Moments before Mercury “Merc” Psillakis died at Dee Why beach on Saturday morning he warned surfers in the water with him of the presence of a shark, calling on them to group together.

“He was aware of the risks of the ocean and while he loved surfing, he was always vigilant about keeping himself safe,” said his family in a statement released to the media on Tuesday.

Scientists with the NSW Department of Primary Industry have now confirmed they believe the shark that took Psillakis to have been a great white of around 3.5 metres in length, suggesting the animal, which was not tagged, is probably an adolescent.

Maria and Mercury Psillakis and daughter Freedom (centre).Credit: Courtesy of the Psillakis family

As the family released their statement, thanking fellow surfers who helped recover Merc from the water, as well the Life Saving Club, emergency services, police and the broader community that has provided support since, DPI staff and contractors continued their work tracking and monitoring potentially dangerous sharks in NSW waters.

Each day 300 “smart” drum lines are set at 20 locations 500 metres off beaches on the NSW coast, baited with hooks targeting potentially dangerous sharks. When an animal is hooked an electronic notification is sent to contractors, whose job is to reach the shark within 30 minutes.

Target sharks – great whites, tiger and bull sharks – are swabbed for tests on their recent diet, tagged, and released a kilometre out to sea.

“Our research shows they’ve got a fight or flight response,” explains Dr Paul Butcher, the department’s principal research scientist.

“So they’re often 15 to 20 kilometres offshore within the next 24 hours after release. All the other shark species, the little whalers, the duskies, the sandbars, the black tips, are all released on site.”

The department’s drum line program has now gathered one of the largest databases on the behaviour of its target species on earth. Much of the information it gathers on potentially dangerous sharks is made available in near real time via the government’s SharkSmart app and website.

Locals pay tribute to Mercury Psillakis at Dee Why Beach.Credit: Danielle Smith

The app showed that on Tuesday target sharks were active all around Sydney. At 12.31am, a great white identified as shark #2361, which had been caught and tagged at Evans Head in August, was detected by a receiver at Avoca Beach. At 1.07am, another white that had been tagged in Newcastle in November alerted a receiver at Hawks Nest.

Throughout the day, the system kept sharing its alerts. A white tagged in Terrigal last June visited Killcare after 1am, while another that had last been detected at Forster in October was pinged at Maroubra at 5.07am, half an hour before dawn. At 8.40am, a drum line signalled to contractors that a tiger shark had been caught at Port Macquarie. They tagged and released the 2.44 metre long animal. An hour later a 3.93 metre tiger was released at Gerringong, followed by a 2.63 metre white shark at Coffs Harbour.

So far, says Butcher, more than 300,000 people have downloaded the app, and the system has detected tagged animals around 400,000 times.

The system shows that white sharks are particularly active in NSW waters at this time of year and many will return to Victoria as the waters warm towards summer. This is when the receivers will start to detect an uptick in bull shark movements as they move south from Queensland.

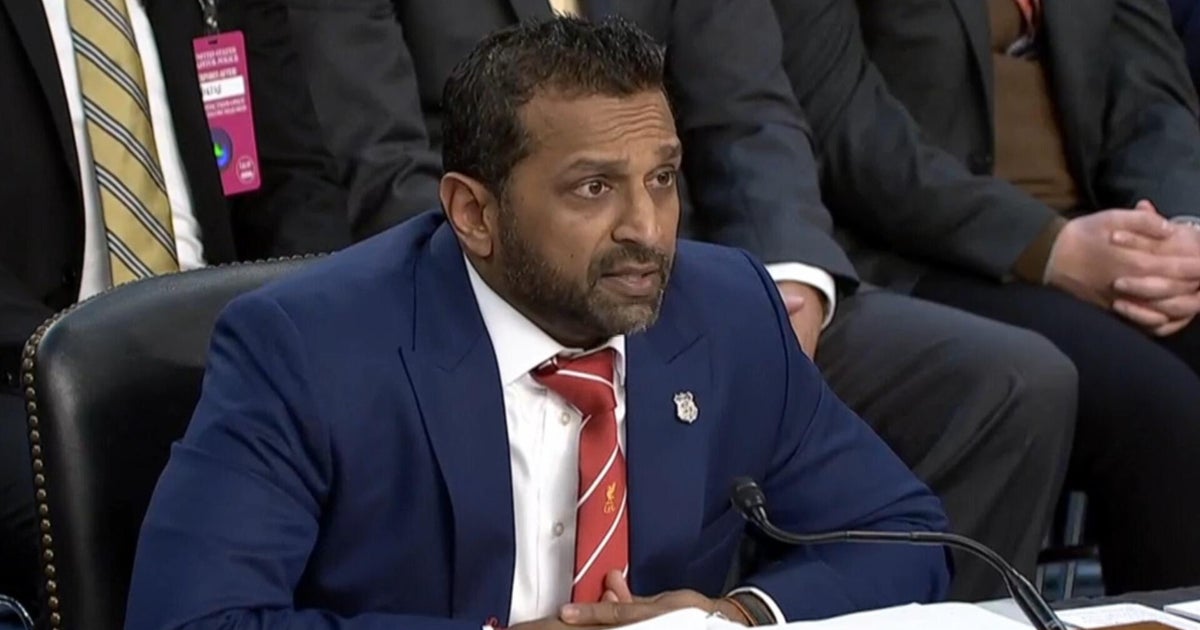

A shark being tagged and checked by DPI after being caught on a drum line.

It also shows, says Butcher, that despite the tragedy that unfolded at Dee Why on Saturday, the target sharks overwhelmingly ignore the human swimmers they regularly come across as they travel the coastline.

Anyone who regularly swims at Sydney beaches is likely to unknowingly swim alongside these animals, he says.

“We’re currently writing up some research about using our video from drones and also citizen science to show that white sharks and other sharks are swimming past us more often than what we actually think,” says Butcher.

“We know that they swim at sort of three to five kilometres an hour. They swim just outside the wave break at the back of the beach, and they’re really inquisitive, especially white sharks. They’ll have a look at a bit of plastic or a bit of seaweed in the water, but they’ll certainly swim in straight lines along those beaches and they won’t do laps around and around and around, they keep on moving up and down the coastline.”

Mouth swabs show the sharks tend to prefer benthic animals – those that live on or near the seafloor, like stingrays and mullet, Butcher says. Most tagged around the NSW coast tend to be juveniles or sub-adults, ranging in size from around 1.5 metres to 4 metres.

A statement from the NSW Minister for Agriculture said the government would halt its trial of removing shark nets following the recent incident until after the summer.

Dee Why had a net in place when Mercury was attacked.

In its statement on Tuesday, the Psillakisis’s family said Mercury loved the ocean and was deeply connected to the community of surfers.

“Unfortunately, this was a tragic and unavoidable accident.”

Most Viewed in National

Loading