When that account was closed, the funds were moved to accounts with new aliases – Luigi Locarno, run by Gallagher, and Keith McKaskill, linked to Wallace.

“In the application form Lester Normans gives his date of birth as 20th September 1932 which is the same date as Mr. Gallagher’s. Clearly Normans is Gallagher,” Sharp wrote.

“The manner in which these funds have been spent is yet to be examined. Certainly, money has been spent and the amount left for the benefit of members is greatly reduced.”

Gallagher was tasked with securing members’ funds for safe keeping. Minutes obtained by Sharp show the secretary told a branch meeting in April 1987 that he “would rot in jail before he would give the funds up for the government”.

“Mr. Gallagher then claimed there was a security problem and that most likely the meeting room was bugged. He therefore indicated that he would not divulge the whereabouts of the funds unless directed by a majority of the meeting. ”

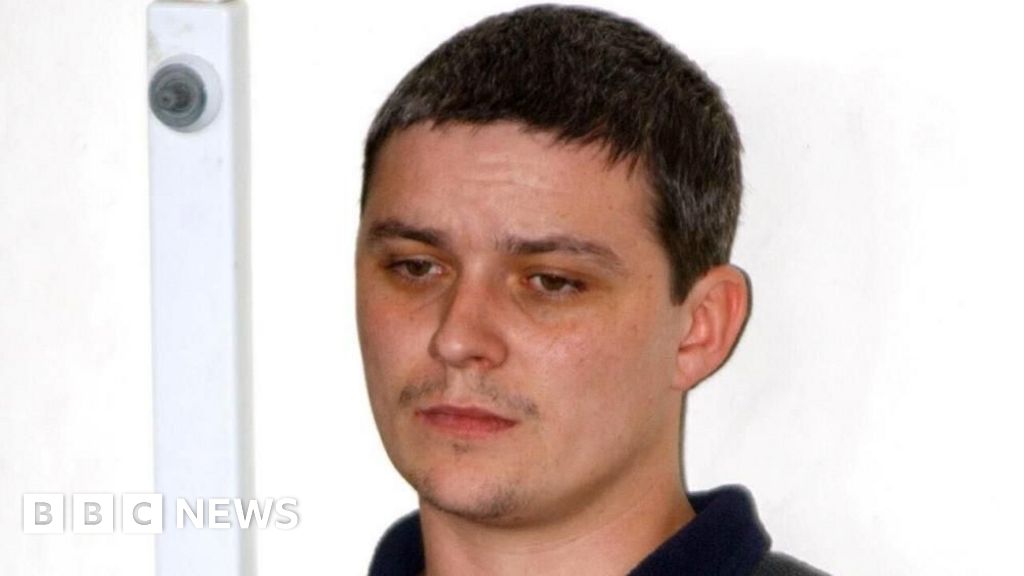

Norm Gallagher, secretary of the BLF, in Melbourne in 1984.Credit: Michael Rayner

But one of the most brazen moves by the BLF came months later, on October 13, 1987 – the day Sharp received authorisation to raid the union’s headquarters.

Four hours after police had visited the Lygon Street building, about $766,000 was transferred to Western Australia. This defied the order authorising the raid and the seizing of the union’s assets.

In an article published in The Canberra Times on October 21, Gallagher bragged that the cash had been withdrawn and taken to a place “safer than Fort Knox”.

“It was done for two reasons: one was we thought we’d give labour minister Steve Crabb enough rope to hang himself as he was gloating over the raid,” he said.

Loading

“And secondly, we had to give our own people enough time to have that money removed.”

In his report to cabinet, Sharp agreed that the Victorian branch was essentially the power base of the BLF, but noted its membership had fallen. He estimated that by the time of the raid, it had about 600 financial memberships with another 400 “honorary members”.

Sharp concluded that, putting aside whether the BLF leadership was fit to follow industrial relations rules, the erosion of memberships and finances meant the union was unlikely to serve its intended purpose soon or “be able to play any worthwhile role in the industrial relations of the Australian building and construction industry”.

By 1994, the remnants of the BLF were eventually merged into the CFMEU, and many assets were frozen by the government and not released until 2002. Most of the accusations throughout the saga never ended in charges.

The echoes of the BLF’s financial manoeuvres continue today as the CFMEU’s administrator fights a brazen move by former CFMEU bosses to regain control of a secret $1 million election slush fund.

The turmoil follows the exit of long-time secretary John Setka, who was forced to resign in July 2024 after revelations the CFMEU had been infiltrated by underworld figures and bikies were published. An independent administrator was subsequently appointed by the federal government.

Setka has since been charged by Victoria Police’s Taskforce Hawk over allegations of attempting to threaten or intimidate the government-appointed administrator.

The taskforce was created to probe multiple areas of concern around corruption and organised crime in the building sector.

The newly released cabinet papers also reveal the labour hire sector was a primary concern for the Cain government, mirroring the systemic issues currently plaguing the Allan government.

In December 1983, a state government committee investigating cash-in-hand and pyramid subcontracting schemes warned that hundreds of millions of dollars were being paid untaxed on Victorian sites annually. Field investigations across 54 projects found the practices on all but three. Of those projects, 39 were run by government departments or authorities.

“Some contractors informed the committee that they faced no alternative but to either leave the field of work to those contractors engaged in avoidance practices or copy their example,” the 1983 report found.

Former CFMEU head John Setka.

The committee recommended long service leave be extended to the entire sector, and for departments to have greater oversight that its projects were complying with the law.

Forty years later, the challenges surrounding labour hire and subcontractors in Victoria remain.

Loading

In the last week of parliament for 2025, the Allan government passed laws giving the Labour Hire Authority stronger investigation powers and the ability to impose tougher tests on fit and proper people who are registered.

These changes follow a series of arrests and raids over allegations of corrupt payments of labour hire firms on state government building sites, with labour hire emerging as a key contemporary issue at the centre of corruption on construction sites.

Victoria’s corruption watchdog wants “follow-the-money” powers, which would allow it to pursue taxpayer funds that make their way through these extra levels of payments.

Government policy and contractual requirements that took effect from January 1 require contractors to report criminal and unlawful behaviour they observe on state-funded projects.

The government has established the Construction Complaints Referral Service, designed as a central hub for reporting industry misconduct.

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.