How is that an Aussie fair go, for the War Memorial to change the rules at half-time?

Opinion

September 14, 2025 — 9.50am

September 14, 2025 — 9.50am

I was surprised. I was not surprised.

Surprised at the news my book Flawed Hero had been twice rejected by the Australian War Memorial as the winner of the Les Carlyon Literary Award despite being so nominated by independent judges – because I did not know it had been entered; the entry facilitated by Allen and Unwin rather than myself.

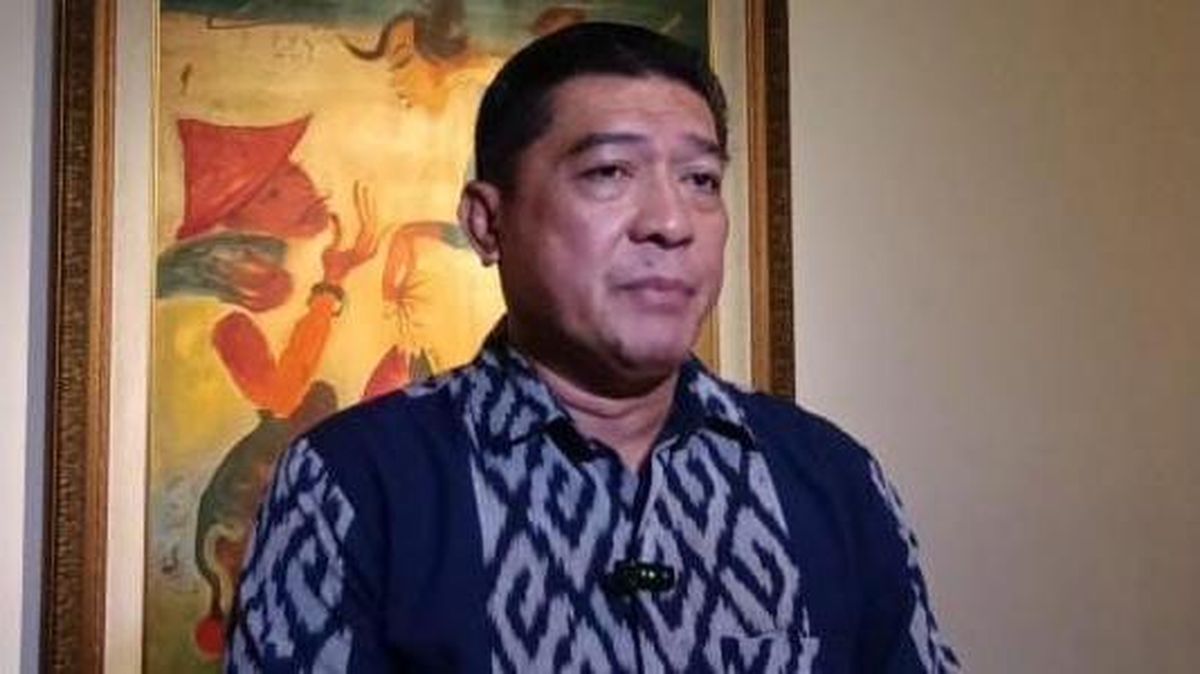

Chris Masters speaking outside court after Ben Roberts-Smith lost his defamation case against The Age, The Sydney Morning Herald and the Canberra Times.Credit: James Brickwood

But once that news was processed, I was not surprised. While Flawed Hero has gained credit in some spheres (it was awarded the 2024 Australian Political Book of the Year prize), within other quarters of the Australian War Memorial it appears to be reviled.

Let me go back to 2017 when I sat down with the then director, Brendan Nelson, trying to nervously broach the subject of Ben Roberts-Smith, VC, MG, and why the memorial should be cautious about making him a centrepiece exhibit.

Loading

Having helped curate the Afghanistan galleries, I got on well with Nelson, but this was a delicate subject given Ben Roberts-Smith’s mentor and employer, Seven network boss Kerry Stokes, was the memorial’s chairman.

For me, the relationship with an institution I long admired went downhill from there. Nelson became Roberts-Smith’s most influential and outspoken advocate as the scandal broke that Australia’s most decorated living soldier might also be a war criminal.

Stokes became an even more forceful champion of his poster boy, an army corporal promoted to general manager of the Seven network in Queensland.

After a torturous seven years and three courtroom adjudications, the difficult reporting by this masthead’s Nick McKenzie and myself for the rival Nine network was found justified, with Stokes left little change from an estimated $30 million-plus in costs.

The cover of Chris Masters’ book on the case against Ben Roberts-Smith.

As the strength of evidence against Roberts-Smith became apparent, Stokes was unswayed. In November 2022, he told a reporter: “Ben Roberts-Smith is innocent and deserves legal representation … scumbag journalists should be held to account.”

Given its advocacy of Roberts-Smith and treatment of my book, I could be forgiven for thinking the media magnate’s messenger blaming is shared by some at the memorial.

Which takes us to the bigger picture of truth-telling about the experience of war and Australian remembrance culture. At that 2017 meeting with Nelson, I remember telling the talented orator how he had found great words two years earlier in commemorating the Anzac Centenary, and that maybe he could find some more. At this stage, the Brereton inquiry into alleged war crimes in Afghanistan was under way, with a strong sense emerging that Australia was about to stomach some hard news. I thought the War Memorial could get in front, acknowledging an unremarkable reality that war brings out the worst as well as the best in us.

When the memorial was opened on Armistice Day in 1941, then governor-general Lord Gowrie spoke of its purpose. It would act “not only as a record of the heroic deeds of those who fought and fell in the last war but would also be a reminder for future generations of the brutality and utter futility of modern war”.

Loading

Charles Bean, the author of The Anzac Book and founder of the memorial, was one from my reptilian ranks – a journalist. Just as I can be starry-eyed about the Australian soldier, so was Bean. Even so, Bean did not run from the truth about the ugliness of war.

He reported angry Australian soldiers having suffered losses bayoneting Germans who had surrendered. He wrote: “The Germans in this case were entirely innocent, but such incidents are inevitable in the heat of battle, and any blame for them lies with those who make wars, not those who fight them.”

Now 110 years on from Anzac, Australia may be ready for a rounded account of the experience of war. It is not difficult. We can take it. By all means honour the bravery and sacrifice, but let’s not ignore the blemishes.

And for what it is worth, the Roberts-Smith transgressions as investigated by me, Nick McKenzie and the Brereton inquiry are not excused by the heat of battle. The courts ruled on the balance of probabilities that Roberts-Smith committed, or was complicit in, the murders of four Afghan men who were under the control of Australian forces.

Australian soldiers I worked alongside in Afghanistan showed courageous restraint in a morally exhausting environment. They risked their lives, acutely aware of the difficulty telling the difference between innocent farmer and insurgent combatant. They knew well that killing the innocent was not only morally wrong but increased risks to themselves. I believe the vast majority condemn the murder of defenceless prisoners.

And a final word about the book prize, denied when the criteria were adjusted to eliminate established authors like me. How is that an Aussie fair go, to change the rules at half-time?

Chris Masters is a Gold Walkley award-winning journalist and author. He was the first Australian journalist to be embedded with special forces in Afghanistan.

Get a weekly wrap of views that will challenge, champion and inform your own. Sign up for our Opinion newsletter.

Most Viewed in National

Loading