It’s 1985 and Melbourne mum Dorothy Millard is firing up her Commodore 64 to play The Hobbit, one of her favourite computer games. After fighting off trolls and escaping goblins, she documents her journey by drawing up a detailed map and noting down her solutions, ready for when fellow players call her dedicated Hobbit helpline for guidance on how to level up.

This was a normal day in the life of a gamer back in the 1980s and early ’90s, when tangible, analog forms of communication were king. If you got stuck while playing a game, you would have little choice but to call a friend, scour a gaming guide, or head to the local arcade to watch the masters at work.

A screenshot of The Hobbit (1982) courtesy of Beam Software.Credit: ACMI Collection

A lot has changed in the four decades since then. Telephone helplines like Millard’s, who died last year, have faded away, replaced by quick-fix options such as Google and Reddit. Instead of sharing tips and tricks at local computer clubs, today’s gamers simply tune in to virtual servers on the Discord group chat.

“Gaming could be deeply frustrating back then,” says Dr Helen Stuckey, a senior games lecturer at RMIT’s School of Design. “People played The Hobbit for over three months trying to figure out how to solve things … So helplines like Dorothy’s were really important. People just had to share knowledge – there was no other way.”

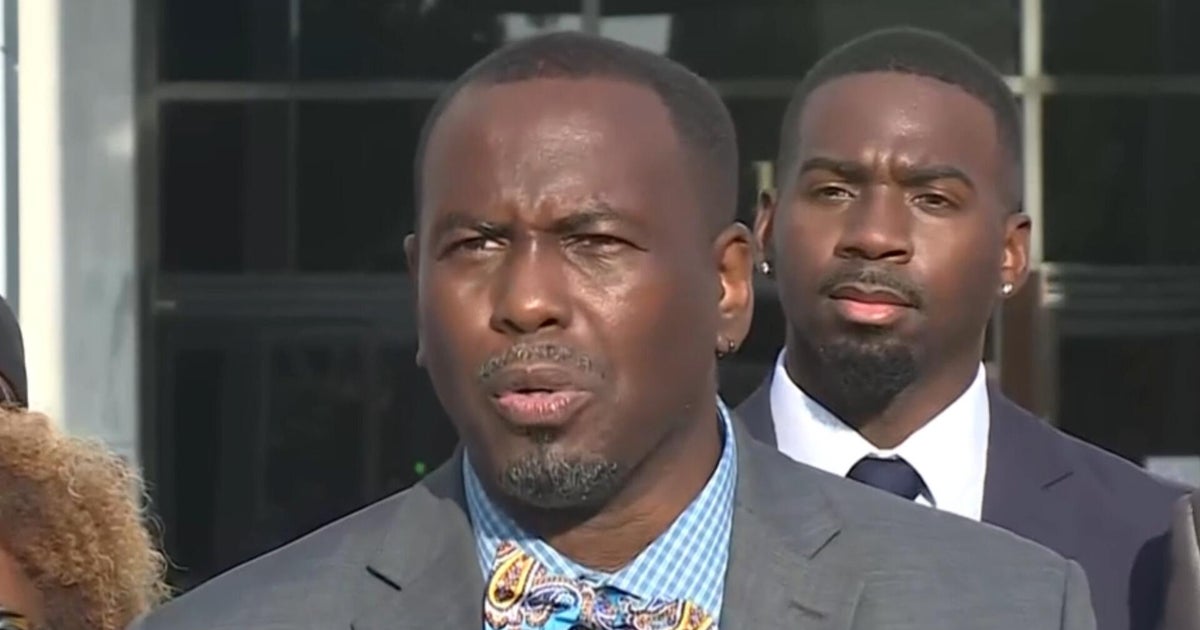

Dr Helen Stuckey says gaming in the 1980s could be both extremely frustrating and fulfilling. Credit: Simon Schluter

Despite how difficult gaming could be, Stuckey says the feeling of finally overcoming an obstacle was beyond fulfilling. It’s this feeling that the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) aims to recreate at Game Worlds, a playable exhibition that features more than 30 iconic video games from the ’70s to now.

While reminiscing about games such as Team Fortress and the early Sims – for which strategic positionings and cheat codes were once whispered among friends – you can’t help but wonder: has it almost become too easy to master games now?

A screenshot of The Sims 4 (2014), courtesy of Electronic Arts.

The early days of game mastery

Telephone helplines and word of mouth weren’t the only ways early gamers gathered tips. Stuckey says gaming magazines, such as Nintendo Power and GamePro, were often lifelines for gamers thanks to their dedicated help columns such as “Pak Watch”, which contained maps, cheat codes and hidden item locations.

“A lot of the computing clubs at the time, like the one Dorothy ran in Nunawading, would meet in person, but also send out newsletters,” she says. “They would have full lists of tips and information about games software.”

Guides were also extremely popular, especially for lengthy role-playing games such as Final Fantasy VII. They were essentially the equivalent of a contemporary FAQ page, only they were hefty, printed guides that included detailed walkthroughs, character statistics and enemy lists.

Final Fantasy XVI Online (2023).Credit: Courtesy of Square Enix.2

Stuckey says that as Web 1.0 took hold, much of the information gathered from zines and clubs transferred onto bulletin board systems (BBS), computer running software that allowed users to connect via a modem and phone line to share information, leave messages and exchange files.

Tim Koch, co-creator of the ACMI-featured microgame Salix8 Sunset, says he remembers using BBS in primary school.

“You would connect your Commodore, Amiga or any early computer by literally using a standard phone line to ring bulletin boards in Melbourne or Sydney,” he says. “I remember Julian Assange was even on the same Commodore 64 bulletin board in Melbourne.”

If you couldn’t find the advice you needed via these forums, Koch says, many young gamers would trawl through gaming magazines at newsstands and “scribble cheat codes on the back of their hands”.

“That opened up a whole other industry in terms of cheat cartridges,” he says. “You’d buy devices that would slow down your machine or freeze the memory. Then you could hack or code in cheats to specific aspects of a game so that the structure changed, and you could more easily finish it … You could interact with the game mechanics a lot more, and break what shouldn’t be broken.”

Video game case study: Neopets

Zac Silverman, a New York-based Neopets ambassador who is better known by his Neopets name “Macosten”, says the virtual pet game was inundated with niche forums and fan-made websites in the late ’90s and early 2000s. If you wanted to share tips on how to best train your Neopet for the “Battledome”, for instance, you would have to program your own fan site.

“You can consider that your Web 1.0 proto-social media,” he says. “The forums weren’t all-encompassing in that they didn’t cover all topics. So you still had to go to different websites to discuss different things.”

Then there were the Neopets guilds, which were basically social clubs. Silverman says these are still around today, but have largely shifted to online mediums such as Facebook groups. Additionally, there is Jellyneo, a virtual guide for all things Neopets.

Each of these resources have evolved alongside the internet, Silverman says. Where guilds would have once met in-person, they eventually shifted to Skype or AIM Messenger. Now, they are largely on Discord. As for Jellyneo, Silverman says social media more or less completely killed the online guide’s forums, though the remainder of its resources are still used today.

When Neopets launched in the late ’90s, players shared tips and opinions via guilds and fan-made websites.

Is it too easy to master games now?

These days, a single search in Google or ChatGPT immediately delivers comprehensive guides, full YouTube walkthroughs, and Discord servers for real-time discussion. The shared, hard-won discoveries of the ’80s and ’90s have been replaced by the convenience of instant (and endless) information.

This has eliminated some of the mystique around gaming, Koch says. “It feels more closed-circuit in terms of how we interact with games. It’s perhaps more homogenised and compartmentalised.”

Now, Koch says, gamers appear to approach games with more focus than creativity. While modern players don’t need to understand a game’s coding, gamers in the ’80s and ’90s often learnt basic programming so they could bypass certain challenges. This generally enhanced knowledge of the mechanics and encouraged experimentation.

Playing games on the original Commodore 64, replete with floppy disk drive and datasette, was nothing like playing a game on the powerful machines of today.

Loading

“By design, you were basically encouraged to put in as much as you took out,” Koch says.

The types of games people play have also changed, Koch says. While text adventure games such as The Hobbit dominated in the ’80s, today’s gaming world is inundated with open-world titles such as Red Dead Redemption 2, in which simply experiencing the world is often favoured over mastering it.

Stuckey says the level of complexity in games has generally increased to accommodate the influx of information and hints gamers now have access to.

“If you play the big role-playing games where you’ve got multiple narratives and multiple maps running – all of these moving parts – there’s an assumption that you’ve got access to information, that you can find ways to help keep track,” she says.

Stuckey says there are also plenty of players who would never dream of Googling a cheat code or searching for help online – the “purists”, if you will.

Even our understanding of what it means to master a game has shifted.

“People now need to bring something special to the table, like personality and spectacle rather than simple mastery,” Stuckey says. “There’s an amazing Korean World of Warcraft player. He’d mastered everything in the game, so he made a video where he literally takes off all his hard-earned artefacts, representing hundreds of hours of playing, and destroys them … People will watch just for fun.”

Platforms like Reddit and Twitch might not have made gaming too easy, but Koch says they have diminished the level of social connection; posting about a cheat code might not feel as socially fulfilling as whispering Mortal Kombat brutalities to a friend in the schoolyard.

“I’ve reconnected with friends who’ve talked about missing that sense of community and camaraderie – when five or six of us would sit around totally obsessing over parts of a game,” he says. “Even the arcade experience … It’s hard to come by that energy now, that pure connection where everyone doesn’t have a smartphone in their hand.”

Game Worlds is at ACMI, September 18 to February 8, 2026. Tickets via the ACMI website.

Must-see movies, interviews and all the latest from the world of film delivered to your inbox. Sign up for our Screening Room newsletter.