In 1975, Kelvin Templeton was an emerging teenage star footballer, who found himself without a dwelling after living with local, mainly elderly couples. One of them housed him in a backyard bungalow.

The Bulldogs, then known as Footscray, came up with an astonishing accommodation solution – they placed Templeton, then 18 and straight out of Traralgon in Gippsland, in the Maribyrnong Migrant Hostel, alongside refugees and other “displaced persons.”

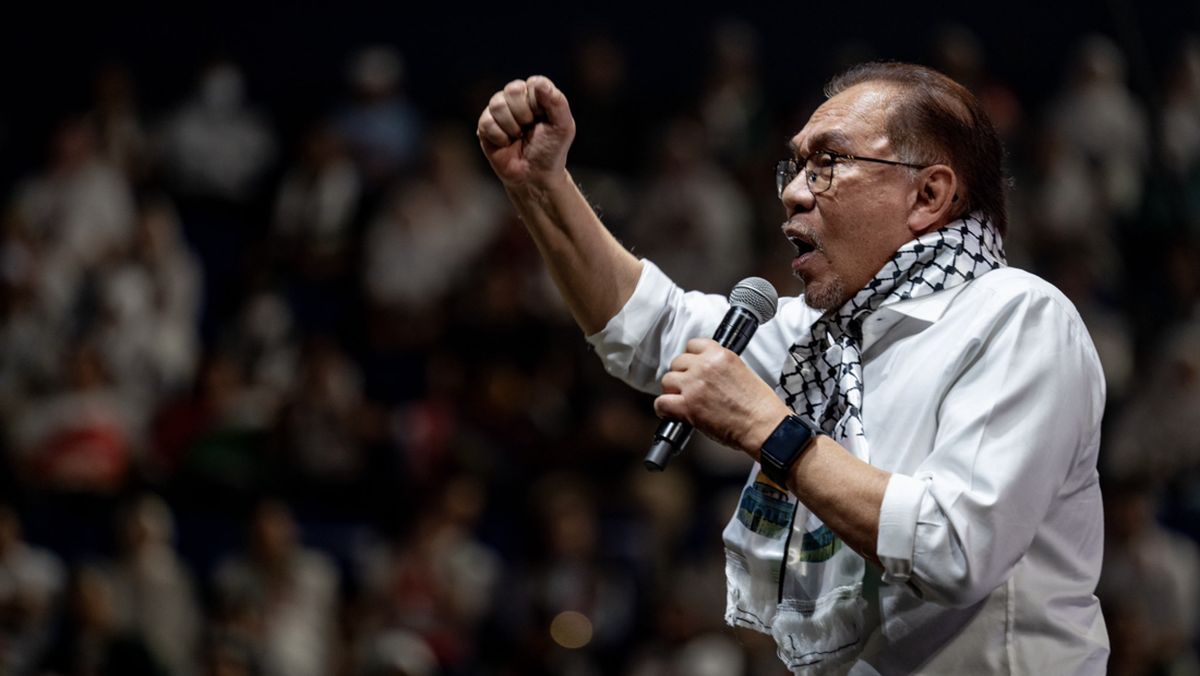

Former VFL champion Kelvin Templeton.Credit: Wayne Taylor

Templeton was the only Bulldogs player of that time to live in the migrant hostel, where he shared a floor with two other men, whom he guessed were central European.

“There was this really tiny sort of lounge room – it was a couple of chairs in it, that was about all,” he recalled of the migrant hostel, on the site of old explosives’ factory in Maribyrnong. “Off that were three doors, three bedrooms. I had one of them.”

He didn’t speak to two men on his floor. “We couldn’t converse, they didn’t speak English ... but I do remember going to the cafeteria.”

Former VFL champion Kelvin Templeton.Credit: The Age archives

Templeton, who was already a regular senior player – and one who would become a Brownlow and Coleman medallist – found himself using the migrant hostel as only a place to sleep and eat the bland dormitory food.

“I kept away. I only went there to sleep, had dinner and I tried to keep away from the place.”

He thinks he lived there for up to four months before finding his first “own” rental, a flat in Sunshine.

Templeton, 69, can’t recall if he even told his parents back home in the Latrobe Valley about his unusual lodging.

“I don’t know if I ever told them … I mean, I thought it was really odd. I wasn’t happy about it.”

Kelvin Templeton’s first novel.

Templeton’s recollections of that period are vivid, such as the drinking culture among players and the casual attitude to on-field violence.

“I had to think this through because you either portray as it actually was, be honest about it, or you fudge it...maybe people won’t like reading that because that’s the way things were, and that’s the way football was.”

Those staples of his era are depicted with unsparing detail in Templeton’s first novel, Collision, which travels back to that same year he lived in the migrant hostel, 1975, and tells the story of fictional young footy star, Joshua Shamrock, a goalkicker on track for greatness when he suffers a career-ending injury.

Templeton played in the 1975 game in which teammate and South Australian recruit Neil Sachse became a quadriplegic following an accidental collision with Fitzroy’s Kevin O’Keeffe; he also knew the story of Stephen Boyle, the Bulldog player who lost sight in one eye in a game against St Kilda (his son Timothy Boyle played for Hawthorn and wrote excellent columns for this masthead after retirement), and of Robert Rose, the brilliant cricketer-footballer (and son of Collingwood great Bobby Rose, who coached the Dogs from 1972-1975) who also became a severe quadriplegic, via a terrible car accident.

The story of Joshua Shamrock isn’t quite like that of Sachse, Rose or Boyle (the former pair having passed away), but Templeton – a goalkicker like Joshua – acknowledged that his knowledge of those cruelly cut-down players had informed his novel. “They’re an inspiration, in a way.”

Neil Sachse photographed in 2005.Credit: David Mariuz

So, in addition to being the only Brownlow medallist to be housed in a migrant hostel by his club, and one of the last key forwards (1980), we can safely assert that Templeton’s the only living Brownlow winner to have written a novel – as distinct from ghosted autobiographies, of which there are many.

“Really bad things could happen. It was a dangerous game,” he said of his period as a young player.

“I often say it was a very casual attitude to violence. So it’s not surprising that really bad things did happen, and they happened to those guys and it could’ve happened to me, it could’ve happened to any one players. It’s just luck.”

In Collision – published by Wilkinson Publishing – the story really unfolds once the protagonist recognises he won’t play league football again, and has to find a way to navigate adulthood once his childhood dream – really an extension of his childhood – is gone.

“All his eggs are in one basket from a really early age,” Templeton explains.

Loading

“The main theme that I wanted to play with is one of the oldest story arcs we have, which is the long path from loss to redemption.

“The main character really has to go through a journey of finding out who he is and work out, and develop some sense of his own identity.

“He tries to find his feet again.”

No spoilers here, except to say there’s a mystery subplot, and Shamrock’s story isn’t all despair. It should resonate with former players who struggled for an identity post-playing career, a problem probably more prevalent today, since footballers are well paid full-time professionals without day jobs.

Football features less in the second half of Collision, but Templeton’s descriptions of the old footy universe sprang from his varied experience in the game. He left the dysfunctional Dogs, crossing to Ron Barassi’s equally unsuccessful Melbourne, alongside another Brownlow medallist Peter Moore, in 1983 and later served as chief executive of the Sydney Swans (from 1995 until 2002) when the spell of Tony Lockett helped the code’s revival in NSW.

Kelvin Templeton flies high during his playing days.Credit: Photographic

“None of the facts which happened to this character had really anything to do with me,” he said, explaining that he had, of course, drawn on the emotions he had felt as a player. “He plays a great game, you know I can draw on how I felt.”

Templeton has borne his own personal catastrophe – the sudden death from a heart attack of his dear wife Kerry, in Abu Dhabi, when their daughters were nine and seven. This tragedy followed his stint as Swans CEO.

“It was catastrophic, absolutely catastrophic. She was 50 and the girls were nine and seven. I was establishing a new business in a foreign country. Catastrophic. And we ended up coming back to Australia.”

But Templeton and his daughters soon moved back to the UAE and spent six or seven years there, as he established a business that involved work for Sheikh Mansour’s sporting teams (which now include Manchester City).

Once back in the UAE, Templeton’s younger daughter Kiki asked her dad, “does this mean we’re not going to have fun any more?”

“I’ll never forget that statement. And I thought, ’right, I’m actually going to turn this situation around.” Templeton and his girls turned into avid travellers, hopping on planes to Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, Morocco and Jordan.

Loading

Previously a dabbler in painting and owner of an MBA from University of Technology Sydney, what on earth prompted the understated Templeton to write a novel?

“Because I’ve been an avid reader of fiction all my life ... if you’ve read as much as I have, at some stage you think, I’ll try it myself.”

Templeton says his literary models were Norwegian novelist Per Petterson, American James Salter and Richard Yates’ classic Revolutionary Road.

Collision was launched at an eclectic gathering that typified Templeton’s odd mix of arts, commerce and footy in South Yarra last Wednesday. Steven Smith, the incoming president of Melbourne and an old teammate, spoke affectionately about Templeton to a crowd that counted two other Brownlow medallists, Moore and Gerard Healy, former Bulldogs and a woman who helped shepherd the novel into existence, legendary Australian publisher Hilary McPhee.

It was a collision, if you like, of the strands of Kelvin Templeton’s unusual life.

Keep up to date with the best AFL coverage in the country. Sign up for the Real Footy newsletter.

Most Viewed in Sport

Loading