Echo Kopplin wants South Dakota's leaders to know that money from a new $50 billion federal rural health fund should help residents with limited transportation options.

Kopplin, a physician assistant who works with seniors, low-income people, and mental health patients in the rural Black Hills, shared her thoughts at a meeting hosted by state officials.

South Dakota's leaders did a "good job of diving in" and asking questions to get "deeper at the root of the problem," she said.

Kopplin later told KFF Health News how one of her rural patients recently missed two appointments because of a broken-down car and no access to public transportation.

Nationwide, health care workers like Kopplin and thousands of others — from patient advocates to technology executives — flocked to town halls or online portals during the seven weeks state leaders had to craft and submit their applications for the Rural Health Transformation Program to the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. That deadline was Nov. 5.

"We will give $50 billion away by the end of the year," CMS Administrator Mehmet Oz said Nov. 6 at a Milken Institute event in Washington. He said all 50 states had submitted applications.

The program will "allow us to right-size the health care system," Oz said, adding that innovations from the rural work "will spill over to suburban and urban America as well."

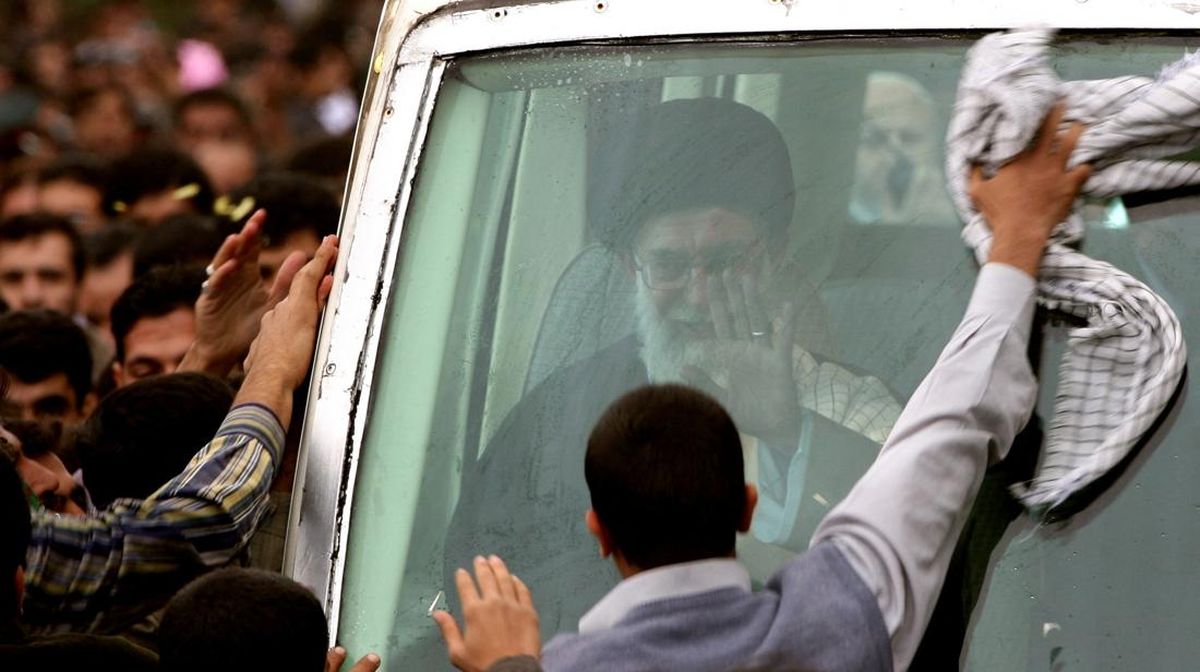

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Mehmet Oz (right) with FDA Commissioner Marty Makary (center) and Esther Krofah, executive vice president of Milken Institute Health, at a Milken Institute event on Nov. 6, 2025.

Sarah Jane Tribble/KFF Health News

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Administrator Mehmet Oz (right) with FDA Commissioner Marty Makary (center) and Esther Krofah, executive vice president of Milken Institute Health, at a Milken Institute event on Nov. 6, 2025.

Sarah Jane Tribble/KFF Health News

Among applications and summaries publicly shared by states, themes include workforce development, telehealth, and access to healthy food. In Kansas, leaders want to build a "Food is Medicine" program. Wyoming officials propose a new program called "BearCare," a state-sponsored health insurance plan that patients could use only after medical emergencies.

But many health policy experts and Democrats are raising alarms that the Republican-backed program will become a "slush fund." Critics worry it will fail to reach the small-town patients they say need it most, especially as states face nearly a trillion dollars in Medicaid spending reductions over the next decade. Medicaid, a joint federal-state program, serves nearly 1 in 4 rural Americans.

"The status quo is tremendous distress in rural communities," said Heather Howard, a professor of the practice at Princeton University and director of the university's State Health and Value Strategies program, which is tracking the rural health fund. The new funding won't be enough to offset the Medicaid losses, she said.

Congressional Republicans added the five-year, $50 billion Rural Health Transformation Program as a last-minute sweetener to President Donald Trump's massive tax-and-spending legislation. The move helped win support for the One Big Beautiful Bill Act from conservative holdouts who worried that the Medicaid cuts in the bill would harm rural hospitals in their states.

In Montana, which hosted an online public forum before submitting its application, a nonprofit director pitched youth peer support as a way of battling high suicide rates. A registered nurse asked state leaders to "think maybe even bigger" and consider statewide universal health care.

And in Georgia, a technology-focused chain of primary care clinics that serves seniors proposed expanding its operations into that state in its online public comment. A rural grant writer asked for "safe and stable housing."

The law says half of the $50 billion will be divided equally among all states with an approved application. The rest will be doled out according to a points-based system. Of the second half, $12.5 billion will be allotted based on each state's rurality. The remaining $12.5 billion will go to states that score well on initiatives and policies that, in part, mirror the Trump administration's "Make America Healthy Again" objectives.

Top Senate Democrats have raised alarms about the rural health program. They include Ron Wyden of Oregon and Tina Smith of Minnesota, who called on a federal watchdog agency to investigate the fairness and implementation of the fund. Taylor Harvey, a Wyden aide, said the Government Accountability Office has confirmed it will investigate.

According to the federal statute, no less than a quarter of states with an approved application may share the second half of the funding each fiscal year, CMS spokesperson Catherine Howden said. The agency plans to publish summaries of approved state projects, according to CMS guidance.

A handful of conservative-leaning states — including Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma — have already instituted regulatory and legislative initiatives, such as prohibiting "non-nutritious" foods in benefit programs, that garner additional points in the program application process.

Michael Chameides, a county supervisor in rural New York, said he fears the money could "be used in ways that would hurt certain states or reward certain states." Chameides is also the communications and policy director with the Rural Democracy Initiative, a national advocacy organization that released a rural action report last month.

Edwin Park, a research professor at Georgetown University's Center for Children and Families, said federal lawmakers gave Oz and his agency "really excessive discretion" when awarding the money.

Federal administrators have added rules that aren't within the statute that created the program, Park said. For example, its application guidelines say states cannot use more than 15% of their funding to pay providers for patient care — payments that are expected to take a hit due to the Medicaid cuts.

Georgetown's health policy experts and Democrats aren't the only ones with concerns. Some Republicans and small hospitals in Ohio worry the money will go to large health systems instead of smaller, independent hospitals that serve people within their rural communities.

CMS' Oz repeated the idea of getting "big hospitals to adopt smaller institutions" at the Washington gathering after applications were filed. He used similar language at a rural health summit hosted by South Dakota-based Sanford Health. "How do we get big hospitals to adopt smaller hospitals? Not to take them over, but to keep them viable by giving them good telehealth services, specialty support, radiology support," he said at the October event.

Sanford owns or manages dozens of hospitals and hundreds of clinics and long-term care centers, as well as a health insurance company. The system reported about $81 million in operating income during the first six months of fiscal year 2025, according to a recent bond rating report.

Last year, Sanford opened a "command center" for its systemwide telehealth initiative. It launched a telehealth expansion in 2021 and offers virtual care for 78 medical specialties, Sanford President and CEO Bill Gassen said.

"We've tried to imagine, what if that number doubles?" Gassen said. The startup costs for telehealth are high, he said, and the rural fund could be a unique opportunity "for us to make virtual care available to more patients, to more communities, to more hospitals and health systems across the country."

Gassen, who is set to chair the American Hospital Association in 2027, said Sanford leaders have met with state and federal officials, including Oz, whom he's known for years, and Chris Klomp, a top deputy at CMS and a senior adviser to Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

The word "telehealth" appears 36 times in the rural health program's 124-page application guidelines. But Don Robbins Jr., chief executive of a small hospital on the Illinois-Kentucky border, chuckled at the idea of using the funding for that purpose.

Robbins, whose 25-bed Massac Memorial Hospital averages five to seven patients in its beds each day, said his hospital does not regularly offer telehealth. Even if it did, he said, patients living more than a mile outside of town couldn't use it because they don't have a good internet connection.

The small hospital reported a $31,314 loss in September, Robbins said. "I think if we get anything out of it," Robbins said of the rural health program, "we'll be lucky."

Kopplin, the physician assistant who attended the South Dakota meeting, is cautiously optimistic about the rural health fund. She views it as a wonderful chance for states to test out ideas and learn from what works and what doesn't.

But "in a lot of ways this bill is going to be a band-aid approach" for rural health, she said. "It's not really going to fix the problem."

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the core operating programs at KFF — the independent source for health policy research, polling, and journalism.