The peak body for gyms has blasted a proposed tightening of consumer law that would make it easier for customers to cancel memberships and exit so-called “subscription traps”, arguing it could threaten the sector’s viability.

As gyms prepare for the annual influx of members signing up in line with new year’s resolutions, AUSactive, which represents chains including Anytime Fitness, Snap, Fitness First, Fernwood as well as small operators, is pushing back against the Albanese government’s unfair trading practices framework.

Labor’s proposed reforms are aimed at plugging holes in existing consumer law. Subscription traps have been identified as one of several “dark patterns” employed by businesses that would be deemed unfair and prohibited.

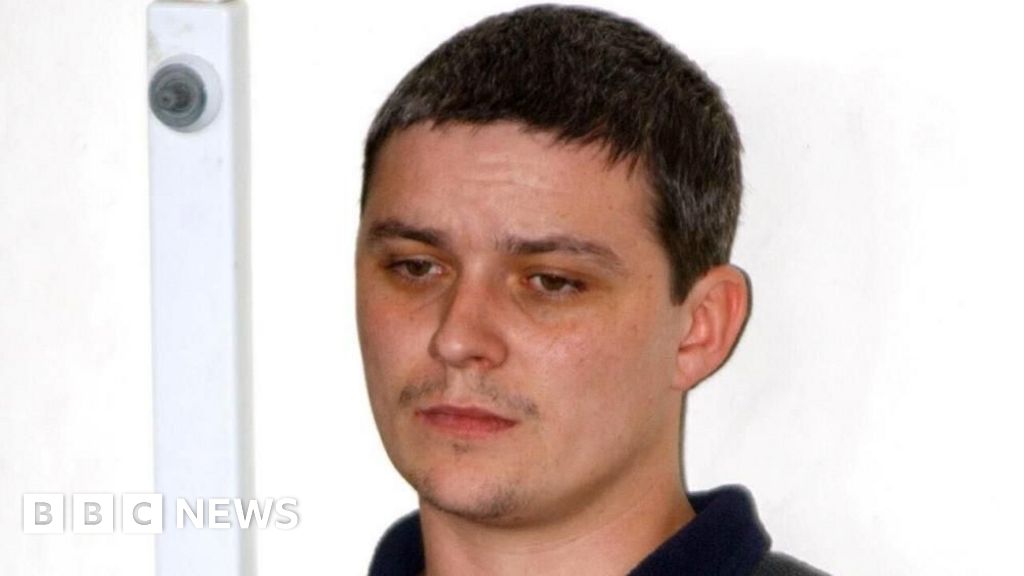

Lynsey McGee, a manager at Hiscoes Gym in Sydney’s Surry Hills.Credit: Flavio Brancaleone

While subscription traps have been largely framed in terms of online platforms, Assistant Competition Minister Andrew Leigh has flagged gyms specifically as being under the scope of the reforms, which were first put on the agenda in the previous term of government but which have gained recent momentum after state and territory consumer affairs ministers agreed in November.

Ahead of a final consultation period before legislation that is expected next year, AUSactive chief executive Ken Griffin said he was concerned that laws written with online platforms in mind would bluntly apply to bricks and mortar gym businesses.

Loading

“Scaled online business models such as Netflix are fundamentally different to owning a gym, which means a physical place which requires the owners to pay rent and pay for staff, supervision and other running costs,” Griffin told this masthead.

Existing laws broadly protect consumers against unfair contract terms, but critics such as the Consumer Policy Research Centre have said it is common for gyms to not specify exact rules for cancelling in the wording of membership contracts, such as exit procedures and other penalties.

Gyms often require proof of moving residence to an area without one of the brand’s branches, or a medical certificate proving an inability to exercise in order for members to exit lock-in memberships. Longer-term memberships are often discounted accordingly, but if cancelled early, they can require paying out the value of the remaining contract.

Proponents of the reforms also cite other traps for gymgoers, including that gyms require members to phsyically come into a branch for a specific time to discuss their exit with staff; as well as unreasonably harsh fees or limits on pausing memberships and exit fees above the value of the remaining contract.

Consumer advocates have asked the government to craft the legislation to make it “as easy to cancel as it is to sign up”, wording which closely resembled the phrasing of a Biden-administration push for similar laws. However, these were ultimately struck down by a US federal appeals court in July, days before coming into effect, due to procedural deficiencies.

Griffin takes particular issue with this phrasing. “At the point someone wants to cancel a gym membership, it would be ridiculous if they had to do what they did to join, to require them to come in and do a consultation with a trainer, to go through a test of which equipment is safe, just to cancel. So that principle ... would be silly in our case,” he said.

Griffin said laws that would make it easier for people to exit contracts could go against the industry’s traditional business model, which incentivises revenue certainty from members by offering discounts.

Lynsey McGee: “Having ongoing memberships, and making members want to renew is really important.”Credit: Flavio Brancaleone

“If someone gets a deal, say for 12 months at a discounted rate, they gave that certainty to the owner of a gym, and the owner can bank on that income, so they can have the certainty to employ a requisite number of staff,” he said.

“Members have an expectation they can come into the gym at any time they want, use the equipment they want or get into a class they want. Gyms have to be ready for that.”

He said gyms were obligated to “hold up their side of the contract” even if a member didn’t show up frequently. “I think that’s one of the things that might be forgotten here: You may not have turned up for your spin class or gone in to use the elliptical, but the gym still had to make the preparations as if you did,” he said.

Lynsey McGee and Mac Redinbaugh, who run the independent Hiscoes gym in Sydney’s Surry Hills, say smaller operators have to be more accountable to their members.

Redinbaugh said: “This is a community gym. I eat my breakfast out the front. If I was making any part of this process unpleasant, I’d have to eat breakfast next to these people whose lives I’ve made harder. If somebody doesn’t like something, they can come up and yell at me.”

The pair say they have leant towards offering more short-term memberships and making it easier for people to cancel longer-term ones because they have seen ex-members return after an easy process.

McGee said: “Membership is basically our sole income. We might sell a couple of squash balls or Gatorade, but membership is far and away how we make money and run the businesses. So having ongoing memberships, and making members want to renew is really important.”

Ultimately, McGee believes laws that would ban businesses from trapping customers by making it overly hard for them to cancel are welcome, but she wants careful consideration so that online-centric provisions don’t harshly apply to gyms and owners of small businesses with physical premises.

Redinbaugh said: “We don’t have legal departments. We’re not one of those predatory companies with big resources to find a way around laws like this.”

AUSactive has a voluntary code of conduct, which has a limit on maximum membership length and cooling-off periods. Griffin believes the code is more sensible to improve the sector.

Memberships are the main income stream for the nation’s roughly 8000 gyms and fitness centres, accounting for about $2.2 billion of the sector’s $3.7 billion annual revenue, according to IBISWorld analysis from this month. Personal training brought in about $472 million in revenue: classes generated $417 million, and casual entry fees totalled $304 million.

Loading

CPRC CEO Erin Turner said that while some gyms had developed good practices, much of the sector “needs to clean up their act”.

“Gyms definitely have a lot to answer for. I think they’re the originators of subscription traps, something which has gotten worse in the online world,” she said.

Turner said cumbersome or costly requirements to end memberships made it harder for customers to shop around and accept better offers.

“If the only reason you’re making money from a customer is because they’re trapped in, then that’s what this law is trying to stop,” she said.

Turner said plugging gaps in the consumer law was important. In addition to unfair contract term law loopholes, she said high pressure sales tactics from gyms were a notorious problem.

Laws already strictly limit unsolicited sales tactics such as cold calling, but if someone has registered for a gym’s free trial, it constitutes an existing relationship, meaning the gym can repeatedly call them pressuring them to take out a membership, Turner said.

The Business Briefing newsletter delivers major stories, exclusive coverage and expert opinion. Sign up to get it every weekday morning.

Most Viewed in Business

Loading