation is what this collection is all about.

One of the most exciting pieces on display is a Fairlight CMI, developed in Sydney by Kim Ryrie and Peter Vogel (off the back of an earlier synth called the QASAR, built in Canberra by Tony Furse).

Released in 1979, it’s a beast of a thing, with a green-screen monitor, a keyboard, a disk drive into which eight-inch floppies containing sampled sounds could be loaded, a microphone for recording those sounds, and a magnetic pen that could be used to manipulate soundwaves on the screen.

It was unwieldy, and expensive – “it was the price of an apartment”, Fox says – but for the likes of Peter Gabriel and Kate Bush it was a must-have. And that bass drum sound in John Farnham’s You’re the Voice? Fox says it is “the sound of a slamming car door in a Bulleen driveway” – recorded and played as a sample through the Fairlight.

Whether the instruments are turned on or not, one thing this collection says loud and clear is that Australia has been much more than an (eight-)bit player in the evolution of this branch of music making.

“We’re all obsessed with how many gold medals we can win at the Olympics,” says Fox. “But we are punching well above our weight in terms of the impact we’ve had on electronic music globally.”

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in Culture

Loading