After 2½ years of living and working overseas, mostly in South America, there was so much I’d missed: safety, familiarity, public pools, people chirping “too easy!” upon conquering mediocre things. Then something confronting started happening.

I felt a weird cognitive dissonance: I was genuinely happy – relieved, even – to be back somewhere so comparatively stable economically, politically and socially.

But that very familiarity caused me to freeze for my first few weeks back. I couldn’t focus on work, opening 750 letters or even unpacking. I just gazed at the overflowing suitcase I’d two weeks prior moaned about living out of.

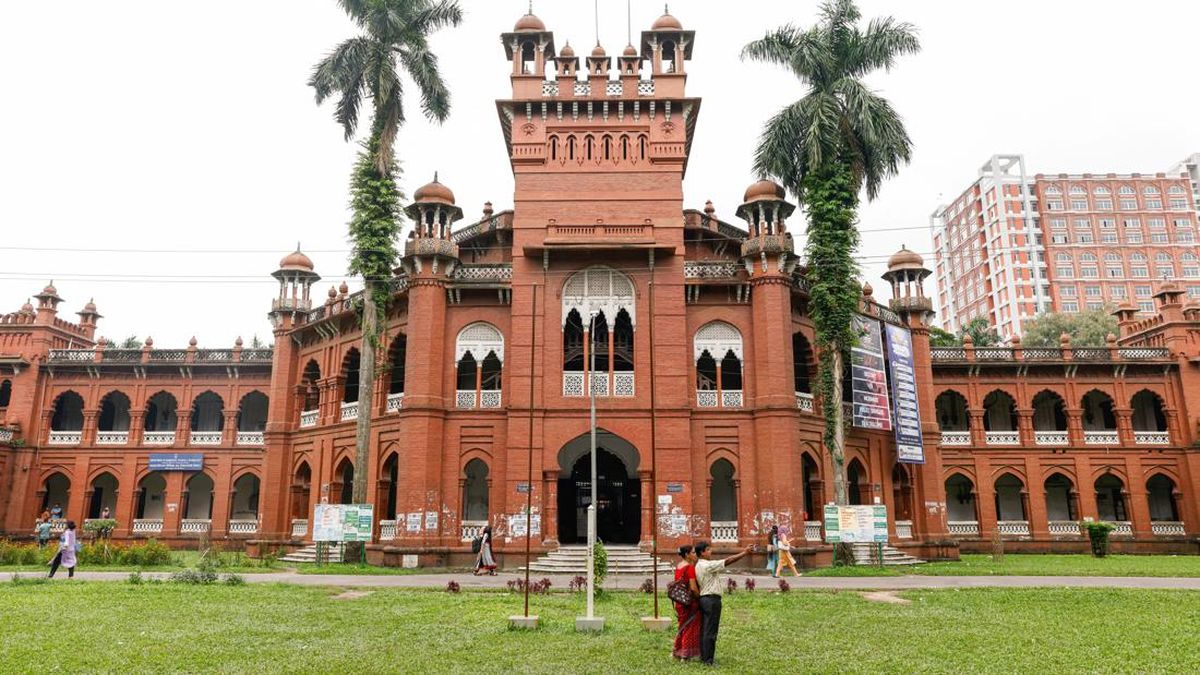

After years away, it can be unnerving to return to the place you call home and feel like you don’t belong.Credit: Getty Images

I felt pushed and pulled in opposite directions, both overwhelmed and underwhelmed simultaneously. Grieving for the person I’d become overseas – liberated, increasingly streetwise, borderline bilingual – I began questioning what version of him could exist happily here.

Then, to my relief, I learnt this phenomenon has a name: reverse culture shock.

We miss being stretched

Clinical psychologist and founder of The Travel Psychologist Dr Charlotte Russell says she sees this with her clients.

“It happens when we’re no longer immersed in a culture we’ve adjusted to,” she says. “We might assume this feels easy, but actually, if we were being stretched in a way that felt meaningful, helped us to learn and build confidence, this may not feel positive.

“We may feel a sense of loss or frustration that we no longer have access to the situations that stretch us and that we find exciting.”

It can, she says, lead to some finding their home culture and routine dull. This can lead to “restlessness, feeling misunderstood, struggling to reintegrate, and longing for aspects of the culture they experienced”.

Loading

‘Everyone seemed brainwashed’

Kieran Ewald, 35, returned to Sydney 2018, having spent four years in Dubai. It was a bumpy landing.

“I’d grown so much by adjusting to Middle Eastern life, then had to shrink myself to fit back in again,” he says. “Everyone here seemed brainwashed, in this closed-minded zombie-like state: enslaved by their routines, cliquey in their cliques and idolising property ownership.”

He says this led to him feeling out of place in his own country.

“There was little space for anyone, like me, who stuck out and was different. I felt like I was a little too loud and too confident and being back in this tall poppy syndrome culture made me feel I was being over the top and should tone it down.”

Ewald puts this “closed off” mindset down in part to Australia’s remoteness. “A majority of people I knew here hadn’t lived overseas,” he says.

It took Ewald two years to re-integrate. During that time, he pined for Dubai.

“I addictively scrolled through photos and videos to trigger memories,” he says. “Any time I wanted to feel more grounded or understood, I’d spend a lot of time calling friends back there; they were also ‘wanderlust’ types.”

Loading

Russell says this is a common symptom of reverse culture shock. “Most research focuses on university students returning from cultural exchange programs,” she says. “Their experiences show that seeking the support of others in similar situations is very valuable.”

She says Ewald was doing the right thing by reaching out to other “nomads”.

“Many recognise they’re not the same person as before their trip and want to reflect on the lessons they’ve learned,” she says. “Journaling and creative ways to mark your experience can also help.”

For Ewald, the same thought kept re-emerging. “I always came back to: I just don’t fit into any group of friends here,” he says. “I kept changing my social circle, in search of people that understand me.”

Life at a standstill

Zara Lim, 30, returned to Melbourne this year after an 18-month overseas trip to Europe and Asia.

Coming home, she says, initially felt fine, with lots of friend catch-ups. Afterwards, the pace of life suddenly felt dramatically slower.

Zara Lim felt like her life wasn’t progressing when she first returned to Australia after 18 months of travel.Credit: Chris Hopkins

“Sometimes it seemed like nothing had changed while I’d been away or like I’d never even left, which is oddly disorienting after constant movement and stimulation overseas,” she says.

When Melbourne’s winter hit, she felt a bout of seasonal affective depression. “At times I’d feel like my life wasn’t progressing, that I was at a standstill and needed other challenges,” she says.

Russell says setting a goal or starting a project is a good idea after returning from a long trip. “It helps anchor you if you’re feeling disoriented or deflated,” she says.

For Lim, establishing new routines worked. “You discard routine when constantly travelling,” she says. For her, a running routine – and an ambitious new goal – helped her settle. She signed up for, then completed, a marathon.

Yet still, it took about five months to feel even slightly anchored. “I’m not sure I’ve ever felt fully settled since returning home,” she says. ” I often get that pull to go overseas long-term again.”

This is despite Melbourne being regularly named one of the world’s most liveable cities. “Liveable doesn’t always mean exciting,” Lim says.

Russell cautions against generalisations, such as the culture being parochial.

“Reverse culture shock isn’t about the culture itself being ‘stifling’ or inadequate, but the stark contrast after adapting to a different rhythm,” she says. During the readjustment period, she advises against rash decisions. “Allow time to re-adjust – at least six months.”

‘I came back a different person’

Liam Miller, 41, returned to Sydney in December 2018 after living and working as an e-commerce specialist in London and then Barcelona for four years.

“After that initial excitement wanes, and you’re caught up with everyone, reality sets in,” Miller says. “You’re starting from scratch socially. I came back a different person and felt like I didn’t belong – many friends were now in relationships and had quit late nights out.”

He says they weren’t purposely excluding him. “You’re just no longer front of mind.”

This led him to question whether he’d made the right decision to return.

Liam Miller found living back in Australia challenging after extended time in Barcelona and London.Credit: Dylan Coker

“In Spain the culture is very much ‘work to live’. People seemed less stressed and more keen to have fun,” he says. “Here, it’s more ‘live to work’ – and buy a property.”

He remembers saying aloud to himself, “This’ll take time.” It ended up taking two years.

“You can’t just jump on a plane somewhere for the weekend here when you get bored of the same culture,” he says.

The project he threw himself into was founding Kiki Clubhouse – a social club which connects LGBTQI people who, like him, may feel left behind when they return from travels to their friends having moved away or moved on to a different stage in life.

“Whether they’ve just arrived in Sydney or been here for 20 years, it’s a place for those who find themselves needing to make new friends,” he says.

You grow when you stop and rest

Readjusting to life back home is about navigating “the gap between the identity you’ve developed overseas and the one you left behind”, Russell says.

I’d run on cortisol, adrenaline and dopamine while I was away. Every day I stepped foot outside, I was in a constantly challenging and stimulating environment as a foreigner. Back home, I wasn’t exotic.

Loading

I did, however, resist the invitation to call Australia comparatively boring. It isn’t. But it also isn’t helpful framing.

Russell says: “Try not to judge differences between cultures as better or worse. It’s much more helpful psychologically to take an observer stance and recognise that all differences come with positive and challenging aspects.”

This was always going to be the most important part of my travel: when I stopped. When there’s pain, when you recalibrate – that’s when you grow. And rediscover how the new version of yourself fits into your old life.

‘I never rediscovered my groove’

For Ewald, however, seven years after returning, it may be time to call it.

“I’d hoped to find my groove and community here, but I still struggle,” he says. “I’m currently asking myself if Australia is really where I want to be.”

This has led to a big life decision. “Maybe in 20 years when I’m looking to settle down, I’ll return to Australia. We have a beautiful country, with so much to offer. But I feel like I’ve really done it, over and over. I’m ready for a change. I have my eyes on Bali.”

Make the most of your health, relationships, fitness and nutrition with our Live Well newsletter. Get it in your inbox every Monday.

Most Viewed in Lifestyle

Loading