For lunch, Connell orders eggs Benedict. I opt for the roast pumpkin tart before asking my lunch guest more about how she ended up catching some exciting breaks on what she describes as scholarly “waves”.

Connell chose eggs Benedict for lunch.Credit: James Brickwood

“Real research is a collective process,” she says. “It is very rarely a matter of individuals making sudden breakthroughs – that can happen, like Einstein in 1905 – but mostly it’s much more collective than that. I write books, and they come out under my name, but there’s a wadge of source material that I’m building on – hundreds of other researchers might have built up that area.”

During the 1980s, as social attitudes to women shifted and economies were transformed by a surge in female workforce participation, Connell published groundbreaking work on gender and power.

“I began thinking about gender as a large-scale social structure in a similar way that myself and others were thinking about social class. Of course, they differed in many ways but we argued that both gender and class were large-scale, powerful social patterns,” she says.

“But another reason I became interested in gender relations was an issue in my own life. The question of where I belonged in the gender order, as I later called it, has been with me from childhood on. So there was an intellectual and a personal issue.”

Connell is perhaps best-known outside Australia for her work on the social construction of masculinity; she is credited with pioneering that particular field of academic inquiry that has flourished since the release of her book Masculinities in 1995.

In it she argued there is not “one” masculinity but many different masculinities. The book draws on extensive interviews with four different groups of men all undergoing different experiences of change – some of them working to transform gender relations, and some resisting it.

“I’d been working on masculinities for more than 10 years when that book came out,” she said. “It had the role of bringing the field together and offering a kind of synthesis of work that had been done.”

The field work for Masculinities was funded by the Australian Research Grants Committee (now the Australian Research Council). Before any findings were even published, the project was attacked for being a conspicuous waste of taxpayer funds by the federal “Wastewatch Committee” of the opposition Liberal and National parties.

Despite those objections the research went on to have lasting global influence; it triggered a flood of research and policy debate in many nations.

The roast pumpkin tart at Sideways Deli Cafe.Credit: James Brickwood

Masculinities was subsequently voted one of the 10 most influential books in Australian sociology and has been translated into a dozen languages. After it, Connell was asked to be an adviser to various United Nations agencies and lead international programs about men, boys and masculinities, gender equality and peacemaking.

“One thing that really pleased me about this stuff was that it did turn out to be useful to groups of teachers who were teaching boys, to people in the health sector dealing with men’s health issues, and to counsellors, and so on,” she says. “There has been a real practical pay-off.”

Masculinities has been referenced more than 32,000 times in academic works, according to Google Scholar, which tracks citations. As a point of comparison, Germaine Greer’s feminist classic The Female Eunuch has about 4100 citations.

By chance, I hear tangible testimony to the influence of Connell’s work a few days after our lunch; a social-worker friend tells me he loved reading Masculinities. “That book had a big impact on me and shaped the way I work, especially with young men,” he says. “It was like a breath of fresh air.”

Connell again sparked international academic debate in 2007 with her book Southern Theory, which called out a “northern bias” (read: the US and Europe) in the world of social science and argued for greater recognition of contributions to the discipline made outside Europe and North America.

Connell went to school in Sydney but did her undergraduate studies at Melbourne University and then a PhD at Sydney University in the late 1960s. She began working as an academic in the early 1970s when the university sector was expanding rapidly in Australia.

“I was incredibly lucky, there was a massive need for more staff and I got a job without hardly even looking for it,” she says.

Connell went on to work at several universities in Australia and abroad, including being the founding chair of sociology at Macquarie University. She is now professor emerita in social science at Sydney University.

Recently Connell has turned her research attention to the sector she has been part of for six decades: higher education. Her 2019 book The Good University investigates the dramatic change in tertiary institutions during the past few decades and the acute challenges they now face.

This week she will deliver Sydney University’s annual Wheelwright Memorial Lecture, which also marks 50 years since subjects in the discipline of political economy were offered there; political economy courses offer an alternative to mainstream economics, and the prime minister, Anthony Albanese, is a former PE student. The lecture is titled Should We Abolish Universities?

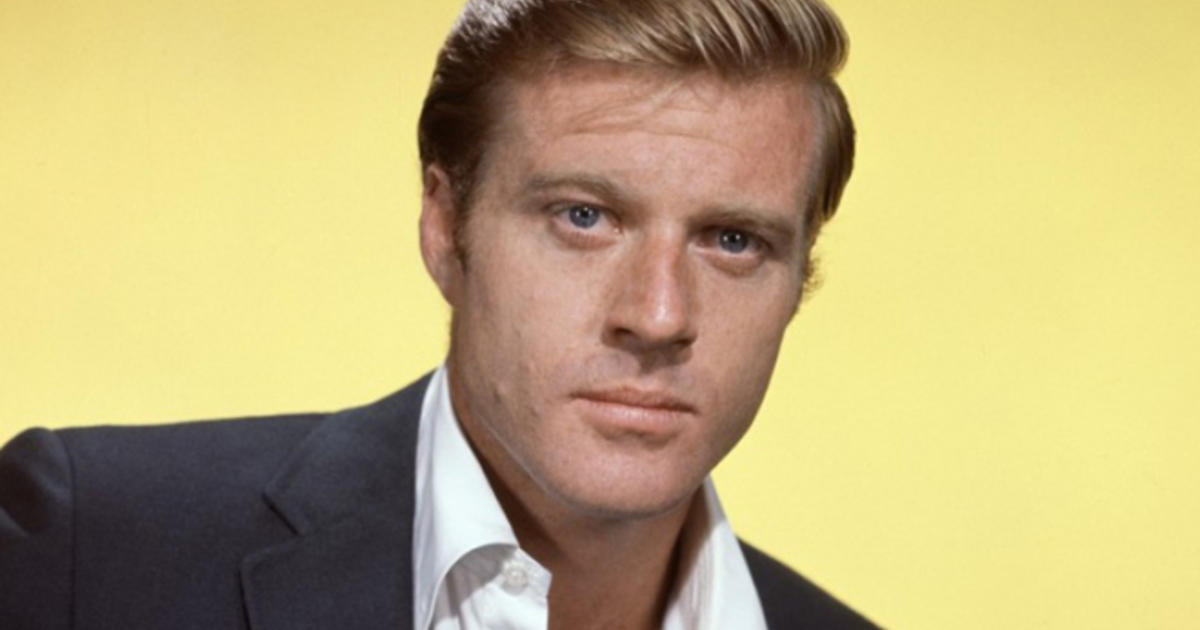

Professor Raewyn Connell.Credit: James Brickwood

Connell says the introduction of university tuition fees, part of the Hawke government reforms aiming to expand the university sector made during the 1980s along with corporate-style management, have created a contradiction in the sector. “As universities became more and more like profit-making corporations and, indeed, more and more of them actually were profit-making corporations, a conflict opened up between that way of organising the institution and the actual nature of teaching and research.”

Connell says this shift has made it harder to teach well and do high-quality research. “Academic work, the actual daily labour, has also become more like work in a for-profit corporation, too. It’s now less free-floating and self-directed, more something done under management control,” she says.

Our conversation is interrupted by Connell’s smartwatch. “I hate it,” she says, scowling at her wrist. “But it does remind me of things, and it has a safety mechanism. Since I’m now in my 80s I guess that matters.”

Connell recommends the apple pie, a Sideways Deli Cafe speciality, and when the desserts and coffee arrive our conversation turns to Connell’s next book: a very personal project called Trans Lives.

In it she explores the social forces shaping trans women and men and the varied lives of trans people across the globe.

“Gender changes take different shapes in different parts of the world,” she says. “I’m trying to think that through from a point of view that takes the issues of everyday life of trans women and men into account, that doesn’t think of gender transitions or trans existence as an airy-fairy thing in people’s heads but as something that affects their wellbeing in the world and their chances of living a long life.”

She has met with trans groups “large and small” in 10 different countries and was struck by the short life-expectancy of trans people in many parts of the world. “In some groups I met it would be rare to find a trans person over the age of 40,” she says. “I was double the age of the groups I was talking to.”

She attributes shortened lives to the violence, stress, poor health and housing, and general deprivation experienced by many trans groups.

The bill.Credit: Matt Wade

The book addresses trans issues “not much talked about” like the economics of trans life and the variety of trans cultures and traditions that exist across different nations. One example is the Hijra community in India, a transgender group that has been part of the subcontinent’s complex cultural mix for hundreds of years.

Connell has been tracking what she describes as a set of international anti-trans campaigns that have greatly intensified since about 2015.

“I think you can show how particular anti-trans campaigns heated up about that time, notably in the British media,” she says. “Then came the weird ‘bathroom wars’ in some states of the US, which are still going strong. The Russians got into the act around 2022 and passed a really vicious anti-trans act in 2023. Those are among the markers of this backlash.”

So what triggered this reaction? “Behind this persecution are the broad and deep changes in gender relations over the last two generations,” says Connell. “Greater economic and social freedoms for women, the advance of girls’ and women’s education, and the advance of LGBT rights including marriage equality, have disturbed older patterns of privilege.”

Loading

For those with a “reactionary agenda in gender politics”, who have failed to prevent these changes and fear more, trans groups make a vulnerable target.

“Trans are the next group in line, so to speak, for political and cultural forces wanting to turn the clock back on sexual and gender politics,” she says.

Connell hopes her new book will help people get a more “understanding and accurate idea of what transition involves”.

As we prepare to leave after paying the lunch bill, I check with Connell how long she had worked on Trans Lives. “My whole life,” she says with a grin.

Professor Raewyn Connell will deliver the E.L. ‘Ted’ Wheelwright Memorial Lecture at Sydney University on September 10 at 6pm.

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.