Nathan, fellow barrister Richard McGarvie (later governor of Victoria), John Cain (later premier) and John Button (later a legendary senator) formed a group known as the Participants that cleaned out communist influence in the Victorian ALP branch.

Decades earlier in NSW, solicitor and Labor member Jim McClelland launched an industrial case against a union strongman designed to break the communist influence in heavyweight unions. He briefed the little-known barrister John Kerr for the court battle.

McClelland and Kerr were both working-class kids with brilliant minds who flirted with Marxism and became great mates, which caused Jim to reflect at the time of Kerr’s death: “I was never a good judge of character.”

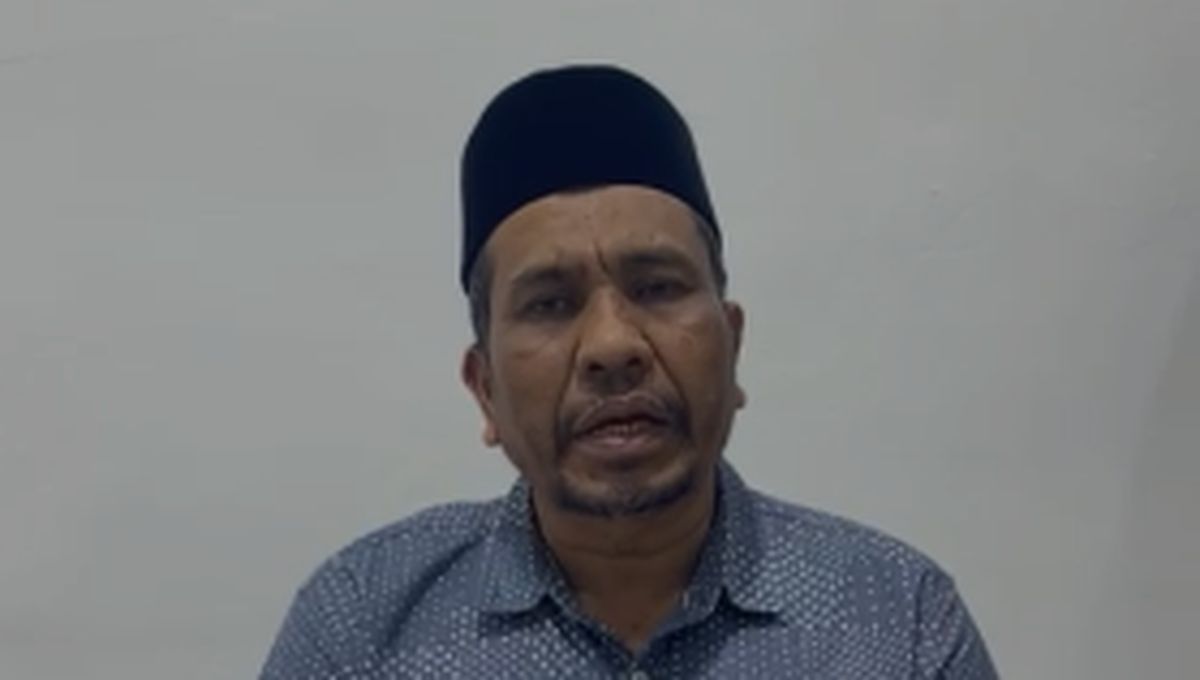

Labor senator Jim McClelland addresses a rally in October 1975.Credit: Fairfax Media

McClelland, known as Diamond Jim, was a federal senator from 1971 until 1978. Whitlam, believing Kerr (who had considered standing for election as a Labor candidate) was one of them in 1974 appointed him governor-general.

Nathan recalls: “Inflation was out of control (in 1974 it was nearly 16 per cent) and it was destroying the savings of the middle class. In one of Gough’s rare rational economic thoughts, he decided to put someone competent into a position to try and rein it in, and he decided to give the Diamond a run.”

McClelland was appointed minister for manufacturing industry and minister for labour and immigration. His brief was to rein in runaway wages and try to control crippling inflation.

Barrister Nathan had appeared as McGarvie’s junior at an Arbitration Commission hearing, arguing successfully against a massive wage claim by saying it would turbocharge the inflation cycle.

“Inflation was wiping out the country,” Nathan recalls.

Nathan’s work in the court and his ALP background impressed McClelland, who offered him a job as cabinet adviser, which meant he had to give up his position at the Bar.

Whitlam’s government, re-elected in 1974, had a majority in the House of Representatives but not the Senate. As it lurched from scandal to scandal in October 1975, Liberal Party leader Malcolm Fraser used his Senate majority to block supply bills used to fund government.

He said he would immediately pass the bills if Whitlam called an election, which he refused.

Kerr, quite properly, was updated by both Whitlam and Fraser. But quite improperly took secret guidance from his friend and High Court judge Sir Anthony Mason.

Governor-general designate John Kerr and prime minister Gough Whitlam were probably not discussing the meaning of reserve powers at this meeting in 1974.Credit: Fairfax Media

Those conversations showed that within days of supply being blocked, Kerr was considering sacking Whitlam long before he finally acted.

According to Nathan, the governor-general then began a plot of disinformation.

Far from being a child of the left, Nathan says Kerr was desperate to be accepted by the establishment and old-school conservatives.

“Kerr turned out to be a plant from the right,” he says. “He was all things to all people all the time. He was the ballet dancer who paraded around in the tightest of tights. He was a frightful person.”

About a week before the Dismissal, Nathan was in his boss’s Canberra office when the minister’s private phone line rang. “He had two government lines that went through his office switchboard and a private, direct line for family and his closest friends.”

The call was from Kerr. “How he had the number I have no idea – perhaps the Diamond gave it to him, I don’t know,” says Nathan.

“I could only hear part of the conversation, and it was all jolly, jolly hockey sticks. It was a private call, and so I left the office. The Diamond came out and said, ‘It’s going to be all right, he’s with us.’

“The enormous impropriety of the governor-general contacting a minister directly is obvious. It doesn’t matter if they were friends, it was grossly improper. He was the Queen’s representative and should only deal directly with the prime minister.

“I have no doubt Kerr was using his friendship with the Diamond to attempt to deceive the government. He expected the message to go to Whitlam.”

‘I have no doubt Kerr was using his friendship with the Diamond [Jim McLelland] to attempt to deceive the government.’

Former Supreme Court judge Howard NathanThe Kerr-McClelland phone call and Nathan’s subsequent private conversations with the senator has left him convinced it was a set-up. If Whitlam believed Kerr was about to turn on him, the prime minister would have got in first, asking the Queen to remove the governor-general from his post. The assurance to Kerr’s friend McClelland was designed to assure Whitlam there would be no Pearl Harbour.

But Kerr was mistaken. By this time, the government was dysfunctional and Whitlam was only listening to a handful of his closest advisers.

Nathan says: “Only God spoke to Gough, and even she was a little frightened.”

Top hat on a top rat. Kerr with Fraser (left) and Whitlam.Credit: Four Corners

So why did he want to assure Whitlam he was onside? He was receiving secret advice from High Court judge (and close friend) Mason on the legality of removing Whitlam’s elected government and installing Liberal leader Fraser as prime minister.

When the supply crisis began, Kerr immediately and informally asked Mason if the governor-general had the power to sack Whitlam and appoint Fraser if the latter agreed to immediately call a general election.

Mason said he had the constitutional power. Years later he explained his role. “I said that, in my view, the incumbent prime minister should, as a matter of fairness, first be offered the option of holding a general election to resolve any dispute over supply between the two houses and informed that if he did not agree to do so his commission would be withdrawn.”

Nathan says: “Mason was an excellent High Court judge, but privately advising Kerr was disgraceful.”

This shows Kerr was testing his options three weeks before he sacked Gough. On November 10, he received formal advice from High Court chief justice Sir Garfield Barwick (a former Liberal minister) on dismissing the PM.

Justice Howard Nathan: A story to tell.Credit: The Age

While the crisis dragged on, McLelland sent his cabinet adviser to Western Australia to try to dampen down an expected pay hike that would feed the inflation cycle.

“The Diamond sent me to Perth to try and hold it [the pay rise] back.”

It was Armistice Day – November 11 – and as a tactic to disturb the US company negotiators he called for everyone to stand for a minute’s silence at 11am. The silence was broken by a phone call from Canberra. It was Senator McClelland in Canberra at 2pm, ACT time.

“The Diamond said, ‘Guess what, Digger?’ (he always called me Digger). We’ve been sacked, and you’re a barrister again.”

Bob Hawke, Jim McClelland, Bill Hayden and Gough Whitlam in the grounds of the Lodge on November 12, 1975, the day after Whitlam’s dismissal.

McClelland, perhaps knowing he had been duped by a close friend and realising he had been used, refused to speak to Kerr again.

In a March 1991 ABC interview after Kerr’s death, the Diamond was as sharp as ever.

He said after the Dismissal he had nothing but “rage, hatred and contempt” for his former friend.

“I previously liked, admired and enjoyed his company. He was gregarious with a hedonistic streak.”

Kerr, he said, wanted to be accepted by the establishment, but after the sacking he was discarded.

“He was infatuated with power. He wallowed in Machiavellian.”

Loading

McClelland said after the Coalition won the 1975 election at the ministerial swearing in ceremony, Kerr had tried to justify his decision to sack Whitlam as the only way to break the deadlock.

He was told six conservative senators were about to cross the floor to pass the supply bill.

“He was intelligent enough to know he had made a mistake,” the former senator said. “We were great friends, but I could never forgive him.”

The Diamond left the Senate in 1978. He became the chief judge of the NSW Land and Environment Court and headed the 1984 Royal Commission into British nuclear tests in Australia.

He found prime minister Sir Robert Menzies had kept details of the tests from his cabinet and he did not seek independent advice about the potential hazards of the tests, instead accepting British safety assurances.

He died in 1999. Nathan says: “The Diamond was a marvellous man with a towering intellect.”