John Drysdale had done everything right as the devastating Longwood bushfire swept towards his property just outside Yarck amid the nightmare conditions of January 9.

The farmer lived through two of the state’s worst catastrophes – Ash Wednesday in 1983 and 2009’s Black Saturday – had been reducing fuel loads around his house and sheds, ploughed fire breaks through the property and had sprinklers primed and ready.

But when the fire – fanned by the winds that howled in from the north – swept toward the house and threatened to ignite the pine trees behind it, Drysdale, a 30-year-Country Fire Authority veteran, knew it was a fight he would not win.

Yarck farmer John Drysdale, who lost his home to the Longwood bushfire on January 9.Credit: Photograph by Chris Hopkins

“I’d set it all up, and I was going to [stay and defend],” Drysdale told this masthead.

“It was getting late, I’d turned all the sprinklers on, had them all going. But then I just said, ‘it’d be stupid to stay’.”

As he continued to assess the losses this week – which includes hundreds of sheep, the house, sheds, seven motorbikes and three cars – Drysdale was philosophical.

There had been plenty of fires in the nearly 150 years his family had occupied the site. With four children and 13 grandchildren living nearby, this blaze would not be forcing them off the land.

“We’ll build something,” Drysdale said. “It won’t be the same, but we’ll build something.

“They [the family] all get together here, and we’ve got to have somewhere where we’ve we can look after everybody.”

John Drysdale’s home was consumed by the Longwood blaze.

University of NSW bushfire behaviour expert Professor Jason Sharples said more and more Australians would find themselves in Drysdale’s predicament of facing bushfires that cannot be fought.

He said that although Australia had always known unstoppable bushfires, the conditions that tip fires over the threshold where they can no longer be fought are now far more prevalent.

That tragic realisation arrived on February 7, 2009, when 173 Victorians lost their lives in bushfires nobody stood a chance of stopping.

Before Black Saturday, Australia’s fire danger rating system had used a risk assessment scale of 100, based on the experiences from the 1939 Black Friday fires – the worst conditions recorded to that stage.

But Black Saturday shattered those limits with conditions well off the known scale, requiring a new rating of “catastrophic” – where the danger posed can no longer be measured.

“After Black Saturday was an acknowledgement that when it gets to those sorts of conditions, we can’t rely on the knowledge that we have, and we don’t know how fire is going to behave ... So in those sorts of scenarios, it’s just better to get out,” Sharples said.

“In the fire services, there’s been that acknowledgement for quite a while now that there’s just some fires that you can’t stop and your best option might be to just pick a house and try and defend it the best you can, rather than trying to stop the fire.”

On January 7, authorities were warning conditions were heading towards catastrophic.

As high winds ripped through the Alpine areas, as well as the rest of the state, the temperature in Longwood was 41 degrees.

The fire ignited just before 2.30pm on a nondescript section of the Hume Freeway just north of Teneriffe National Park.

Few of those living in its path, or even the fire services, had any chance of stopping it.

Winemaker and farmer Grant Taresch and his family were among the first to be hit.

The family were on holiday in Harrietville when they first heard reports of fire near their two properties.

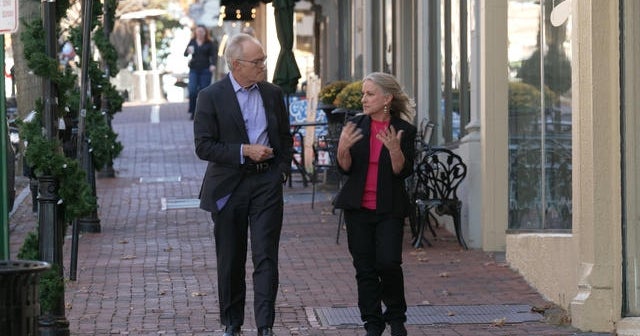

Grant and Suzanne Taresch with kids Isabella, Georgia, Heidi and Daniel at their property in Upton. Credit: Photograph by Chris Hopkins

But before Taresch could get home, the fire had leapt the freeway and all but consumed Elgo, the 740 hectare winery where he had been raising vines for 30 years.

“I raced around and did what I could, which wasn’t much,” said Taresch, who lost two houses on the Elgo property, 30 hectares of vines and up to 1000 sheep.

“It looked like a scene from Apocalypse Now, with four, five water bombers and 30 or 40 [fire] trucks, it was just an unbelievable effort, they saved a lot of infrastructure.”

On the neighbouring property a few kilometres to the south-west, where Taresch and his family live, he spent the night preparing the family home and another house for what turned into an epic two-day struggle.

The main fire front went through the winery’s properties in “about five minutes” Taresch recalls, but the spot fires, ember attacks and changes of wind direction did not relent for more than 24 hours.

“I was on my own, which was hard because I was trying to watch two houses and a wool shed,” the 56-year-old said.

To complicate matters, he said, “A few times the fire would burn through the poly fittings near the pump, and I’d lose [hose] pressure so then I’d have to go and fix those fittings. It was a nightmare.”

They also had a number of 44 gallon oil drums explode. But the house, outbuildings machinery and pets were all saved.

“I was lucky. We had water, plus I had a backhoe and an excavator.”

Ultimately, Taresch was able to save the two houses, wool sheds, six dogs and two cats at the family’s home property.

Many people living in rural areas across the country are well-placed to withstand severe fires like Longwood, Sharples said.

“If you’ve lived on the land for a long time, you’ve seen fires, then you also get a bit of an appreciation for what’s required,” he said.

“But, even so, if we talk about 30, 40, 50 years ago, when a fire did come through, there was a high chance it was going to be on the scale that you could do something about, and you could actively and effectively protect your property.

“Whereas, as the conditions for unstoppable fires become more prevalent, there’s less chance that when you get hit by a fire it’s going to be something you can actually deal with safely.”

For the less experienced and prepared – tree-changers, hobby farmers or people on smaller properties without dedicated firefighting equipment – Sharples said certain areas will no longer be a choice unless owners have very deep pockets to fire-proof homes and rising insurance fees that are out of reach to most.

“If you can afford the insurance then sure, go and live in the bush. But I just don’t think that’s going to be a viable thing for most people in some areas.”

Victoria’s weather on January 7, 8 and 9 brought exactly the conditions Sharples has in mind for unstoppable fires.

A severe and unstable air mass hung over the state, fuelling winds that would gust at 100km/h in places, and with temperatures above 40 degrees in the state’s North Central district.

There was a build-up of long grass near the Hume Freeway and high fuel loads throughout the state after heavy spring rainfall.

A series of hot days had dried out the vegetation and turned much of the bush into tinder by that Wednesday afternoon.

Then, authorities suspect, a semi-trailer travelling along the freeway threw sparks into scrub on the Hume’s median strip about 300 metres north of Oak Valley Road in Longwood East.

The catastrophic conditions meant the resulting fire had every chance of becoming unstoppable.

Dozens of CFA tankers and crews first fought the fire at Longwood East into Thursday, January 8. But pushed by ferocious winds that limited support from water bombing aircraft, the blaze was too intense to be stopped.

Some crews pulled back to Ruffy to try to stop the fire there, but when it continued to overtake them, they retreated to Terip Terip and again tried to hold a line during a 30-hour stint for desperate local volunteers.

Loading

From Friday morning, CFA crews patrolled between Yarck and Merton to prevent the fire crossing the Maroondah Highway, where it would threaten more towns. Still, the catastrophic conditions were too intense, and the flames jumped the highway.

Dozens of firefighting crews pulled back to towns including Alexandra in a bid to protect as many homes and businesses as they could, aware the fire was unstoppable under the conditions in the wider bushland and farming areas.

After saving the majority of the town dwellings and businesses in the evening, firefighters were exhausted but continued to work through another a sleepless night.

Their big fear was that the fire could reach the Strathbogie Ranges, where the dense state forests, steep terrain and a westerly wind might catapult the blaze further east, where it could easily jump Lake Eildon to endanger Bonnie Doon and Mansfield.

But Saturday morning brought eased conditions.

Temperatures cooled and the winds dropped, allowing water-bombing aircraft to target areas of the blaze between Merton and Bonnie Doon.

Strike teams on the ground could directly attack the fire front, preventing the flames from crossing the Maroondah Highway towards the ranges.

After nearly three days, the fire had become stoppable.

But one life, that of Terip Terip cattle farmer Maxwell Hobson, had been lost, as well as 173 homes, countless livestock and 442 outbuildings.

The fire has still not been completely extinguished, with a watch-and-act warning still in place on Friday for many parts of the affected areas.

The destruction of machinery, vehicles, tools, fences and other farming infrastructure across the 136,000 hectares burned cannot be determined, but authorities and locals estimate the recovery will take years.

The choice for residents – to stay and defend or leave early – is not going to get easier, either, according to future fire risk researcher Associate Professor Hamish Clarke from the University of Melbourne.

“A lot of people are well-prepared and do want to defend their property. And if you defend your property, you can have a greater chance of saving it,” Clarke said.

“But unfortunately, there’s a greater chance of being in harm’s way too, so it’s a really difficult calculus.

“Sometimes the people who are most prepared can be at most at risk because we just don’t know exactly how extreme a fire is going to be.”

The extreme weather which propelled the Longwood fire is becoming more likely in some areas, and Clarke said climate change was “loading the dice”.

“Fires are changing, but it’s actually really hard to pin down how because they’re such complex beasts and there’s so many different drivers,” Clarke said.

While climate change might be making the area more prone to increasingly dangerous fires, the desire to live in the bush is not cooling.

Since the Ash Wednesday fires in 1983, the populations of the now Strathbogie and Murrindindi shires have increased by about 50 per cent, while Mansfield’s population has doubled, and that of the Mitchell Shire has boomed by about 250 per cent.

Property sales data shows median sale prices more than doubled over the past decade in all four shires hit by the Longwood fires, and clearance rates have remained strong before and after the 2020 bushfires.

The risks may be increasing, but they show no sign of dampening the attraction of life in the beautiful high country.

Clarke says a balance needs to be struck between evaluating the danger, better building and planning for bushfire resistant homes and towns, as well as evolving messaging to prepare people for the increasing reality of unstoppable fires.

“Ultimately, these aren’t purely scientific questions. We can try and help paint a picture of what’s going on, but it comes down to human values. And I guess a lot of people like living in areas that unfortunately are prone to hazards,” he said.