Opinion

October 10, 2025 — 7.58pm

October 10, 2025 — 7.58pm

“It has to be hospital, I’m afraid” are never the words you want to hear, particularly when you are caring for an elderly relative.

One in five hospital beds are currently occupied by an elderly person. Credit: Getty Images

A few weeks ago, after hearing that dreaded phrase, my 92-year-old mum and I spent a night in Ryde Hospital emergency. Other nearby hospitals had no room at the inn, or the parking bays for their ambulances. Six hours after we called for help and four hours after the divine duo delivered us into the hands of the wise medical staff, we saw an exhausted doctor.

The little suburban hospital was heaving. It was also clearly in desperate need of a rebuild, which is, thank god and thank government, under way. It would be charitable to call the walls grimy, everyone in the waiting room had the look of cattle, with eyes downcast in resignation, and the man in the cubicle next to us was lowing every minute (if lowing is a cross between a low groan and a deep scream).

My mum got a bed in a curtained ward, and the medicine she needed by midnight. By then we were both exhausted and emotionally wrung out.

The next day, after more wise men visited and tests were done, she was allowed to go back to her aged care facility to be looked after by the resident GP and nursing staff.

Loading

We were lucky. I’m a member of the “sandwich generation”, who no longer talk about our kids at dinner parties but instead swap elder emergency stories. One friend’s dad has gone to hospital by ambulance four times in the past six months to treat chronic infections. Another is now on first-name basis with several staff at a huge hospital as his mum has had so many falls.

As my mum and I both recovered from the ordeal, I vowed to make use of a private clinic next time (dinner party competitions always end with this advice). However, I’m aware that the elderly and the infants who we once talked about have a lot in common – they need walking aids to toddle, they like to read out every street sign and they usually get sick on weekends after 6pm.

What they don’t have in common is that older patients usually have much more complex problems and are often in hospital for much longer. And a lot of them don’t want to be there at all.

As the Herald pointed out this week, up to one in five beds in some NSW hospitals are occupied by elderly patients. It’s leading to confusion for the frail, and concern for their middle-aged children, and it is causing delays through the system. NSW Health Minister Ryan Park is acutely aware of this in his electorate in Shoalhaven.

In federal MP Mike Freelander’s Campbelltown electorate, the numbers are not that different. A paediatrician and co-chair of the Parliamentary Friends of Aged Care, Freelander says the needs of the elderly affect even the youngest patients he looks after. He points to an ageing population, difficulties in building aged care facilities, and workforce issues with in-home aged care. This means people get parked in hospital when they need to move to a care facility. GP shortages don’t help.

But we ain’t seen nothing yet – because the Baby Boomers are ageing in a big bubble and they will need more care as they do so, as is their tax-paying right.

Freelander says the system is also a victim of its own success.

Medical staff are getting better at dealing with acute and complex cases that are the gift of old age. As we admit patients with more complicated needs, they require longer hospital stays. My dad, a former doctor, knew this himself. He never wanted to go to hospital until he had to, and that’s where he died.

Professor Ken Hillman has been telling anyone who will listen about this for years. He wrote about the “conveyor belt of care” that’s often inconsistent with the wishes of many elderly patients in the Internal Medicine Journal last year.

Loading

He and his fellow researchers argue this is “the major contributor to the so-called hospital crisis, including decreased capacity of hospitals, reduced ability to conduct elective surgery, increased attendances at emergency departments and ambulance ramping”.

He suggests more detailed goals-of-care discussions and shared decision-making, rather than simply completing Advance Care Directive documents.

Freelander says that “many families struggle to understand what is happening in hospitals, how much we can do and how to be prepared to make decisions”. He worries about many who don’t have a regular GP and an electronic record of their wishes.

“We need much more help for families to prepare and plan for hospital admissions of the elderly.”

He’s so right because when the ambulance has been called and you’re on the conveyor belt of care, tired, hungry, stressed and frustrated like I was a fortnight ago, you often can’t think clearly. Families also need to plan earlier for aged care, so it doesn’t take an emergency to lead to a room scramble and a long wait in hospital.

There will always be situations we can’t prepare for, and Mum and I may yet again end up fatigued under fluorescent lights for hours on end. I’m thankful we will get care and for the staff who will help us. But we all have a role to play to unclog the system.

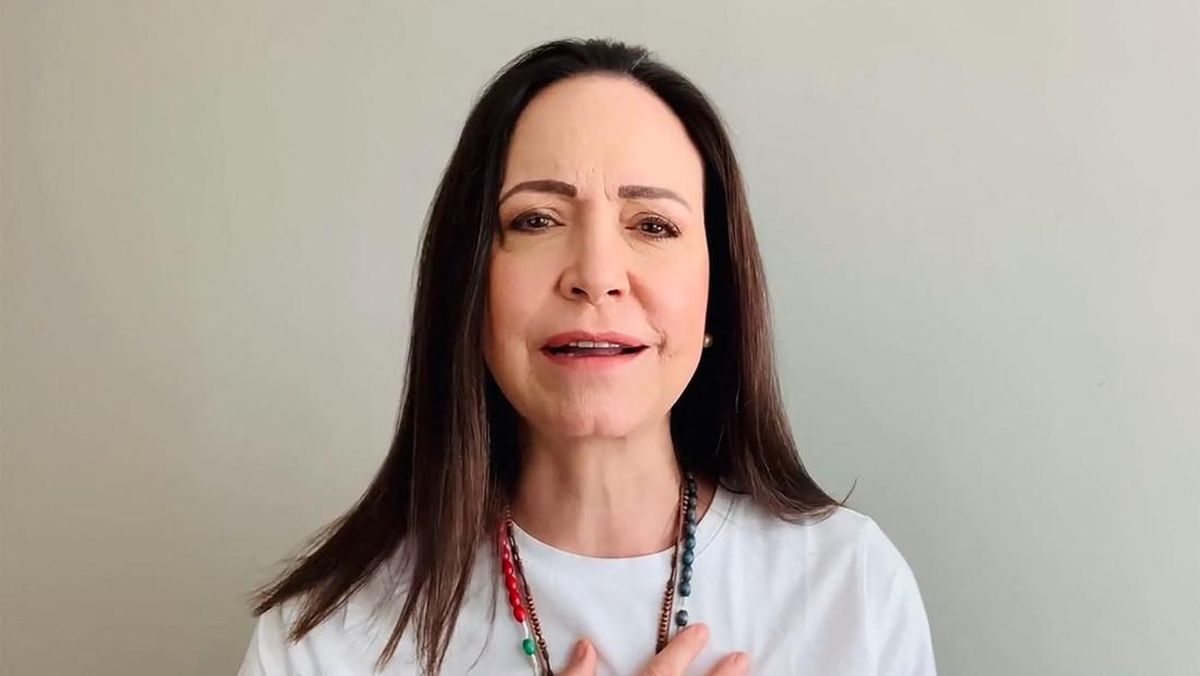

Sarah Macdonald is a broadcaster, writer and ambassador for Violet, a not-for-profit organisation that advises people on how to manage the later stages of life.

Get a weekly wrap of views that will challenge, champion and inform your own. Sign up for our Opinion newsletter.

Most Viewed in National

Loading