For most of his adult life, my father was a timber worker on the NSW north coast, mostly in the sawmills of the Manning and Hastings valleys.

He would often remark that there was no future in forestry. But on Sunday we saw an announcement that will bring real jobs back to the forests. Only now, the work will revolve around repairing nature, restoring wildlife and protecting against catastrophic bushfires.

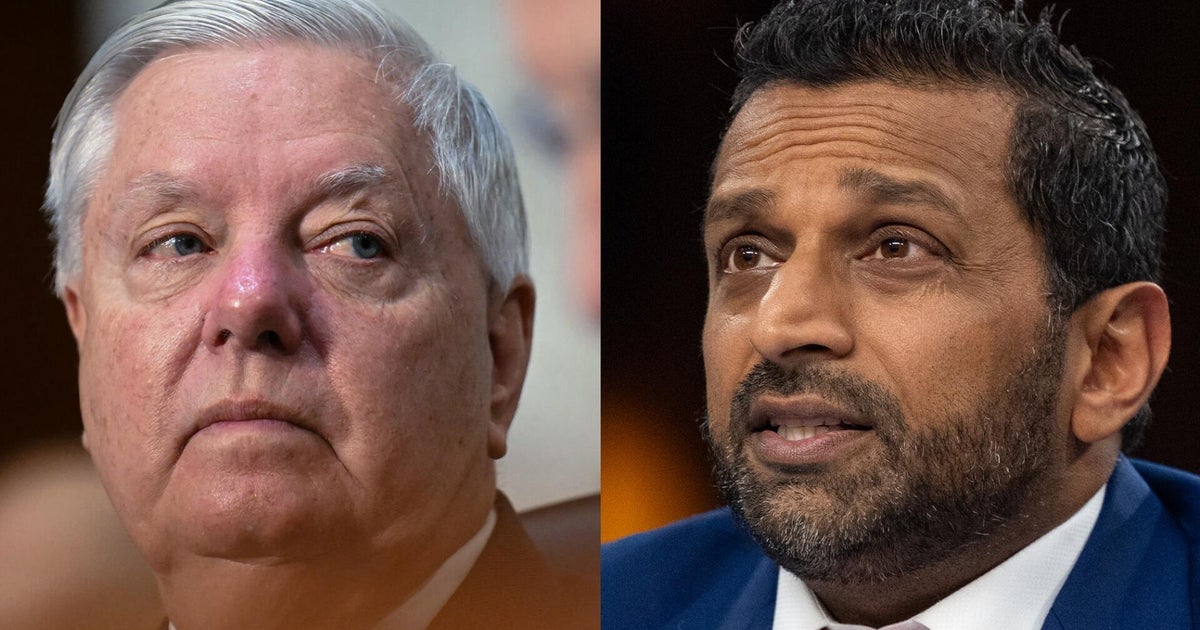

Spanning 176,000 hectares of public native forests, the Great Koala National Park will provide a home to up to 20 per cent of NSW’s remaining wild koalas.Credit:

The case to reconstruct the forestry industry is undeniable. Across the road from our family home in Taree was a sawmill. There were two others in walking distance, and a dozen more a short drive away. Today, only two of those 15 sawmills remain. And the forests themselves are smaller, shorter, younger and less biodiverse. They are also drier and at far greater risk of catastrophic bushfires.

Unsurprisingly, the native forest logging industry in NSW is now on life support. If it wasn’t for NSW taxpayers, there wouldn’t be a pulse. Over the past four years, taxpayers footed a bill of $73 million to cover the industry’s losses while stumping up an additional $127 million to keep basic native forest logging operations going.

The sun rises over the future Great Koala National Park, as seen from Point Lookout in the New England National Park.Credit: Janie Barrett

Even with the purse of the state’s taxpayers, native forest logging hasn’t guaranteed secure jobs for regional workers. There wasn’t a week that went by where my father didn’t fear losing his job – either to the dangers of the chainsaw or the dwindling quality of timber harvested from the forests.

Today, just 10 per cent of the timber taken from Australia’s native forests ever reaches a sawmill. Three times as much is used as firewood. Five times as much turned into woodchips, and the rest is pulped. What is left of the high-quality hardwood in our forests is becoming increasingly rare to find. So, too, the commercial demand for it. Australia’s construction sector has moved on, primarily shifting to reliable softwood. The timber that builds our houses today doesn’t come from native forest but is sourced from plantations and forged by engineered wood products.

All vital signs suggest that native forest logging in NSW is a sunset industry. It’s a reality that regional NSW has long known, yearning for a viable alternative rather than clinging on to a failing model they know must collapse.

Sunday’s announcement of the Great Koala National Park (GKNP) offers the first credible plan for the future of NSW’s public native forests. Spanning 176,000 hectares of public native forests, the GKNP will provide a home to up to 20 per cent of NSW’s remaining wild koalas.

Recent polling has shown 70 per cent of voters in Coffs Harbour support this park and the cessation of logging within it. In a region reeling from natural disasters, local businesses see the Great Koala National Park as a boon for tourism, according to an open letter to Premier Chris Minns penned from 100 Mid North Coast businesses. Will the GKNP register like Bondi? The Blue Mountains? The Great Barrier Reef? We’ll find out in time. But the park can guarantee something far more tangible for workers on the Mid North Coast.

Loading

In halting logging within the park boundaries, the NSW government has the opportunity to implement the Improved Native Forest Management (INFM) carbon method, which will fund the park and its management through revenue derived from high-integrity carbon credits.

Federal Climate and Energy Minister Chris Bowen foreshadowed INFM for the generation of Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs). The finer details of the method are still being assessed for final approval by the Commonwealth parliament, but its use in the native forest estate could see the negative value-in-use of logging replaced by a highly profitable operation based on the sequestration of carbon, nature repair and the protection of habitat for native fauna, including the koala and greater glider.

According to independent economic analysis, this method can generate about $100 million a year, for 15 years, when applied across NSW. That would create about 1700 permanent jobs in regional NSW – managing native forests, not cutting them down.

These jobs aren’t seasonal. Neither are they insecure. They are permanent jobs in forest management, hazard reduction and habitat restoration. Many of these jobs build on existing skills of loggers and are designed for the long haul. Importantly, they don’t rely on the generosity of the taxpayer for funding. This method makes the park financially self-sustainable.

Loading

At present, natural disaster relief in NSW is underfunded and competes with other vital services for state budget resourcing. For a region that’s suffered floods, storms and fires in recent years, the Mid North Coast of NSW knows too well the need for better-resourced forest management.

Now Canberra needs to get on board. The NSW government submitted the INFM carbon method to the Commonwealth for federal approval. Senators and members of parliament have the chance to support it. But the longer they wait, the longer the regions go without reliable jobs, restoring nature and protecting against bushfires.

A career managing native forests for carbon and biodiversity wasn’t a future my father imagined. But it would have given his family a better standard of living, and a more secure one.

Dr Ken Henry is an economist who served as Australia’s Treasury secretary from 2001 to 2011. He is chair of the Australian Climate and Biodiversity Foundation.

Most Viewed in Environment

Loading