BOLERO

★★★ ½

(PG) 121 minutes

Like most biopics these days, Anne Fontaine’s Bolero focuses on a particular period rather than trying to cram an eventful life into two hours. Although it frequently flips back and forth in time, leaving you trailing in its wake, its main interest is the tortuous lead-up to composer Maurice Ravel’s decision to settle on Bolero’s propulsive rhythm and repeat the same sequence seventeen times.

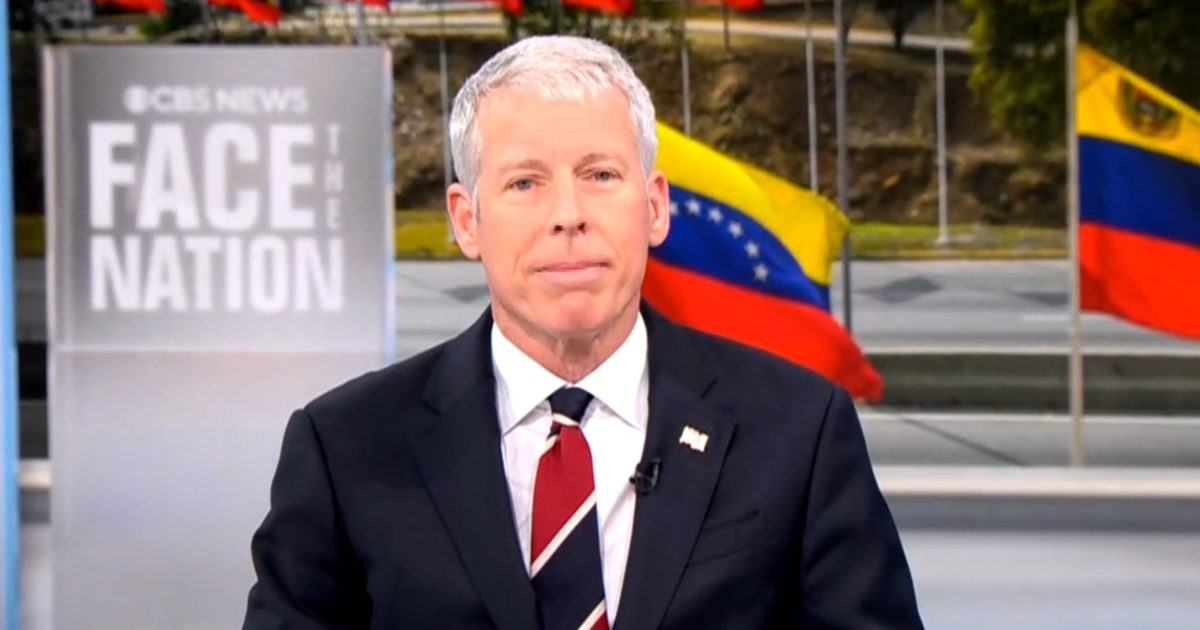

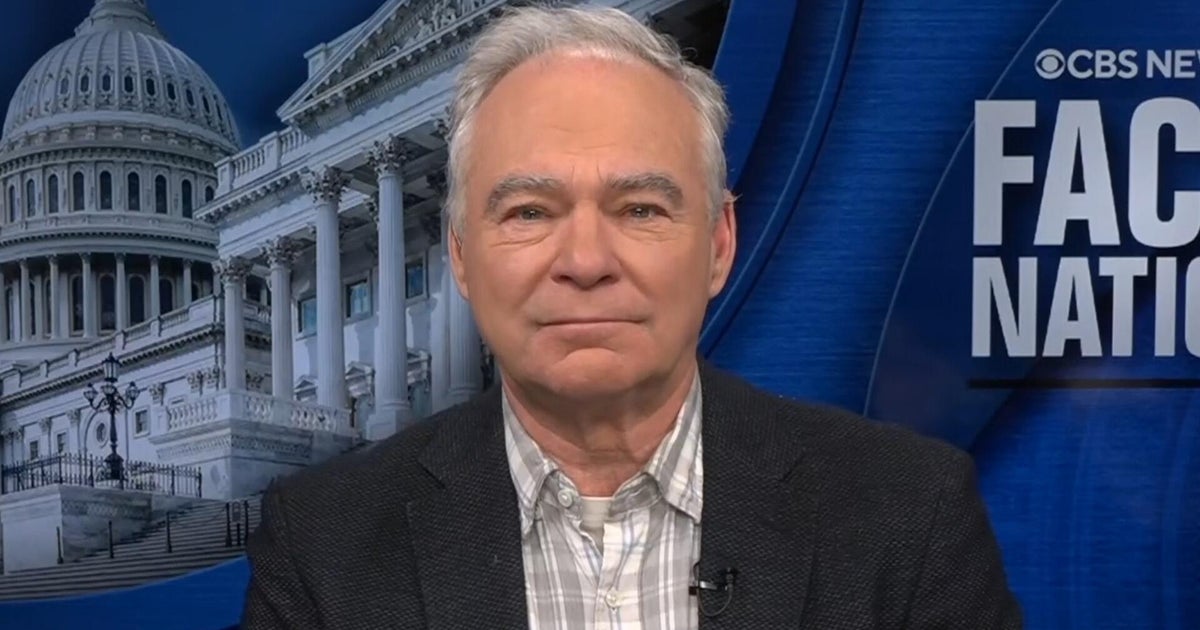

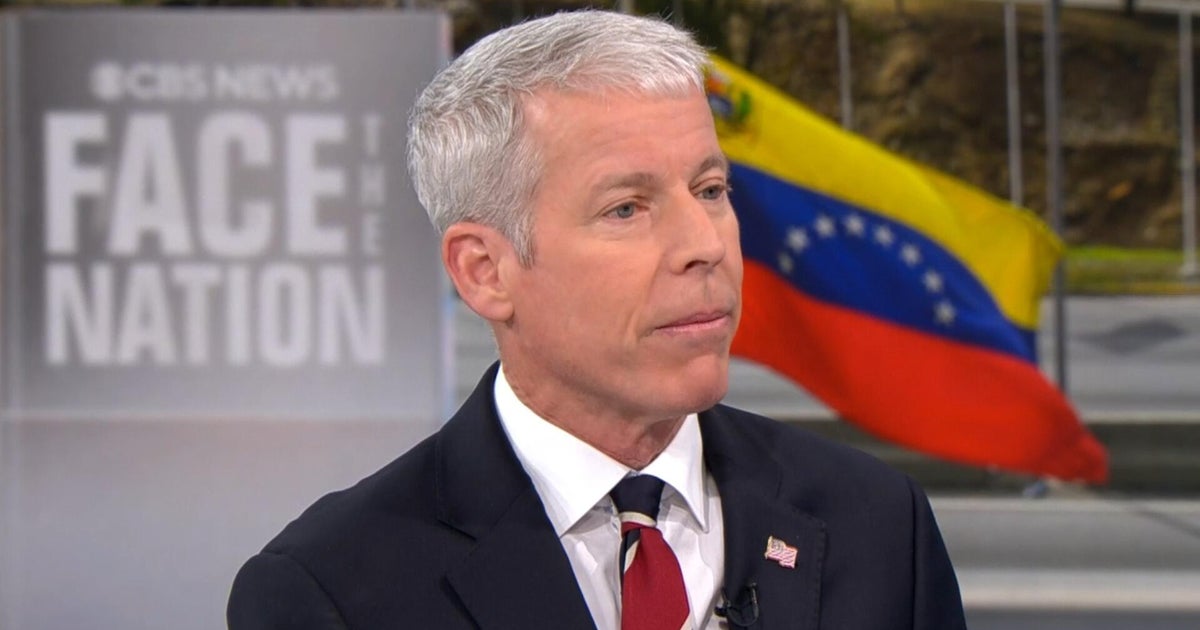

Raphaël Personnaz as Ravel in ‘Bolero’, with cast including Dora Tillier (Misia), Jeanne Balibar (Ida Rubinstein), and Emmanuelle Devos (Marguerite Long). Credit: Pascal Chantier

While much of his life was carried on in public, Ravel remains a mysterious figure. Fontaine’s research has led her to the conclusion that we can know him only through his music. A slight, boyish man with a handsome face and an air of remoteness, he had a close circle of women friends among the writers and artists of Bohemian Paris between the wars, yet he had no lovers and did not marry. Nor is there any evidence to back up the theory that he may have been homosexual. He is known to have gone to brothels, but Fontaine suggests that he charmed the girls he met there with music rather than sex.

The film begins in a factory. Ravel has the Russian dancer, Ida Rubinstein (Jeanne Balibar), meet him there to listen to the pounding cacophany which keep the place’s machinery going. And after she recovers from having to tramp through the mud to reach this sooty hellhole, she starts to understand what he’s saying. The ballet he is composing for her will be set in a factory.

This doesn’t come to pass. In the end, Ida, an Isadora Duncan-like performer, goes for a more erotic setting and Ravel is disgusted by her approach to the music. Nonetheless, the ballet makes him more famous than ever. Even the relentlessly vitriolic critic, Pierre Lalo (Alexander Tharand), is won over.

Ravel’s most loyal supporter is Misia Sert (Doria Tillier), musician, patron of the arts and spirited survivor of two bad marriages. But even she finds him impossible to understand. As she tells him wryly, she has no shortage of suitors and the only one who doesn’t try to seduce her is Ravel.

Fontaine gives us a gorgeously designed evocation of 1920s Paris, and she avoids the trap of having it turn into nothing more than a procession of famous names and faces like another recent French biopic, The Divine Sarah Bernhardt. And it probably sticks more closely to the truth, as far as the truth is known. But Ravel’s workaholic nature does dilute the drama.

Bolero is in cinemas from September 18.

Must-see movies, interviews and all the latest from the world of film delivered to your inbox. Sign up for our Screening Room newsletter.