The pattern repeated during the Korean War, when equity markets once again focused on fundamentals rather than battlefield headlines, with the Dow returning around 100 per cent during the early 1950s.

The same counter-intuitive behaviour appeared during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 at the height of the Cold War. Markets initially fell sharply that October but recovered just as quickly, finishing the year higher than where they began. The fear was existential, but the reaction fleeting.

Even September 11, followed by the invasion of Afghanistan, failed to derail markets despite an initial knee-jerk response. In the decade after 9/11 – a period that also contained the tech-wreck hangover and the full force of the Global Financial Crisis - which saw equities fall more than 50 per cent between 2007 and 2009, the Dow still finished the decade higher than where it began. The journey was brutal, but the recovery was just as remarkable.

Commodity markets tell a similar story. Oil prices spiked sharply ahead of the outbreak of both Gulf wars in Iraq before retreating to pre-war levels even as both conflicts continued to rage. Once confidence in supply was assured, the impact of both wars on prices was transient. It’s only when tankers stop or pipelines shut down that the impact on markets can be lasting.

The oil price shocks of the 1970s provide a textbook example of the same point working in reverse. Following the Yom Kippur War in 1973 and the Iranian Revolution in 1979, oil prices surged but, in this case, remained elevated due to ongoing supply concerns. Inflation became entrenched and central banks were forced into aggressive monetary tightening.

The mistake most investors make with geopolitics is assuming markets react to events and headlines. While they may do that briefly, they generally return to norm quickly – that is, unless that event has created a long-lasting consequence – such as a supply and demand mismatch.

By way of another example, inflation and interest rates are another case in point. Geopolitical tensions only become a market problem when they push up costs enough to alter the global path of inflation.

Government spending also plays its part. Wars are expensive, but they’re also stimulatory. Defence budgets swell, infrastructure spending follows and entire industries find themselves pulled into long-term procurement cycles. Markets quite like this. More often than not, they quietly reprice it.

And finally, there are capital flows – the least visible yet most powerful force of all. Money doesn’t flee risk at the first sign of trouble.

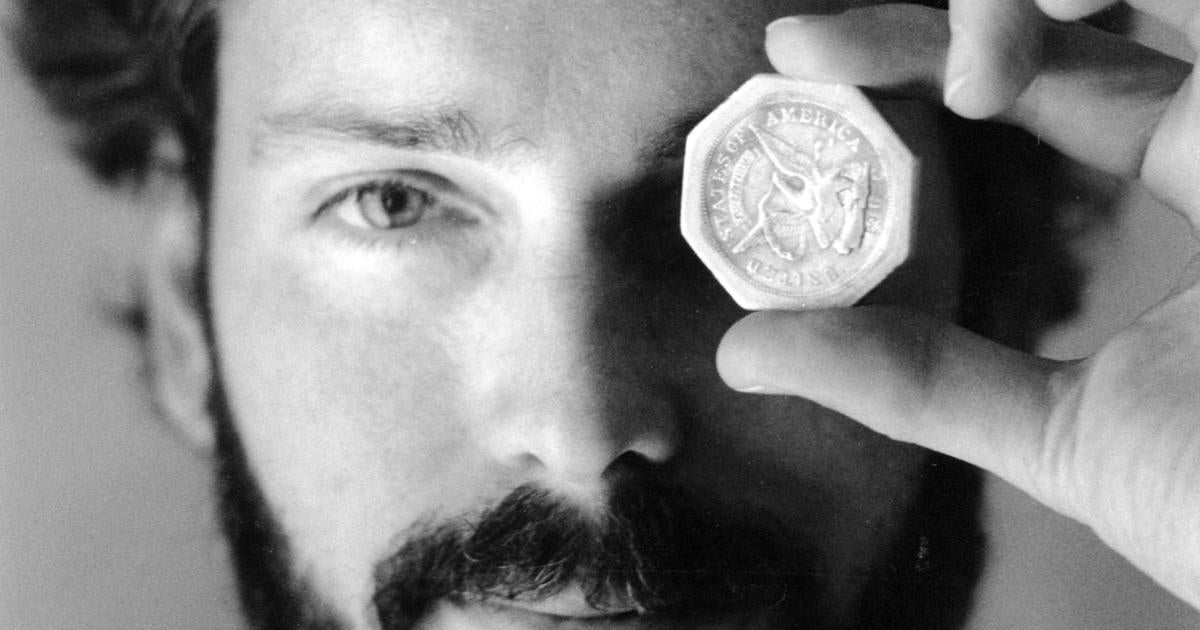

Dollar Bill has seen markets rally through wars, wobble on rumours and fall apart over what looked like minor policy missteps at the time. The difference has never been the headline. It’s always been the follow-through consequences and where there are no obvious long-term consequences, Dollar Bill likes to have a dabble and buy the geopolitical dip.

This also explains why the idea of a universal geopolitical “safe haven” is so often misunderstood. When uncertainty rises, investors instinctively reach for gold, defensive stocks, the US dollar or government bonds as though markets operate on a standard-issue evacuation plan.

They don’t.

Gold has a long and mostly deserved reputation as a hedge against disorder. But it doesn’t respond reliably to conflict alone. Last year’s 70 per cent surge in the gold price was not a simple “war trade”. The fact that gold prices were flat through 2022 – the year war erupted in Europe - confirms the point. Rather, the gold price rally in 2025 was driven largely by central bank buying, which added more than a thousand tonnes to official reserves.

Large fiscal deficits and shifting trade rules remain concerns. But while geopolitical uncertainty may have struck a match, the fuel behind recent moves in gold – alongside silver and even copper – has been driven mostly by physical demand.

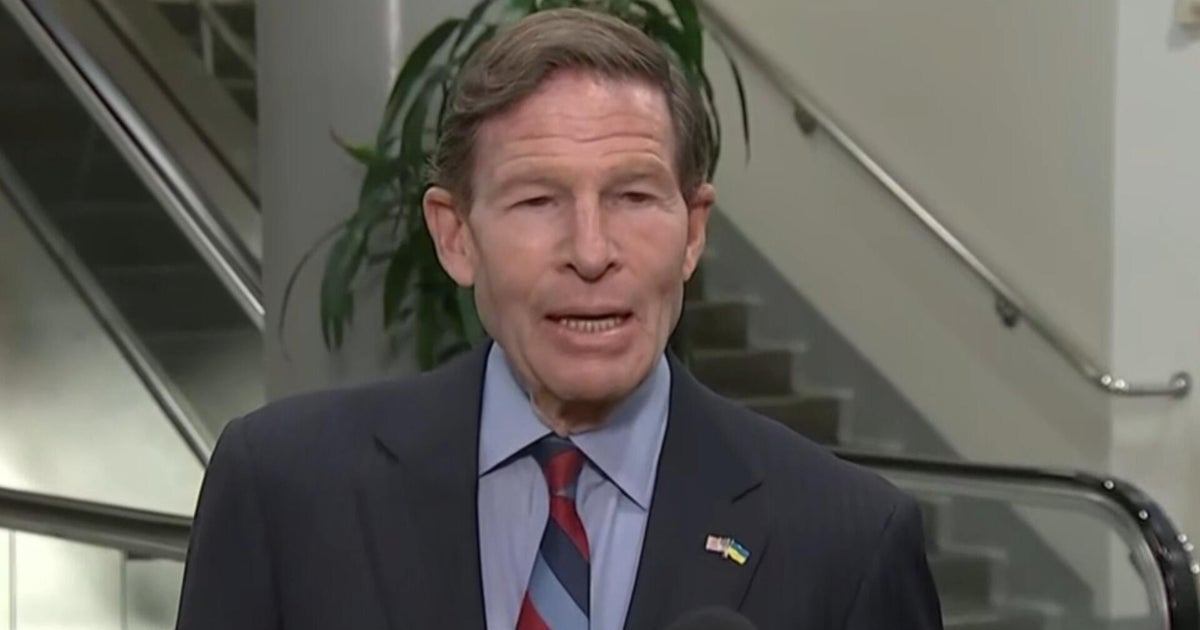

The same logic applies to politics. Loud, erratic leadership can dominate headlines without derailing markets. Since Donald Trump’s return to the White House last year, US equities have continued to move higher, adding more than 15 per cent despite a steady stream of headlines that have so far amounted to little more than noise. Markets remain far more interested in liquidity, earnings and interest-rate expectations than theatre.

Which brings Dollar Bill back to the Club, where the chatter has grown louder as the new year begins. The leather recliners are full, the smoke hangs heavy and every second conversation ends with the same conclusion: this time feels different.

Maybe it does. And maybe it should. But equity markets say, not yet.

What markets are watching aren’t the headlines themselves, but whether tensions bleed into the real economy in lasting ways. Do conflicts drag on long enough to tighten supply? Do energy prices stay elevated rather than spike and fade? Do governments respond with clarity or confusion? Do central banks find themselves forced into choices they’d rather avoid?

These aren’t dramatic questions. They’re decisive ones. Markets don’t turn on moments – they turn on persistence.

For now, equity markets appear to be doing what they’ve always done in uncertain times – balancing the known against the unknowable and deferring judgement until the evidence of real and lasting change hardens.

As Dollar Bill drained the last of his Lafite and raised his hand for a second bottle, another regular leaned over and declared that markets were mad not to be panicking yet. Dollar Bill remains unconvinced.

And as last drinks were called and the Club began its slow surrender to the night, the screens above the bar started to flicker with breaking news that the United States had launched military action in Venezuela, also removing its president in a move dramatic enough to make even the old hands pause mid-pour.

The reaction around the room was immediate and theatrical. Someone muttered “oil shock”, another reached for his phone, and a third declared -with absolute certainty - that markets would be in freefall first thing Monday.

They weren’t.

Dollar Bill has heard this soundtrack before. And if history offers any guide at all – as pointed out above - the most dangerous response in moments like these is the knee-jerk one and mistaking the noise of the event for the weight of its consequences.

In an attempt to sound wise amongst his peers, Dollar Bill occasionally likes to quote that great doyen of investing, Warren Buffett, whose best quote is immortalised on the wall at the Club above the side bar. Buffett said: “Be fearful when others are greedy and be greedy when others are fearful”.

Ah, God love him. Time to sign off, and last drinks be damned - that second Lafite has arrived.

Is your ASX-listed company doing something interesting? Contact: [email protected]