Costa Mesa, California: “You want China to know that these types of things exist,” says Palmer Luckey, the sandal-wearing tech entrepreneur who co-founded a cutting-edge weapons company.

His defence tech firm, Anduril Industries, makes the autonomous underwater Ghost Shark vehicle, a weapon designed and built in Australia relying on local supply chains.

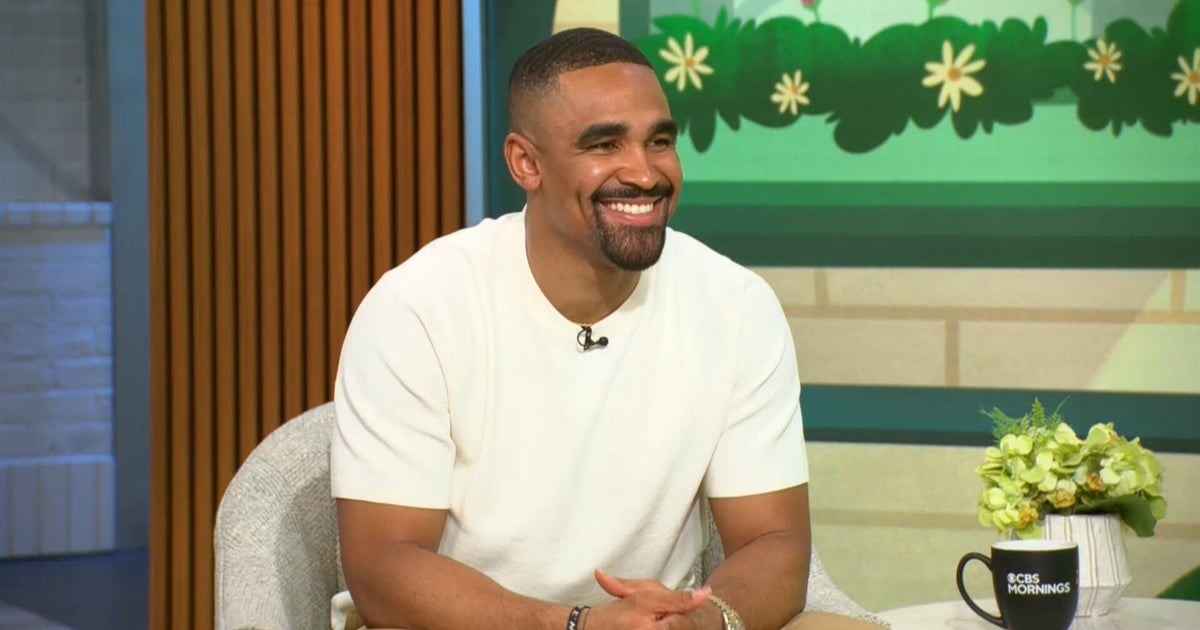

For defence, local production capabilities are everything, says Anduril Industries founder Palmer Luckey.Credit: Bloomberg

Luckey’s talking about cruise missiles, saying how in a conflict with China, Taiwan needs to be able to continue to build cruise missiles so it can fight an occupation.

A similar sovereign capability underscores the Ghost Shark. Should Australia’s sea lanes be cut off in a crisis, localised production gives it the chance to fight back.

Luckey comes across as pure Californian. In his trademark Hawaiian shirt, shorts and thongs, he evokes a strong beach vibe, with a boyish enthusiasm for his main jam: software-led defence technology. He, like many of the minds at Anduril, sees a world of security problems that can be addressed, if not solved, with innovative engineering solutions.

We – a bunch of journalists – are visiting Anduril’s Southern California headquarters. Its foyer doubles as a showroom of drones – aerial, naval and uncrewed mini-subs. We’re heading for a conference room with a huge video screen and the chance to get a front-row glimpse of a company building the toolkit of future warfare.

Anduril Industries’ headquarters in Costa Mesa, California. Credit: Chris Zappone

When we reach the room, Luckey speaks across a massive wooden conference table we’re gathered around: telling us how localised weapons production will be key to winning a future war.

By way of analogy for Taiwan, he asks us to imagine what the US occupation of Afghanistan would have looked like “if Afghanistan was a global tech powerhouse filled with top engineers?”

Luckey at the company headquarters.Credit: Chris Zappone

“It would have been a very, very different occupation,” he said. The US and allies, like Australia, would not have been able to hold territory as it did in the 20-year conflict.

Anduril’s conference room would not be out of a place in a Bond film – apart from having more natural wood tones and less aluminium.

As an aside, Luckey explains the glories of turbine-powered drag axles on 1960s hotrods, made by a California company years ago. He owns a Torbinque turbocharger himself.

Car culture, famous in Southern California, is evident at Anduril. In October, the company announced it would sponsor NASCAR racer William Byron.

Perhaps it’s because of the love of machines, engineering, and building tangible things that Anduril’s headquarters doesn’t feel like a coder-dominated tech company.

The Costa Mesa facility occupies the former Los Angeles Times printing press building. It has a fabrication area where engineers, technicians, welders and machine operators make small batches of newly designed, high-tech weapons.

The ability to sustain weapons production at scale is crucial to staying in a fight, Luckey tells us.

Anduril Australia plans to build “dozens and dozens” of the Ghost Sharks, at a cost of $1.7 billion, which are expected to have a range that is “significant for the Pacific”.

But simply possessing Ghost Sharks, or Anduril’s Fury autonomous warfighters, or its Barracuda cruise missiles is not enough to win a war.

Loading

In the information era, your adversaries must be aware of what you have, and your capacity to mass produce the weapons, so they can shape their risk calculus.

Anduril produces compelling animation and sizzle reels of AI-driven autonomous weaponry to highlight their potential to the world.

This has led critics to question the ideology of the emerging defence sector. Along with other US tech luminaries such as Palantir’s Peter Thiel and Alex Karp, Luckey supports Donald Trump. His and other tech barons’ stance gives them deep access to Washington at a time of growing geopolitical tension.

Professor Elke Schwarz, of the Queen Mary University of London, has described how defence tech companies promote “a fantasy of omniscience and omnipotence” that, while “terribly alluring … does not bear out against the history of warfare or the character of war as a human affair which abounds with subterfuge, surprise and subversion”.

Other detractors include University of Antwerp political science researcher Dr Robin Vanderborght and Dr Anna Nadibaidze, of the University of Southern Denmark Centre for War Studies, who wrote of Luckey: “Not only through his words, but also through his whole performance – acting in front of the audience as an eccentric, no-nonsense arms dealer – Luckey aims to radiate prophetic credibility and untapped knowledge over the future of warfare.”

The cutting-edge, rapidly prototyped technology of companies such as Anduril is developed in the name of “rebooting the arsenal of democracy”, Vanderborght and Nadibaidze said. “[But] these companies’ strategies risk severely weakening the very democratic project these companies are so adamant to defend, especially in the US context.”

Loading

A spokesperson for Anduril said while there would still be things in warfare that were unpredictable, the conflict in Ukraine, for example, gave “strong evidence of the way in which modern conflicts are playing out.”

Critics also point to the cosy relationship between Silicon Valley’s defence sector and the increasingly autocratic Trump administration. Anduril says it is on the record as being a “bipartisan company” that works with the major parties in the US and Australia alike.

Militarily, Luckey sees weakness and risk. He believes the US and allies would be on the back foot in a future conflict. China is “building a fundamentally offensive military force oriented around launching and sustaining an invasion and occupation,” he said.

And Western democracies are “for once, kind of on the flip side …” of weapons developments, getting away from offensive weapons.

Instead, they are trying to build something that would create doubt in enemies’ minds about whether they can succeed in attacking us, a reference to the Porcupine strategy, also known as the Echidna strategy.

Luckey notes: “all of our allies” are asking for the same capabilities: military vehicles that can, more than dominate an adversary, sow doubts among adversaries in their ability to successfully attack democracies.

For a protracted war, of the kind Luckey could foresee between Taiwan and China, the population having the will to fight would be essential, too. That would be true for any democracy, including Australia and the US.

The messages from Anduril to its employees about their mission are revealing.

Loading

Palmer Luckey, who wrote for his California university’s news outlet, publishes a printed company newsletter, Palmer Press. After a dig at Anduril by a defence-tech competitor, Luckey, in full founder mode, counselled staff: “We should absorb their negative energy and use it to push ourselves even harder.”

On the walls at the company HQ are the names of inventors and designers such as [Johannes] Gutenberg of movable-type fame, and [Charles and Ray] Eames, who were involved in World War II production innovation.

One wall has a lengthy quote discussing Anduril’s mission. “There is no secret government silo of advanced technology that will save us if war breaks out – you must build it.”

Chris Zappone travelled to the US as a guest of Anduril Industries.

Most Viewed in Business

Loading