It is an extraordinarily bitter feud. A public brawl between the state’s top prosecutor and a NSW District Court judge has spawned a police investigation, two parliamentary inquiries and a court fight.

In isolation, it would appear to be a dispute between two senior legal figures in Sydney: Judge Penelope Wass, who was appointed to the District Court bench almost a decade ago, and Director of Public Prosecutions Sally Dowling, SC, who is less than halfway through her 10-year term.

But it is just one front in a war that has been raging for well over a year between the NSW Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions and a group of District Court judges over sexual assault trials. It raises serious questions about the consequences for criminal matters before the court.

December marked the latest outbreak of hostilities. Wass lobbed an explosive 68-page submission about Dowling and her office at a NSW upper house inquiry in November, and it was published on the parliamentary website with no fanfare late on December 4. It was front page news in The Australian the next day.

‘Deliberate and targeted’

In her submission, Wass accused the ODPP of giving information to Sydney radio station 2GB in October 2024 about proceedings involving an Indigenous youth to “embarrass and defame” her.

She alleged that “it forms part of a deliberate strategy by some of those within the ODPP, including Ms Dowling” to attack her personally or to influence her judicial conduct, or both.

Wass said the committee might consider referring senior ODPP officers to the governor “for removal from office”.

The judge had invited the Indigenous teen to perform what she called a Welcome to Country before he was sentenced for serious crimes. He delivered a short acknowledgement of “the traditional owners and custodians of this land” via video link.

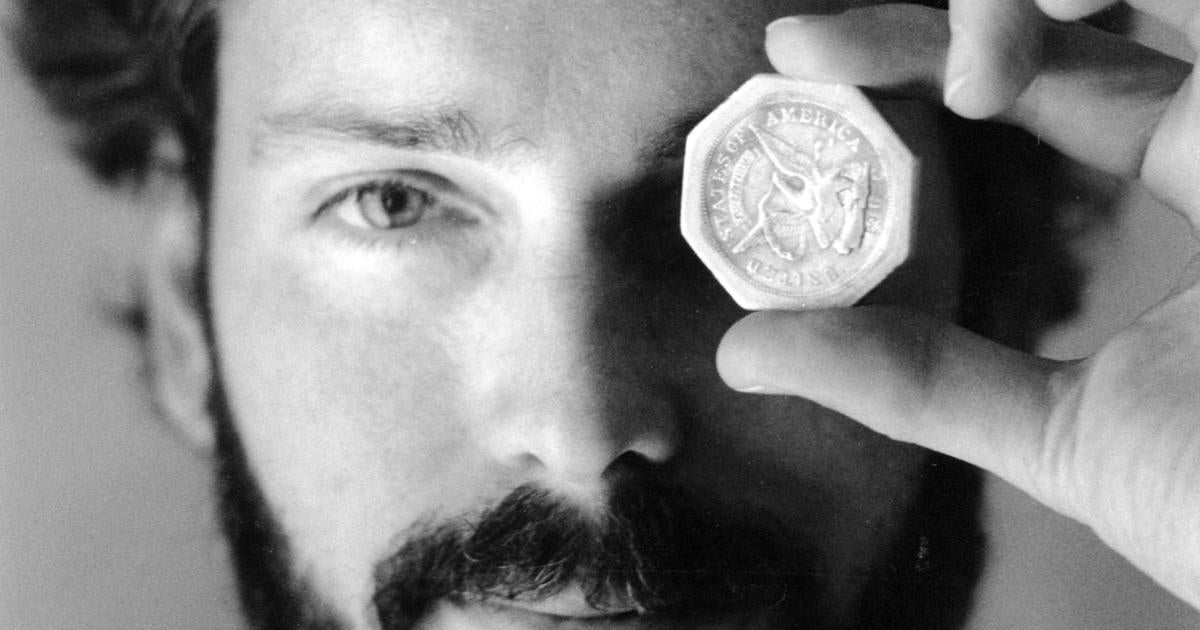

Ben Fordham, host of 2GB’s morning program, described the “welcome” on air on October 25, 2024, as a “local scandal”. The youth had committed an aggravated break and enter involving the sexual touching of an elderly woman.

Ben Fordham described the “welcome” as a “local scandal”.Credit: Nine

Wass extended an invitation for the teen to conduct further “welcomes” in court in the future, but she said this was conditional on him not reoffending.

He had already served a significant period in custody and was released immediately on parole.

The offender had received the maximum sentence available, Wass said in her statement. The judge said she had “received derogatory public statements and threats from consumers of the 2GB story almost immediately after it was aired”.

“No one from within the ODPP expressed any concern to me [during the sentencing] ... Instead, the ODPP moved to disclose information to 2GB and a ‘trial by media’ ensued,” Wass said.

She said she made the invitation to engender an “increased sense of identity and self-esteem” in the youth, with a view to his rehabilitation.

The solicitor who acted for the Indigenous teen told the inquiry he supported the judge inviting him to perform the “welcome” or acknowledgement.

ODPP ‘gave the story’ to 2GB

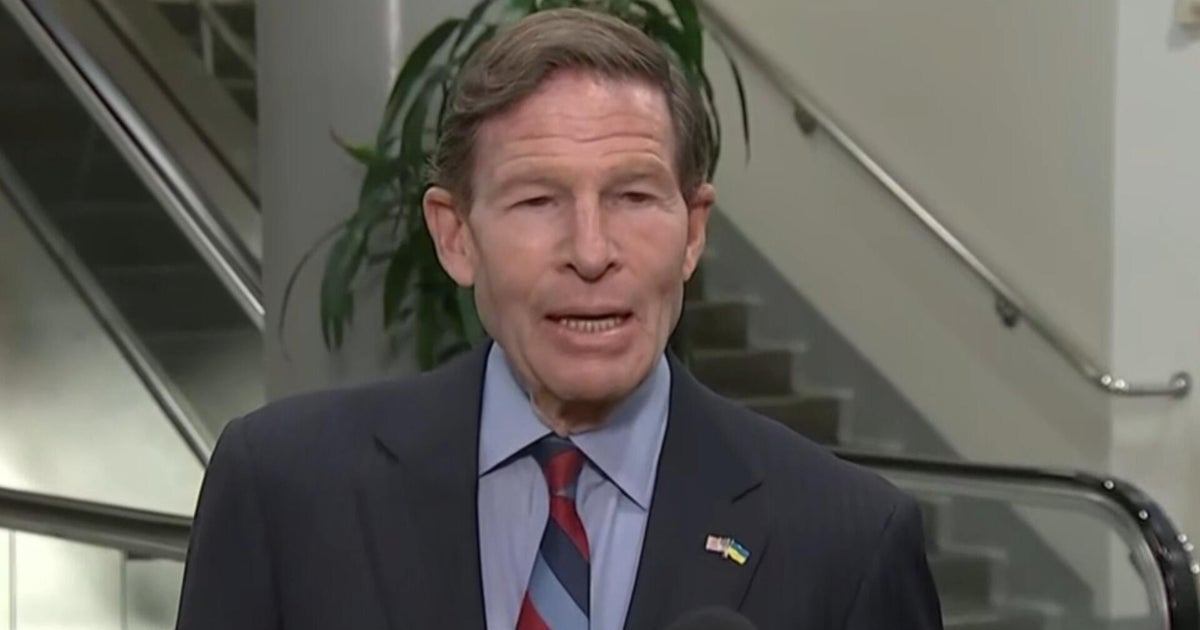

Dowling gave evidence before the inquiry on December 5. She accused the upper house committee of a “disgraceful” denial of procedural fairness in publishing Wass’ submission late on December 4 without giving her a copy. She had believed the inquiry had a wholly different focus.

The top prosecutor admitted during her evidence that her office effectively “gave the story” about Wass to 2GB, but she said she had not become aware of this until about “two days ago”.

“At no time did I direct or ask for the [ODPP] media manager to provide the story to 2GB,” she said.

Dowling’s evidence prompted the inquiry to call ODPP media manager Sally Killoran to appear. Killoran revealed that Dowling was at a meeting with her and an external media consultant the day before the 2GB broadcast.

There are legitimate questions about why Dowling’s office gave a story about a sitting judge to a news outlet, at a time when Dowling and Wass were already locked in a bitter dispute. But just why it attracted the attention and resources of a parliamentary inquiry with a seemingly unrelated remit is unclear.

Sally Dowling gave evidence to the NSW Parliament.

In a statement to the inquiry on December 17, the ODPP said it was “difficult to avoid the inference that the committee intended to ambush [Dowling] … with the judge’s submission”.

Dowling suggested during her evidence that the upper house committee was conducting a “de facto” inquiry into the ODPP “under the guise” of an inquiry into NSW law.

An unusual inquiry

The inquiry has some unusual features. Ostensibly, it was set up to examine the adequacy of statutory protections to prevent the identities of children in criminal proceedings being published. It was self-referred by the upper house justice and communities committee in October, a year after the 2GB broadcast.

The Dowling-Wass saga was described during hearings as a “case study”. It appears to be the only case study explored in detail, and it has been vigorously pursued.

The inquiry is due to report on February 20, leaving little time to canvass broader issues.

Under NSW’s Children (Criminal Proceedings) Act, there are broad prohibitions on publishing or broadcasting information to the public identifying a child involved in criminal proceedings. Criminal sanctions apply.

Penelope Wass cited MP Alister Henskens in a statement to police.Credit: Rhett Wyman

Wass said in her submission that she contacted the head of the NSW Police cybercrime squad after the 2GB broadcast because she was concerned this prohibition may have been breached.

The judge in a statement to police said NSW Liberal MP Alister Henskens, the shadow attorney-general, had told her that someone within 2GB provided him with a screenshot of information about the Indigenous youth’s case before he was invited to discuss it on air.

Henskens told her that the document “included an icon with an OPP identifier on it”, Wass said in her police statement.

Killoran subsequently told the inquiry that she gave a screenshot to 2GB of an internal ODPP database showing details of the case, including the youth’s name, to help it “confirm the story”.

However, 2GB did not publish or broadcast his name to the public. Dowling told the inquiry that “provision of that screenshot did not involve any offence”, but she was not aware at the time that Killoran had sent it and she had not authorised its disclosure.

Loading

Killoran had started in the role in late July 2024 and is not legally trained. She told the inquiry she made a mistake in releasing the screenshot because she had since learnt the contents of the database were for the eyes of ODPP staff only. She was issued a formal caution and counselled after an internal investigation.

“On 21 March 2025, NSW Police advised the ODPP that they had concluded their investigation. Police took no further action reflecting, as I said, that no offence had been committed,” Dowling said in her evidence.

Wass in her submission said that “on the scant information currently known, the ODPP is correct to contend that no breach of that provision has occurred”.

However, she said the outcome of the police and internal ODPP processes “demonstrates that existing sanctions are ... unlikely to provide either meaningful accountability or general deterrence for breaches of children’s identity protections”.

The ODPP in its statement to the inquiry said it would be a “misuse of the parliament’s powers and privileges” for the inquiry to be “misdirected from its terms of reference because the judge is dissatisfied with the outcomes of the proper processes that have taken place to date”.

The meeting with Dowling

At the time of the 2GB story, a string of stories had been published in The Australian about court decisions blasting Dowling’s office.

District Court judges, including Wass, had taken aim at the ODPP in judgments over its handling of sexual assault prosecutions and suggested it was running unmeritorious cases.

The criticisms were unusually strident, and two judges – Robert Newlinds and Peter Whitford – met with disapproval from the Judicial Commission after Dowling lodged complaints against them over their remarks. The two decisions are no longer accessible online.

The judicial watchdog said both judges had denied Dowling’s office procedural fairness in making the criticisms without inviting a response, and it said Whitford deliberately used his judgment as a “tool” for public criticism of the ODPP.

District Court Chief Judge Sarah Huggett.Credit: Dan Himbrechts

Although Dowling did not make a complaint to the commission about Wass, the pair have made complaints about each other in different forums. Dowling complained in May 2024 to the District Court Chief Judge about Wass’ directions to witnesses in three sexual assault cases, and Wass complained about that move to the Bar Association. The association said it could not investigate.

By mid-2024, the pair’s working relationship had soured considerably.

The Australian has been a constant in reporting on the fray, which has also raised the ire of Dowling.

The parliamentary inquiry has exposed the inner workings of the ODPP around this turbulent time. The office engaged the services of an external media consultant in April 2024.

Dowling in a supplementary statement to the inquiry on December 16, after Killoran gave evidence, said she was present at a meeting on October 24, 2024, with Killoran, a principal legal adviser from her office, and a consultant from strategic communications advisory firm GRACosway.

This was the day before the 2GB broadcast.

“During the meeting there was general discussion about various topics, including Judge Wass’ invitation to the young person to give the ‘Welcome to Country’,” Dowling said. “It was discussed that this was a newsworthy story.”

She said Killoran had “asked something along the lines of what would happen if the media had the story” but she did not understand this to mean Killoran was proposing to raise the story with any journalist. Dowling said she “inferred that the media already had the story”, and she did not give “any substantive response”.

Killoran gave evidence that she “raised the topic of whether I could proactively pitch the story to the media” and suggested News Corp’s The Daily Telegraph.

“The external media consultant suggested that 2GB would probably be more interested. No one objected to this suggestion and, therefore, at the time, I believed I had approval to pitch the story,” Killoran said.

The inquiry may call Dowling to give further evidence in February about this meeting. However, a NSW Court of Appeal ruling in December made clear that inquiries’ existing powers to compel witnesses to appear are constitutionally invalid.

Feud continues

This is far from the end of the toxic fight. The Court of Appeal heard on December 18 that four criminal matters involving Wass had been “paused” because the ODPP wants her to recuse herself on the grounds of apprehended bias. This is not an allegation of actual bias, but of the appearance of it.

Loading

This has triggered a Court of Appeal case about whether it would be a breach of parliamentary privilege for Dowling’s office to rely on Wass’ submission as the basis for its recusal applications. A hearing has been set for February.

Upper house inquiry chair Robert Borsak, of the the Shooters, Fishers and Farmers Party, said in a letter to the NSW upper house president that the committee was concerned the recusal applications “may be an attempt to intimidate an inquiry witness”, namely Wass.

On that basis, Dowling is now facing a separate inquiry by the parliament’s privileges committee about whether the applications would amount to a contempt of parliament. While this is not a criminal offence, a contempt finding would be another blow to the ODPP.

There appears to be no end to the controversy, and its consequences have now spilled into the courtroom.

2GB is owned by Nine, the publisher of this masthead.

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.