Opinion

December 9, 2025 — 5.00am

December 9, 2025 — 5.00am

Deputy Prime Minister Richard Marles and Foreign Minister Penny Wong are visiting Washington this week for the 35th Australia-United States Ministerial Consultations, known as AUSMIN. This year’s AUSMIN will be markedly different to those of previous years. It is the first under the current Trump administration and comes amid a strategic environment that has shifted sharply in just 12 months.

Australia should use this AUSMIN to set clearer expectations with the US about our respective roles in an increasingly contested region and to advance the essential conversation on how responsibilities would be divided in the event of conflict.

The past three AUSMIN meetings have been successful, locking in expanded force posture initiatives and demonstrating a shared commitment to the rules-based order. Marles and Wong have been able to advance Australia’s interests while signalling alignment with the US on regional challenges.

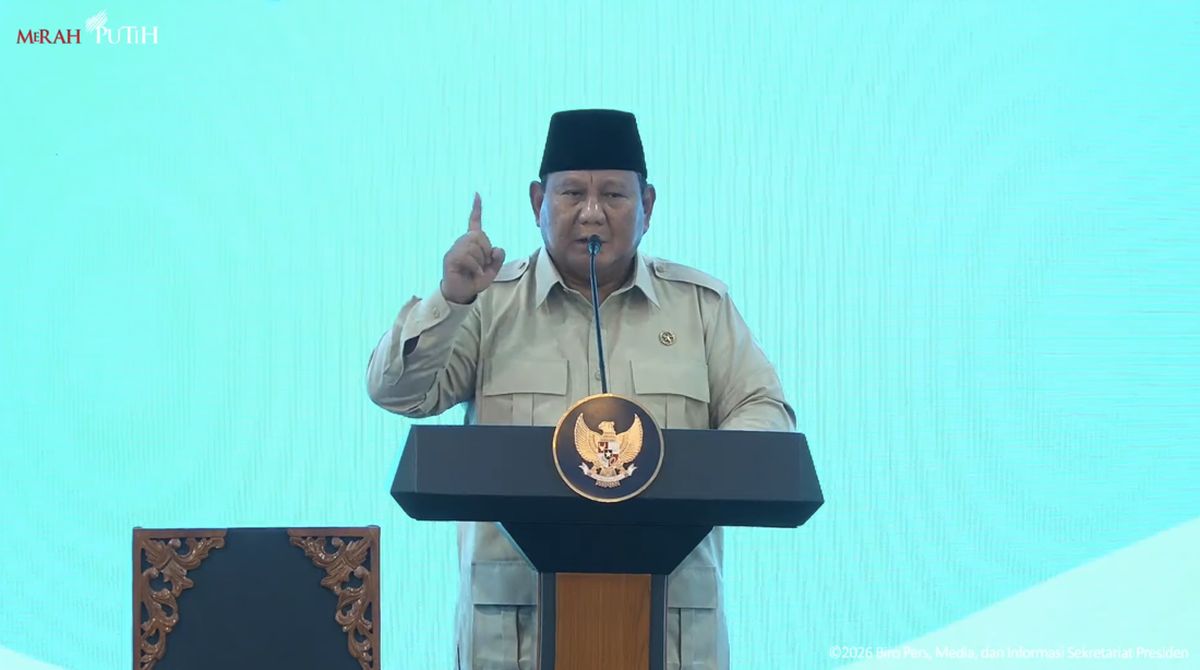

Richard Marles with US Vice President JD Vance and Secretary of War Pete Hegseth (right) in Washington in August.Credit: X

This AUSMIN is different. The US has deployed its largest force presence in the Caribbean in decades, raising questions about the legality of operations against drug-trafficking vessels and whether such actions comply with the law of armed conflict. That makes the usual language on upholding international norms harder to sustain. It also comes just days after the Trump administration released a new National Security Strategy that appears to view Australia differently.

Under the Biden administration, Australia appeared to hold a more prominent place in US thinking on the Indo-Pacific, reflected in repeated senior-level visits, AUKUS progress and expanded force posture arrangements. Yet in last week’s US National Security Strategy, Australia is mentioned only three times: once in reference to India and the Quad; again in a call for partners to adopt trade policies that “rebalance China’s economy”; and, oddly grouped with Taiwan, in a line stating that the US will maintain its “determined rhetoric on increased defence spending”.

Loading

None of this suggests the relationship is in poor shape. It is strong. The October meeting between Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and President Donald Trump was broadly successful, with Trump reaffirming his support for the alliance, praising Australia’s defence initiatives, including progress at the Henderson shipyard in Western Australia, and backing AUKUS “full steam ahead”.

Confidence has also been reinforced by reports that the US review of AUKUS has produced positive findings that endorse the pact and identify ways to strengthen it. What these developments signal is that the relationship must now be approached differently.

If the US National Security Strategy is any indication, at AUSMIN 2025 the US will place pressure on Australia’s defence spending and on what we are doing to strengthen our own capability. Marles will have several initiatives to point to, including last Friday’s announcement that Australia will begin manufacturing the guided multiple launch rocket system this month, a precision ground-launched rocket that can strike targets more than 70 kilometres away.

But we will need to do more, not because the US tells us to, but because more is required to defend our own national interests in an increasingly dangerous world. The modest increases already announced will take Australian spending from about 2 per cent of GDP to 2.3 per cent by 2033-34. These will cover nuclear-powered submarines and new frigates but little else.

The US is due to sell Australia at least three Virginia-class nuclear-powered submarines under the AUKUS agreement.Credit: Getty Images

Australia lacks many of the capabilities needed for modern conflict and to reduce our vulnerability to military coercion, at precisely the moment our strategic guidance warns that such a conflict is becoming more likely.

If the US National Security Strategy is any guide, Australia is also likely to face pressure over its trade dependence on China and aspects of that broader relationship.

The more important question for this AUSMIN is not where the US may apply pressure, but how Australia chooses to think about the relationship and what messages we want to send. Since the end of the Cold War, and almost certainly without intending to, Australia has become increasingly dependent on the US for security. Decades of constrained defence spending and limited strategic ambition reflect this trend.

The alliance remains vital, but in an unpredictable strategic environment, Australia must think carefully about how it protects its own autonomy while working with an ally that appears less driven by shared history and values than in the past.

Loading

As I wrote in this masthead in August, Australia needs a frank conversation with the US about roles and responsibilities, including the geographic delineation of missions in the region. I asked then who is responsible for defending Australia and its regional interests and noted that our strategy does not provide a clear answer. It should be Australia, supported by the US. That requires a direct conversation with Washington and a reassessment of our own strategy and force design.

AUSMIN 2025 is the moment to begin outlining those responsibilities. The Australia-US alliance remains central to our security, but the message from Washington is unmistakable. Australia will be expected to shoulder more of its own defence burden, and we should embrace that shift.

Meeting this moment requires more than higher spending. It demands clarity about the kind of relationship we want with the US and the confidence to define where Australia must lead. AUSMIN ’25 is the time to draw those lines and to shape an alliance that strengthens and complements, rather than substitutes for, Australia’s own strategic weight.

Jennifer Parker is a defence and national security expert associate at the ANU’s National Security College. She has served for more than 20 years as a warfare officer in the Royal Australian Navy.

Most Viewed in National

Loading