We stepped onto the balcony, beach-bound with towels slung from shoulders, when the black column of smoke in the sky stopped us dead. “Grab your camera,” I told my fiancé, and we jumped in the car and drove from his mum’s home towards the plume looming over the Central Coast, north of Sydney.

We pulled up outside Woy Woy railway station. Wild flames flared about 30 metres from homes on the other side of a narrow channel of water. By the time a Watch and Act alert had pinged on my phone, battling for reception in the smoke, the flames vaulting off the tops of gum trees had reached the size of buildings.

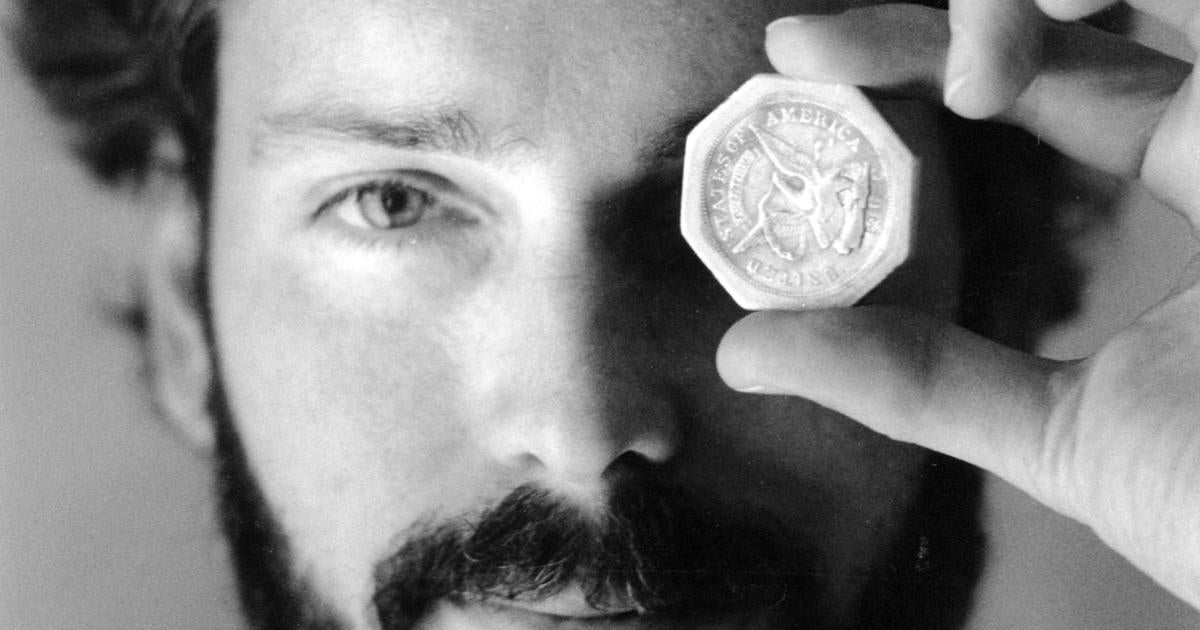

The scene when we arrived at December’s fire near Woy Woy on the Central Coast.Credit: Alex Beauman

Unbeknown to us, homes were burning on the other side of the bushy hill in Koolewong. Locals began to gather nearby. One had just made it out; she’d taken a video on her phone of a plane thundering low over her street dumping jets of pink fire retardant. To the left, her neighbour’s backyard was on fire.

Until she heard the plane’s roar, she’d been obliviously unpacking the groceries.

Sixteen homes were lost in the fire that flared last month. Watching how fast flames blazed from smouldering patches into house-threatening columns showed that even the most prepared and well-resourced authorities are still trying to outpace a danger as fast and unstoppable as the wind that drives it. Early warning, and survival, will never be guaranteed.

There are always those that eye-roll at the intense media coverage during heatwaves. Scorching days are just part of Australian life, they say. It’s true that even the tinge of burning eucalyptus oil on the air is a perversely nostalgic scent of summers past.

Sixteen homes were destroyed by a bushfire in Koolewong on the Central Coast.Credit: Sitthixay Ditthavong

But the reality is heat and fire are behaving in a way that is no longer natural. An atmosphere driven hotter by the burning of fossil fuels is worsening heatwaves and mutating fire behaviour. And that’s killing people. Of 178,486 deaths related to a global heatwave in 2023, more than half were attributable to human-induced climate change, one analysis found.

When Saturday’s temperature spikes at 42 degrees in Sydney – 16 degrees above average – the heat on your skin, the sweat on your brow and the possible scent of fire will be intangibly but meaningfully linked to every tonne of carbon dioxide and methane unleashed into the atmosphere.

Climate change also “supercharged” the 160km/h winds and record dryness that unleashed deadly winter fires in Los Angeles almost exactly a year ago, the Climate Council reported this week. Those fires, bizarrely, struck in winter. And this weekend’s fire conditions are also abnormal, said Monash University climate expert Adjunct Professor Andrew Watkins.

“What’s unusual is having such extreme heat and fire conditions during a La Niña summer, and following a strong negative Indian Ocean Dipole,” he said of the two rain-summoning systems. “Normally, we would be more worried about floods with those climate drivers.”

A satellite image of the LA fires.Credit: Maxar Technologies

Further, cycles of rain followed by sapping heatwaves – which rapidly dehydrate fine twigs and leaves into tonnes of forest kindling – amp up fire risk in a new regime dubbed “hydroclimate whiplash”.

How can we underscore just how dangerous and strange this weather is; how do we emphasise that summer heat is no longer innocent, but transformed by carbon emissions into an increasingly deadly threat?

We might look for inspiration to the fierce weather system bearing down on Queensland, a swirling storm likely to intensify into a cyclone. (Yes, there are flash floods expected in the north as the south of the country burns).

Cyclones are given names mostly to help raise public awareness of their impending dangers. Why don’t we do the same with severe heatwaves – by far the deadliest kind of extreme weather event?

“Names can make hazards more memorable,” wrote Professor Steve Turton and Samuel Cornell, the researchers who proposed the idea this week in The Conversation. “Research shows naming weather events helps people recall warnings, share information and prepare more effectively.”

A study into the world’s first named heatwave – Spain’s heatwave Zoe in 2022 – found people who remembered the weather event’s name were more likely to stay indoors, check on others and follow their local government’s advice.

Loading

Borrowing from the official list of approved cyclone names, we could have a heatwave named Hayley, Peta or Iggy.

It’s hard to think the 2019-20 bushfire season would have had the same lasting impact on Australian consciousness, and acted as a lightning rod for climate awareness, if it hadn’t been branded Black Summer.

Severe heatwaves like the one swamping us this weekend are becoming more common. But that doesn’t make them normal.

Marking the moment with names, as we do for other crises, could help remind us of that.

The Examine newsletter explains and analyses science with a rigorous focus on the evidence. Sign up to get it each week.

Most Viewed in National

Loading