Tyler Robinson was 22 when he allegedly walked into a Turning Point USA event at Utah Valley University on September 10, 2025, and shot Charlie Kirk dead.

His case is now emerging as an example of how, when offline structures unravel and online life fills the gap, radicalisation can hide in plain sight. Robinson, according to US officials, dropped out of college, withdrew from stable social anchors and spent increasing amounts of time in online spaces.

Discord, Reddit, gaming forums and meme chats served as virtual fuel for the alleged real-world violence that later followed.

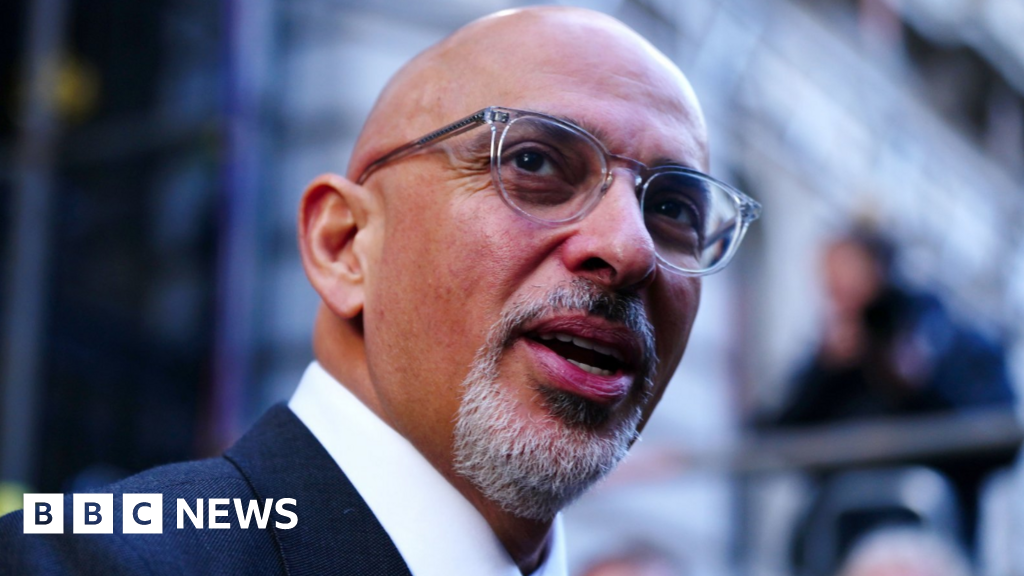

Tyler Robinson was 22 when he allegedly walked into a Turning Point USA event at Utah Valley University on September 10, 2025, and shot Charlie Kirk dead. Credit: AP

Utah Governor Spencer Cox said Robinson “came from a conservative family but held opposing beliefs” and that online communities had shaped him over several years. Cox said social media played a “direct role” in what he described as a “political assassination”. Robinson is now facing seven charges, including capital murder, aggravated firearm discharge, obstruction of justice and witness tampering, and Utah prosecutors have announced their intent to seek the death penalty.

The motive behind Robinson’s alleged act remains complex, but evidence uncovered from the shooting referenced his online life, a physical reflection of the virtual. He was what Gen Z refers to as “terminally online”, a term for someone who spends so much time on the internet that their online reality becomes detached from, and more important than, their real-world life. Bullet casings from Robinson’s gun were found to be engraved with an assortment of messages, from anti-fascist slogans to game-culture references and meme subculture phrases. Investigators also allege Robinson sent messages on Discord shortly before his apprehension: “It was me at UVU yesterday. I’m sorry for all of this,” he allegedly told a group chat of more than 20 people.

From left; Discord CEO Jason Citron, Snap CEO Evan Spiegel, TikTok CEO Shou Zi Chew, X CEO Linda Yaccarino and Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg at a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing in Washington.Credit: AP

For people unfamiliar with the digital world Robinson inhabited, Discord can seem opaque. Launched in 2015, it began innocently enough as a free voice-and-text chat service for gamers. It skyrocketed in popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic into a sprawling social platform used by more than 200 million people each month. It is built around “servers” – private or public chat rooms that can be organised around anything from video games to chess clubs, music fandoms and extremist politics.

Many servers are small, invite-only groups where outsiders have no visibility. That structure makes Discord popular with young people who want semi-private spaces online, but it is also attractive to communities that push disinformation or extremist content out of sight of traditional moderation.

Discord has denied that it has evidence Robinson used the platform to plan the assassination. But despite the denials, an examination of Robinson’s online life points to a broader pattern of radicalisation through memes and online forums that researchers have long warned about.

Pepe the Frog was plucked more than a decade ago from the relative obscurity of the Myspace-sprung slacker-life comic Boy’s Club. It’s now a right-wing internet meme.

The company did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Kirk’s death has spurred a US House committee to summon the chief executives of Discord, Steam, Twitch and Reddit to testify about the role their platforms may play in radicalising their users.

“Congress has a duty to oversee the online platforms that radicals have used to advance political violence,” committee chair James Comer said in announcing the October hearing. Discord said it “welcomed the opportunity to testify” and that it was committed to engaging with policymakers.

This online-to-offline pipeline is not hypothetical.

The Institute for Strategic Dialogue, perhaps the world’s leading think tank on fighting online extremism, recently released a report Young Guns: Understanding a New Generation of Extremist Radicalisation. It paints a picture of a shifting landscape: young people increasingly come to extremism not through ideological pamphlets or formal recruitment, but through meme culture, humour, gaming communities, small private chat rooms and algorithmically mediated echo chambers.

Loading

The report found that exposure to extremist content, when delivered in glossy “memeified” packages, combined with real or perceived social isolation, identity uncertainty, or offline disruption, can gradually normalise extremist rhetoric and symbols.

Most never do more than post or comment. But a tiny minority escalate. And Robinson appears to have been one of them.

In 2021, Discord reported banning more than 2000 extremist communities in a six-month period, including those associated with the “Boogaloo” movement and QAnon conspiracy, after detecting rises in violent activity in the US. Many forums were also removed after direct involvement in incidents such as the US Capitol riot, in which rioters communicated extensively on Discord servers before and during the attack.

In Australia, recent high-profile operations show extremist recruiters targeting young gamers, crafting digital recreations of terrorist events and seeding far-right content in games such as Fortnite and Minecraft, then propelling those ideologies across Discord and wider social media. The Five Eyes intelligence community published a joint report in December 2024 warning that youth radicalisation via online platforms was growing at an alarming pace.

The problem is stark: every Australian counterterror case in 2024 involved a minor or a young adult, according to ASIO.

Neo-Nazi groups such as the National Socialist Network have also used Telegram and encrypted chats to recruit in Melbourne and Sydney. ASIO chief Mike Burgess has repeatedly said “extreme right-wing groups” are using online platforms to recruit teenagers.

Neo-Nazi leader Thomas Sewell at the March for Australia rally.Credit: The Age

The Christchurch shooter – an Australian – was radicalised online and streamed his massacre on Facebook.

That livestreamed mass killing led to the Christchurch Call, a collaboration between governments and the tech industry designed to remove extremist content in a co-ordinated fashion.

Six years later, it’s clear those efforts have not worked. The video of Charlie Kirk’s assassination generated millions of views on YouTube, X, Instagram and other platforms, while Tyler Robinson appears to be the latest alleged murderer to emerge from the “terminally online” world.

Matt Quinn knows this world from the inside: he was once a white supremacist gang leader in western Sydney. As a teenager, he carried crowbars, led gangs and began to embrace extremist ideology, before eventually pulling away. He now leads Exit, a deradicalisation program helping young people leave far-right networks.

He says far-right recruiters are exploiting whatever platforms are most popular with youth – TikTok, Reddit, Discord – and that a pattern of humour, memes and inside jokes can lead to small acts of participation before gradual escalation.

Teenagers become useful amplifiers because they’re digitally savvy, socially fluent and able to blend into youth culture in a way older organisers cannot.

Andre Obler, chief executive of the Melbourne-based Online Hate Prevention Institute, describes online radicalisation as a mix of human and technological forces: “People are getting into communities, echo chambers where claims may or may not be true, and they’re being used to rile up emotions. People find belonging, and it bounces off each other, getting more and more extreme.”

Andre Obler, chief executive of the Melbourne-based Online Hate Prevention Institute.

He points to the example of Charlie Kirk’s alleged murderer: one side claims he was a radical leftist, the other side claims he was on the far right, and each group has its own narrative leading to further polarisation.

Algorithms feed this cycle by pushing users towards content that confirms their worldview, while filtering out dissenting views.

“There’s a growing lack of faith in governments, in the system, and in laws, that people feel like they can just take the law into their own hands. I think that starts as a feeling online of ‘I can do what I like’, and then some of that gets carried into the real world, where it turns into violence,” Obler says.

Obler says Australia’s eSafety Commissioner is doing positive work in this space but that it needs more resourcing. “There needs to be a deputy commissioner or someone who is specifically dealing with these issues of extremism and hate speech online,” he says.

Charlotte Mortlock, founder of Hilma’s Network in Australia, a group that focuses on grassroots recruitment of women into the Liberal Party, says many young Australians are realising that people “don’t hate each other” intrinsically, but that they have been “led down this extreme, radical and combative path for the sake of tech bros’ profits”. Hilma’s Network has conducted polling with Resolve showing that most young people now “want out” of social media algorithms. They can feel themselves being manipulated and they want more transparency.

Charlotte Mortlock from Hilma’s Network.Credit: Edwina Pickles

“Algorithms are an assault on freedom of speech. They censor, silo and polarise,” she says.

The polling is clear in favour of algorithmic transparency: for platforms to be upfront about why a certain piece of content is being recommended, and for researchers and regulators to gain access to test how algorithms actually behave in the wild.

It’s clear that despite the best intentions, parents, governments, regulators and the platforms themselves are playing catch-up.

Solutions exist, but none are simple. Quinn says deradicalisation works best when it avoids direct confrontation. “Not challenging people’s ideas until they’re starting to challenge them themselves”, he says, is key. Only then can psychologists and counsellors help uncover the personal traumas or identity crises that drew people in. “Is it just belonging? Is it purpose? Is it childhood trauma? You have to understand the why before you can pull them out.”

Offline supports matter, Quinn says. Research consistently shows radicalisation feeds on loneliness and disconnection as much as ideology.

Greater transparency from tech platforms is another solution: researchers and regulators still lack meaningful access to the data behind algorithms, leaving independent audits almost impossible. Advocates say Australia’s coming under-16 social media ban is likely to be a step towards protecting young people.

Australia has one distinct real-world advantage over the US, according to Obler: gun laws. “The main difference between us and the US really is about access to guns,” he says. “After Port Arthur, the gun buyback and restrictions reduced firearms in the community. That is the deciding factor that makes Australia safer than the US.”

Robinson’s case is still under investigation and many details remain murky. There is already the inevitable debate over whether Robinson was “radicalised by Discord”, or whether ideology, mental health or grievance drove him. But less debatable is the infrastructure – algorithms, meme culture and private online spaces – that enabled radicalisation to be both possible and potent.

Loading

For Mortlock, Quinn and others, the killing of Charlie Kirk is not just a tragedy of one man’s death – it is another warning shot that regulation of platforms and algorithms is needed, as well as more investment in digital literacy, youth wellbeing and real community more broadly. Only then might the invisible pathways of radicalisation begin to be illuminated and weakened.

The Business Briefing newsletter delivers major stories, exclusive coverage and expert opinion. Sign up to get it every weekday morning.

Most Viewed in Technology

Loading