By Alexandra Sangster

January 11, 2026 — 5.30am

I am picking up sodden scraps of decomposing plastic, from a gutter, by the side of the road. It is the middle of the day, hot now, and I still have my bike helmet on and my headphones in. I am a little

overwhelmed.

I have just come from a shift as an emergency chaplain with the Victorian Council of Churches Emergencies Ministry. I am on my way home. But then I see them – the flowers, wrapped with ribbons. Beautiful and bright, laid on the footpath where the boy was shot.

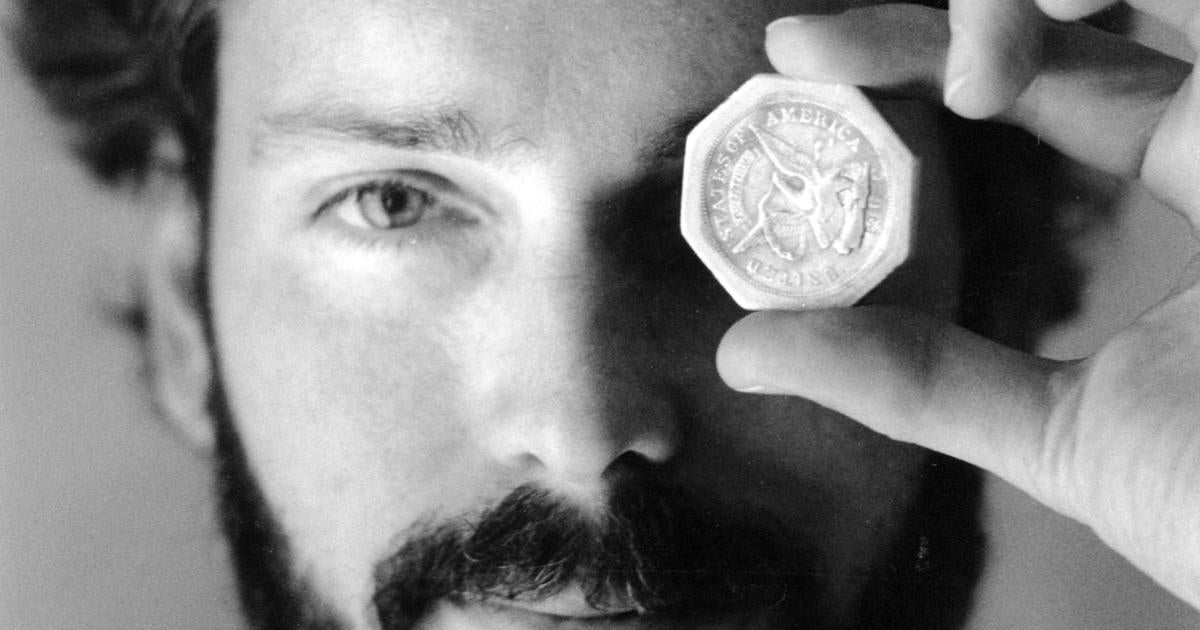

Flowers left in Fitzroy, to remember a boy killed on the street.Credit: Wayne Taylor

It is a narrow street, like a thin artery shooting out from the main vein of the road, and there is not much on it but the sides of buildings, a bluestone church and the flowers, all bright and beautiful and lying in filth.

An hour earlier, I had been sitting with another chaplain – a large man with a flowing beard, a member of the God Squad who has spent his life ministering on the street and in the jail cells.

We were sharing war stories, recalling funerals where ancient mothers had clutched our hands and not let go, and where fathers had delivered eulogies to congregations of weeping trans kids and bikies alike.

Funerals where family members who had not spoken for 20 years had sat separated – a sister on one side of the church, a brother on the other – and funerals where we have seen the ghosts of the dead hover by the coffin mist like when the members of the family came down.

They had been gathering here with the father of the boy who had been killed, and now they came from the flats to meet us. They are tall, so very tall and so very dignified. And so, so broken.

There were no words.

We stood in silence, and I reached out my hand. Such an intimate thing – a handshake. Like a promise. I mean you no harm, we are saying. I have no weapons, we are saying. We are good, we are saying – all of us – and we will show up for one another when we can.

“How is the father?” I ask.

“He will not be alone,” they told me. “He will not be alone.”

And now I am here, picking up a discarded COVID mask, one blue plastic glove, and a rotting sheet, making space for a memorial for a boy now gone. There is something deeply necessary about this mucky work, it cannot not be done, and yet it also feels conspicuous and ridiculous in equal measure.

How me putting my hands into this drain of sodden detritus helps the father or the soul of the boy is unclear, but I can’t not do it.

When I am finished, I turn my bike toward home and hear a man yelling at a puppy. The dog is tiny and exhausted and the man is cursing at him, lifting him by the lead from his neck.

“Stand up,” he yells. “Stand up.”

I take off my helmet and rest my bike against a pole.

“Can I say hello to your pup?” I ask, and immediately he softens.

“Yeah,” he says. “Yeah.”

“What’s his name?”

“This is Charlie.”

“Charlie’s only a baby,” I tell him. “He’s going to get tired. It’s OK for him to sleep.”

“Yeah, yeah,” the man nods, then picks up his dog and runs for the tram.

A woman walking past – clean as a daisy, with bright, clear eyes – says, “Thank you. Thank you for saying something. I was afraid. I didn’t know what to do.”

“Just say something,” I offer. “But say it with love. That usually works. But always say something, if you can.”

I realise I’m beginning to preach. It is definitely time to go home.

I take one last look up at the towers, where the father sits, in his terrible, terrible grief and I bow my head, for just a moment and then take the lanyard from around my neck and ride off, into the heat of the day.

Alexandra Sangster is a minister, facilitator and Darebin councillor.

Most Viewed in Lifestyle

Loading