London: It began, as the best type of stories do, with a pair of lost tap shoes.

Calvin Richardson was a teenager in regional Victoria when he arrived at a Billy Elliot audition without his own shoes, only to be loaned a pair by the instructor. Flustered, he did not land his first big role on stage, but that missed chance turned out to be only a small detour.

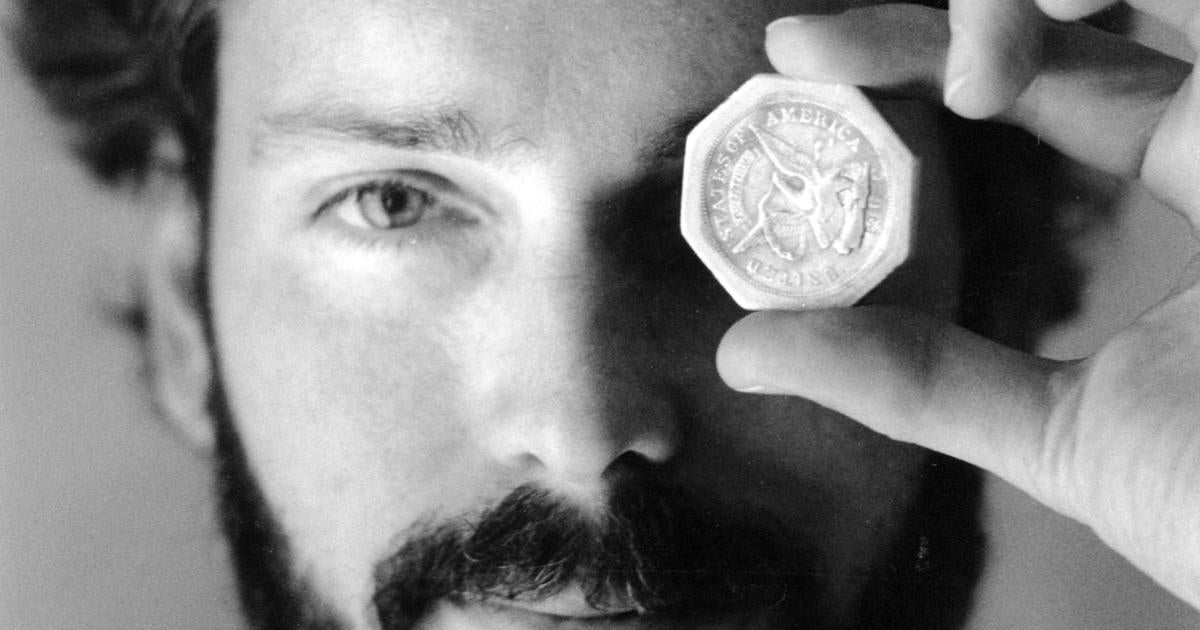

Calvin Richardson, a young ballet dancer from country Victoria, who is now principal soloist at the Royal Ballet.Credit: Tristram Kenton

“I’d lost them, and I was totally panicked, but the person who was instructing us let me borrow his, and I actually fit into his tap shoes,” he recalls. “So I did well in the audition, but they were just like ‘oh, I’m really sorry, you did a great job, but we think you’re going to grow too much’ ... I think I was just about ready to give up and then.”

Now 31, Richardson is principal at The Royal Ballet in London – one of the most prestigious positions in global dance. It’s a long way from his childhood dream of a life in musical theatre, but after more than a decade abroad and a lifetime of discipline and quiet determination, the Australian dancer is reflective on what it means to be at the top and how he got there.

“It feels different,” Richardson says over a coffee deep in the bowels of Covent Garden’s historic Royal Opera House. “There’s a new level of responsibility. You become an ambassador – not just for yourself, but for the company.”

His performances are fewer than in his corps days, but the pressure is greater. “You’re no longer trying to impress the person at the front. The rehearsal is for you. What do you want to do with it?”

To see Richardson on stage is to fully understand why he has risen to the top. Tall, handsome with strong presence and charisma, as Jack/The Knave of Hearts in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland he almost floats across the stage with a smile which disarms.

Since his promotion, the pace has only intensified. At the time we speak, rehearsals for Alice blended into new work for The Statement, a contemporary drama danced to a soundtrack of spoken word, while Cinderella drew in audiences in their hordes. He had spent the past few months wowing in the lead role in Romeo and Juliet – including performances in Brisbane – in a production originally choreographed in 1965 by the legendary Kenneth MacMillan.

Raised in Traralgon, a coal-mining and timber town in Victoria’s Latrobe Valley, Richardson’s path to ballet began at local dance schools and country competitions with the support of parents Jan and John. He learned his trade under Vicky Flowers of Vicky’s Dance Academy in Morwell.

Richardson as Espada in Don Quixote.Credit: Andrej Uspenski

“I just remember picking up my sisters and seeing them do the splits. I thought, ‘I want to try that.’

“Miss Vicky was a great tap teacher. It really spoke to me ... We grew up with a lot of Gene Kelly in Singin’ in the Rain.”

A scholarship to the Victorian College of the Arts Secondary School at 14 changed everything, bringing a greater focus on the ballet discipline, which would eventually win his heart. It meant a pre-dawn, near three-hour train journey from Gippsland a few days a week.

“I think I fell in love with it properly then,” he says. “I mean, I still didn’t have expectations of what I should be doing ... but I just sort of soaked all of that up.”

Richardson in The Statement, a dance-drama choreographed to spoken word which explores the shadowy depths of human nature and boardroom politics. Credit: Andrej Uspenski

Moving across the world as a teenager, he joined the Royal Ballet at 20 after graduating from the prestigious Royal Ballet School, and has never looked back. Over the years, he’s played roles from the Mad Hatter to Romeo, across stages in New York, Japan and Madrid.

A typical day now in London starts with class at 10.30am, followed by rehearsals and performance that can stretch late into the evening. The routine mirrors that of elite athletes: injury management, recovery and mental health are constant priorities

“I’ve had my fair share of injuries,” he says. “So I’ve learned to listen to my body more.”

While he’s “not a yoga person”, breath work has become a grounding practice. “There’s a dancer here who runs breath classes. When I’ve joined, it’s really helped slow things down.”

Kevin O’Hare, artistic director of the Royal Ballet, has watched Richardson’s rise with admiration.

“Calvin has that rare ability to move between classical and contemporary worlds with total commitment,” O’Hare says.

In a company with a diverse repertoire, from MacMillan classics to commissions from Canadian choreographer Crystal Pite, versatility is essential.

“Every time a new choreographer comes in, I say, ‘There are 103 dancers, take your pick.’ And they gravitate toward Calvin. He brings something alive in the room.”

Richardson’s adaptability is matched by his work ethic.

“When you leave school as a standout, it’s easy to expect things to happen quickly,” O’Hare continues. “But Calvin started from the corps, took every role seriously, and never lost that focus.”

Richardson’s resilience is particularly notable among the many Australians at the Royal Ballet.

“They’ve left home, left their families,” O’Hare says. “They’re not going to waste the opportunity. Calvin’s one of those – you can see he’s here to make it count.”

Leanne Benjamin, one of Australia’s finest ballet exports who spent two decades as principal dancer in London, says the nation has always punched above their weight courtesy of historical and cultural connections.

“The real leap is coming from some place rural, or isolated, and being thrown into an intense kaleidoscope of change, senses, otherness,” she says. “And what Calvin brings with him is that he is his own person, and you can see that on stage in everything he does.” Benjamin, who hails from regional Queensland, said while Richardson was “technically brilliant” he was “a singular person”.

“And because of that, he stands out. That’s why choreographers, dancers, critic and audiences adore him,” she says.

For Richardson, the craft goes beyond technique. “Take the Mad Hatter,” he says. “The first time, I had to push myself to go far with the expressions, to be silly in front of friends. That’s weirdly vulnerable.”

Other roles, like Romeo or in Manon, demand more restraint. “You might spend a long time just rehearsing how to walk into a room because of what your character has just seen or felt.”

Without dialogue, everything depends on intention. “There’s this beautiful ambiguity – what are you saying with that look, that movement? You find a lot of meaning in those moments.”

He’s especially drawn to the classics. Still, he admits he sometimes feels like an outsider to ballet history. “I wish I knew more. But maybe that perspective has its own value.”

As a teenage boy in regional Australia, the challenges were real – especially coming to terms with his sexuality. He admits he nearly quit dancing because he was struggling going into senior school.

“I didn’t know I was queer at the time, but I was very different,” he says. “I didn’t have the language to articulate that, but ... I was sort of leading a double life. I was dancing, but I was keeping that secret, like, out of fear of being bullied.”

Richardson says his journey as a queer artist has deeply influenced his performances. It has earned him an added following in the UK, where he recently posed for a spread in Attitude magazine, an LGBTQI publication.

Calvin Richardson and Meaghan Grace Hinkis in the Royal Ballet’s production of Alice In Wonderland.

He says embracing his sexuality has played a significant role in his approach to contemporary works, where he has the freedom to express himself authentically. He says these roles allow him to bring parts of his identity to the stage, whether through nuanced physicality or emotional depth.

He’s portrayed several queer roles, such as in Yugen and Woolf Works – both pieces by Sir Wayne McGregor.

“Performing queer roles feels natural,” he says, explaining how his movements are often informed by his own experiences, allowing him to bring a unique depth to these characters. For him, these roles offer a chance to connect with audiences on a more personal level.

His journey of self-acceptance has shaped not only his art but also his approach to performance.

“I now feel more confident in my identity,” he says. This sense of freedom on stage enables him to embrace imperfections and trust in his talent, all while continuing to challenge traditional norms within classical dance.

When asked what he’d say to his younger self, the kid who thought he should hide his passion for dance, he pauses. “I’d probably say: Like, I understand how painful this is, but also you can still do this, that you’re loved and you’re cared for and all those things.”

Richardson is aware that not everyone gets that chance. Many aspiring dancers are lost before they begin.

“This is a short moment,” he says. “I want to plan around that, perform for family, bring things full circle ... You rely so much on your body.”

O’Hare notes that dancers today face more pressure than ever: greater versatility, public visibility, and the emotional toll that comes with it. Yet, he believes dancers like Richardson shape the future of the art form.

“Calvin’s a role model, not just for the company, but for dancers everywhere,” O’Hare says.

And he never forgets his shoes.

Most Viewed in World

Loading