This story is a part of our series exploring the benefits and cost of vitamins to our health and hip pocket.

See all 6 stories.Dairy is such a staple in Denmark that even the rampaging Vikings kept cows and churned butter back in the 8th century. But it wasn’t until World War I that the Danes appreciated just how precious their butter was.

Known for its superior quality, Danish butter was in great demand around Europe, driving the price of it so high that dairy farmers could no longer afford to eat it. Searching for a cheaper alternative, they turned to margarine.

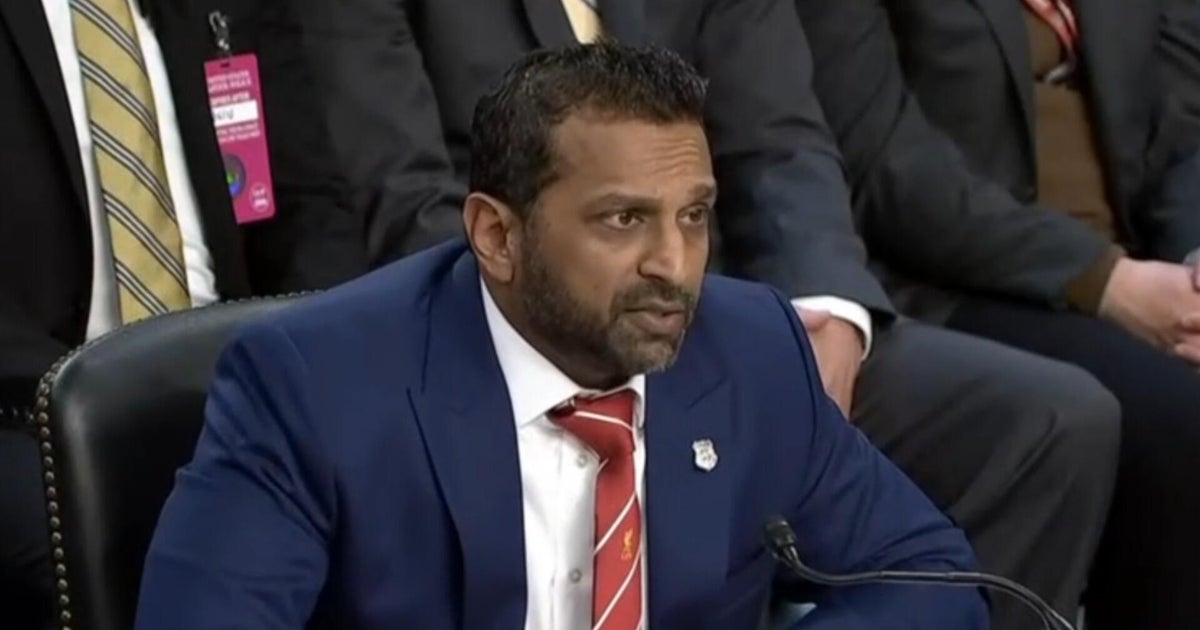

What’s inside your pill may not be as “natural” as you think.Credit: Aresna Villanueva

A French invention, margarine was originally made from beef tallow and skim milk and, later, the tallow was replaced with margaric acid containing vegetable oil.

Margarine suddenly took over as the staple of the poorer Danes’ diet for less than half the price of the butter they were exporting for the king’s royal bread. For a time, they were the world’s biggest consumers of margarine, eating about 20 kilograms per person each year.

That was until mysterious health issues that began to affect rural infants, orphans and the destitute. Cases of ulcerated eyes and children going blind began occurring in Denmark at an alarming rate.

As doctors worked to figure out what was causing the blindness, World War I was in full swing. It was 1917 and German ships had created a blockade in the North Sea, cutting off supplies to Britain. Denmark could no longer export its butter, nor could it import the vegetable oils it needed to make margarine.

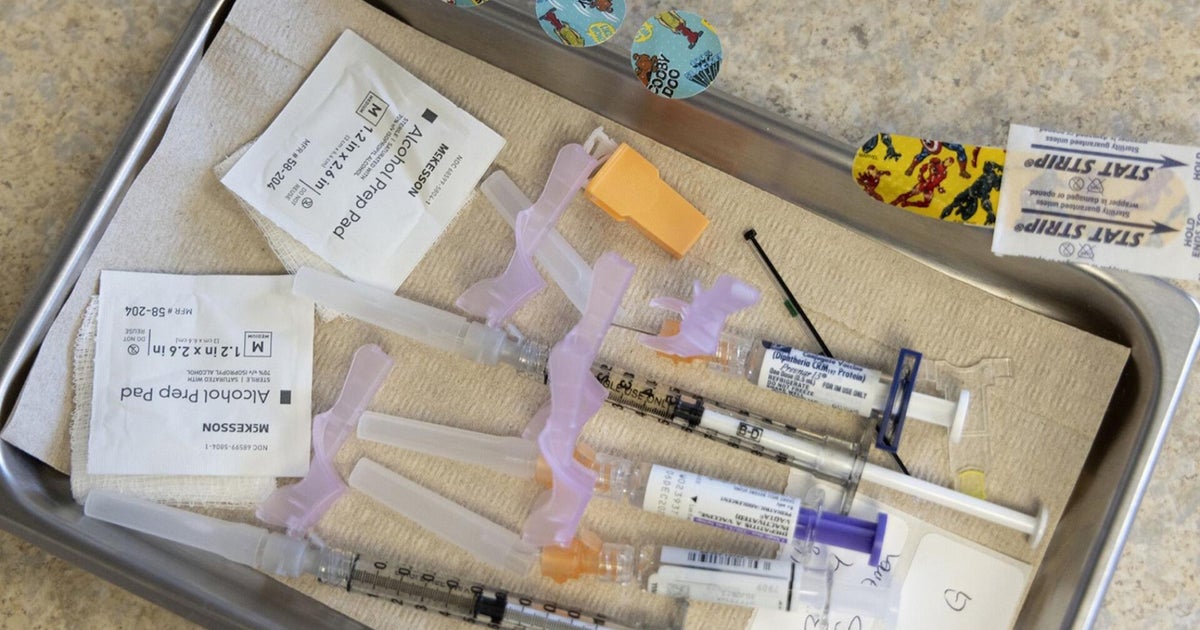

We now know a lot about what is in our foods, but what about our vitamin pills?Credit: Getty Images

The Danes returned to eating butter and soon the eye disease epidemic ended. It had been an unwitting “great dietetic experiment involving a whole nation” and it showed a substance in butter and milk – which researchers later identified as vitamin A – could save sight.

Today, we know a lot about what’s in our food. But what about what’s in our vitamin supplements? And how do you choose between them?

“Marketing plays a significant role in shaping public confidence in supplements,” says accredited practising dietitian and nutrition researcher Danielle Shine. “Brands often position their products as essential for ‘wellness’, anti-ageing, or disease prevention – areas that are emotionally charged and difficult to regulate.”

Those messages are amplified by glowing, genetically blessed celebrities who wouldn’t think of putting anything “nasty” inside their bodies. And so many of us assume our vitamins are pure and full of natural goodness.

The reality is more complex.

What is in your vitamin?

Vitamins and supplements can be produced in various ways: extracted from plants or animals, or synthesised from chemical compounds in a laboratory.

Loading

Synthetic vitamins can be made from petroleum extracts, coal tar derivatives, and chemically processed sugars, which are then purified to eliminate contaminants.

“Industrial synthesis or microbial fermentation provides a more scalable, cost-effective, and reliable way to produce vitamins that meet strict standards for purity, potency, and affordability,” says Shine.

Though chemically identical in structure, we can’t make generalisations about whether natural or synthetic vitamins are better. There are still limitations in the research about how our bodies absorb synthetic versus natural vitamins. It can also depend on the particular vitamin.

For example, there is comparable bioavailability for natural or synthetic B vitamins and vitamin C, whereas natural vitamin E has roughly twice the availability of synthetic vitamin E. Synthetically produced folic acid is more bioavailable than naturally occurring folate as is retinol from animal sources or derived from chemicals versus beta-carotene from plants.

“Many vitamins are derived from those kinds of chemical sources, but aren’t inherently worse than ones derived from natural sources,” says Kamal Patel, a nutrition researcher and co-founder of Examine.com. “There’s a lot that isn’t known about the health effects of different processing techniques, so it’s difficult to paint things with a broad brush here.”

The source of a starting compound doesn’t mean anything in itself, adds Oliver Jones, a professor of chemistry at RMIT; it is the final product that counts.

You get more from the fruit, but when it’s broken down vitamin C from an orange is the same as from a lab.Credit: Getty Images

“The final product is still vitamin C or D, etc, and is chemically identical to the ‘natural’ version,” Jones says. “Vitamin C from an orange is the same chemical as vitamin C synthesised in the lab.”

The dose of the vitamin also alters the effect it has on us and can vary widely depending on the product. As we have seen with recent cases of vitamin B toxicity, the dose in the bottle can exceed our requirements by 100- or 200-fold.

There are legitimate clinical reasons why higher doses may be included in some products, says Associate Professor Dr Joanna Harnett from the University of Sydney’s School of Pharmacy.

Loading

Those reasons include preventing and treating a diagnosed deficiency, addressing increased needs due to medical conditions (for example, malabsorption, or genetic conditions), or offsetting nutrient depletion caused by certain medications. Still, she adds that stricter regulations around dose are needed, and high doses should only be taken under the supervision of a doctor.

Synthetic or natural, most contain ingredients not listed on the packaging. Excipients are the inactive ingredients such as coating agents, colours, dyes, fillers, flavours and sweeteners that act as binders, diluents, lubricants, disintegrating agents, plasticisers, solvents, stabilisers and emulsifiers, as well as improving the taste, bioavailability and texture of the product.

“Only active ingredients need to be listed on the label and excipients like binders, fillers and preservatives don’t have to be publicly listed unless they are known allergens or substances of concern,” says dietitian and nutrition research scientist Dr Tim Crowe.

In the doses they are used, most excipients are most likely very low risk, Crowe adds. However, it does remove the principle of informed choice and, he says, there might be some people who could still have sensitivity reactions.

What your vitamin does not always contain

Supplements do not always contain quality, effective or safe ingredients. In fact, sometimes they don’t contain what is on the label at all.

One 2022 study analysed 30 different immune health supplements only to find that 17 had inaccurate labels, 13 of which listed ingredients on the label that were not detected in the product.

Nine products had substances detected that were not mentioned on the label, including adulterated substances that could potentially cause harm.

A similar issue was detected in a separate analysis of brain health and cognitive supplements, leading the paper’s authors to conclude that “product labels may be deceiving and could put the public at risk”.

A 2023 study of melatonin gummy supplements found that 22 of 25 contained different amounts than what was listed on the label. The same issue arose in a recent test of multivitamins. More than a quarter of the products contained different levels than their labels claimed.

What’s on the label and what’s in the jar are not always the same.Credit: Getty Images

How to choose between them?

A “quality brand” according to the experts is one that tests its products regularly to ensure it contains what the label says.

Claims about greater bioavailability, methylation or revolutionary new forms should be treated with caution.

Methylated vitamins, for instance, are primarily intended for people with certain genetic variants (like MTHFR polymorphisms), which may impact vitamin metabolism.

“However, the evidence supporting widespread use of methylated vitamins remains limited, inconsistent, and largely theoretical,” says Shine. “There’s no strong reason for most people to opt for these more expensive versions.”

With huge differences in the quality, price, dose and form, let alone the decision paralysis that comes with thousands of options on the shelf, how do you choose?

Patel doesn’t envy the decision-making process anyone without a science degree has to make.

- Avoid hyped-up claims: “It’s typically better to choose companies with a high degree of transparency and without over-the-top claims,” he says.

- Opt for Australian made, TGA approved and clear labelling: A product should list all of its ingredients and the amounts, including the specific form of each nutrient, Shine says.

- Talk to your doctor: If a product has 10 times your requirements, consult your doctor to find out if you need that much, suggests Jayashree Arcot, a professor in Food Science and Nutrition at UNSW: “You would need a blood test to know if you really need that much.”

- Consult the pharmacist: They are generally knowledgeable about the different brands, Arcot says.

- Check the dose: Jones doesn’t take any supplements because he does not have a deficiency. “If I did take something, on medical advice, I’d look for something that did not have 100 per cent of the recommended daily amount so that I would still get most of my vitamins from my diet.”

- Go for a single: If you do need a supplement, buy it as a single supplement, advises Evangeline Mantzioris, program director of Nutrition and Food Sciences at the University of South Australia. “If you need iron, I would get straight iron. I wouldn’t go for a multi-supplement – ever. You run the risk of getting toxic levels.”

- More expensive doesn’t mean better: “I just buy the cheapest one,” Mantzioris says. “I would rather spend the money on a good piece of cheese or chocolate. It’s a lot of money. Imagine the exotic fruits you could buy.”Make the most of your health, relationships, fitness and nutrition with our Live Well newsletter. Get it in your inbox every Monday.

Most Viewed in Lifestyle

Loading