I have come to Roquebrune-Cap-Martin to see a house. When I say it in my head I roll the R’s extravagantly but when I say it aloud whoever I’m talking to says, “Where?” “The South of France,” I reply. “The Riviera. Near Monaco. Grace Kelly. Cannes. Le midi, mais oui?”

I left Paris at 6am and caught the train from Gare de Lyon. I had imagined an empty carriage, a forward-facing seat with a table, the French countryside unfurling outside my window. I would write for the whole five hours. But there are no tables and I am facing backwards. The man next to me is eating some kind of meaty sandwich, then shifting, sleeping, snoring. A woman keeps getting up to do pilates in the aisle with a resistance band. She’s wearing a floppy hat. She keeps it on the whole time.

When I made the booking I guessed the wrong side of the train, but after a mass exodus at Monaco I swap to the right for unadulterated views of craggy hills and the forever blue Mediterranean. The next 10 minutes make up for the last four hours. There is nothing like mountains and sea and sky.

And houses! Grand and humble houses on hillsides, wedding-cake white with red tiled rooftops and sea-slung patios and terraced gardens, they come at me faster than I can hold them in my mind’s eye. The house I have travelled to see, E-1027 (the name a code for its creator’s initials) is the modernist seaside villa of my dreams. Built between 1926 and ’29, it commands a corner of this dramatic coastline, but I don’t know exactly where. As the train approaches Roquebrune-Cap-Martin station, I get my first glimpse, and even though I am feeling tired and hungry and sweaty and ancient, excitement ripples through me. Soon I’ll get to see it up close.

Three weeks earlier, I was escaping Melbourne’s almost-winter at the movies. The film was E-1027: Eileen Gray and the House by the Sea (2024). I’d never heard of Eileen Gray – Irish, bisexual, furniture designer – or Jean Badovici – Romanian, architect, journalist, editor, social animal – and the house they built together. I didn’t know anything about the “feud” with Le Corbusier, or that in 1938, the big daddy of the International Style painted eight murals on the walls of Gray’s villa without her consent.

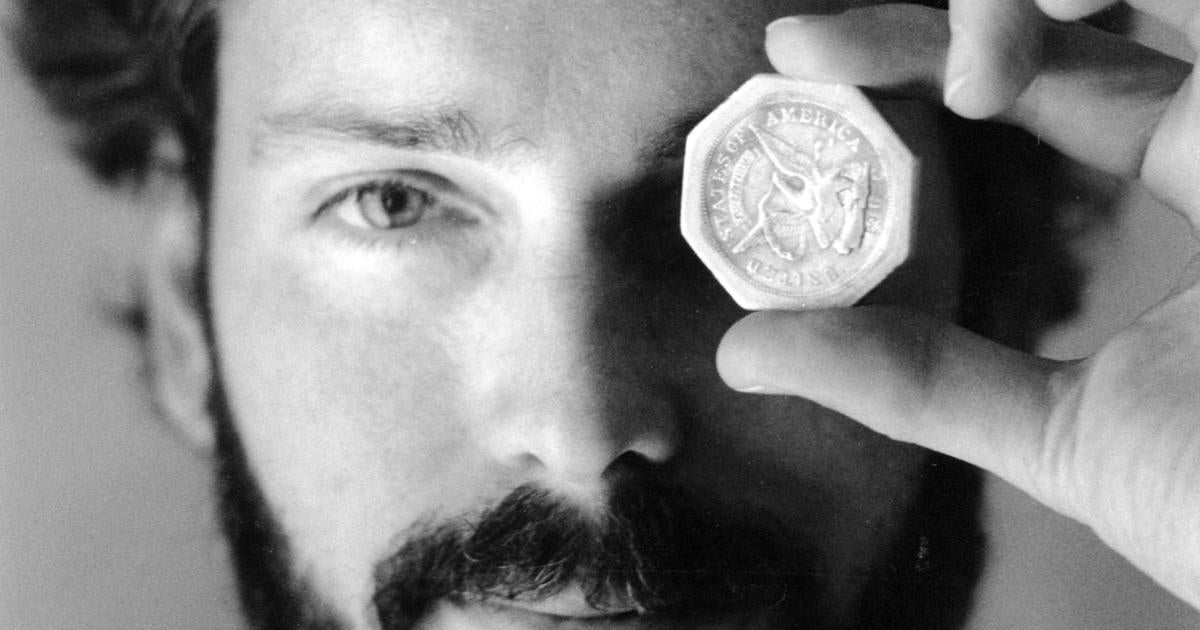

Architect Eileen Gray accused Le Corbusier of vandalism after he painted murals inside the house she designed.Credit: Getty Images

“This is a story of patriarchy,” director Beatrice Minger stated, “of a man who cancelled Eileen’s vision of architecture.” The murals were Cubist in style, vivid, lairy. In a photograph of Corbu painting them he is naked and not ashamed. Gray called it vandalism. Badovici liked the murals, initially. After he objected, Corbu sent him a bill for the paint. “Like all colonists, Le Corbusier does not think of it as an invasion but as a gift,” historian Beatriz Colomina wrote in 1993.

Le Corbusier would effectively spread himself all over the site at Roquebrune, building holiday shacks on the plot behind the villa and his monkish La Cabanon – “More a watchhouse than a cabin,” according to Colomina – directly next door.

For days after the movie, E-1027 was all I could think about. What if I could see it in real life? The more I thought, the bigger the dream billowed. Fortuitously, I was about to go to Paris. I pro-and-conned myself. I checked routes and accommodation. I worried about being a solo woman traveller – what about voleurs?

Loading

Then I calmed down, told myself it would be the French equivalent to getting the train to Albury-Wodonga. I bought a ticket for the English-speaking tour then I sat on it, because it seemed suddenly ridiculous to go all that way for a house. But – I don’t know – the jazz hands of fate were waving me forward. I got my debit card out, and ran riot.

The tour was led by a tanned young man. I got the sense he was Team Corbu. He told us that Gray and Badovici were not lovers and that it was hard to pinpoint how their collaboration worked. It was Badovici’s land but Gray’s design. It was Gray’s money but Badovici’s cheerleading. Gray camped onsite, tracing the sun’s path, copping the title “mad Englishwoman” from locals.

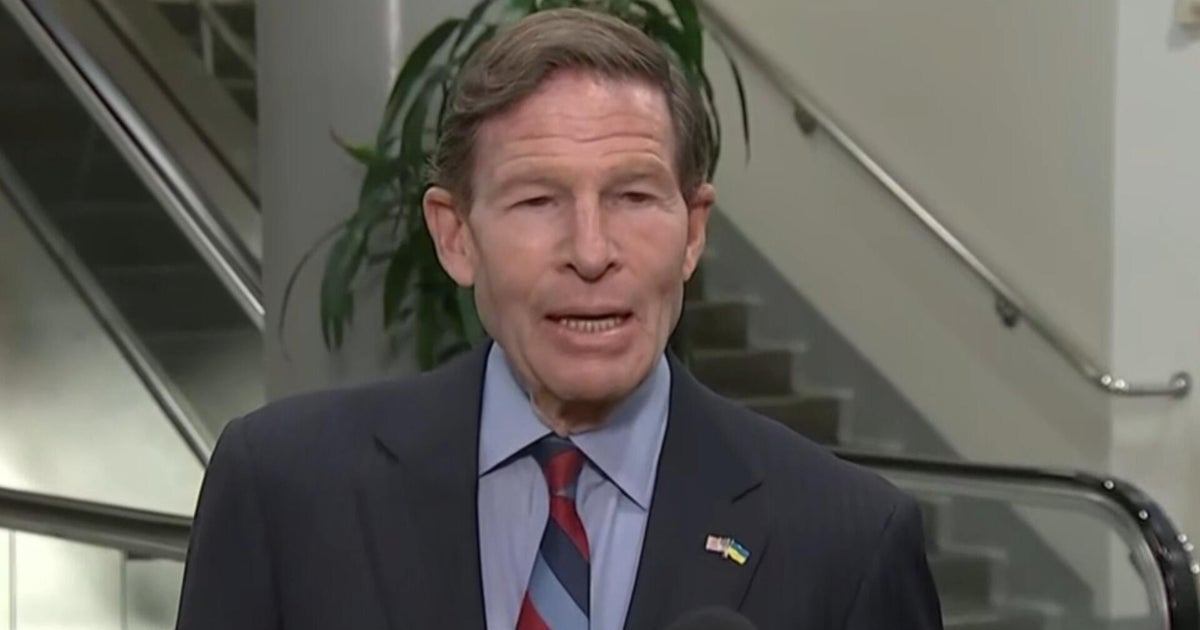

Architect and artist Le Corbusier “cancelled Eileen Gray’s vision of architecture”, says director Beatrice Minger.Credit: Wolfgang Kuhn/United Archives via Getty Images

Her design applied modernist techniques: pilotis, open plan, horizontal windows, and flat roof. Gray brought her experimental best to the project, furnishing the villa with a coffee table with adjustable height (no crumbs on the bed!), drawers that opened like Kali’s arms so the viewer could see all its contents at once, a cylindrical lemon server next to the bar, shutters on a sliding rail to manage privacy and ventilation. E-1027 was compact, complete as a shell: a synthesis of light, space and efficiency, fulfilling Gray’s stated aim: “House envisaged from a social point of view: minimum of space, maximum of comfort.”

Loading

“Entrez lentement” (enter slowly), the sign stencilled at the front door reads. There are similar signs throughout (citrons, oriellers, moustiquaire, papier a lettres). Our guide allowed that if you were a European modernist in possession of a villa, it was de rigeur to pass the key among friends. Although, he noted, Badovici was extra-friendly; he had an excess of joie de vivre and this was why he and Gray had parted company. It was also a class thing. Gray travelled with a maid. Badovici was “of the people”. Fortunately, Gray was adept at moving on. After a couple of summers she was ready to build a place of her own, on another hillside, somewhere she could be alone and work.

Dreamhouse as dreamspace: this is how it felt, even though I was there with strangers, being careful not to step on the rugs, under the eye of the house manager who waited wary on the balcony. I thought that if I had her job, or that of our droll docent then I could see E-1027 every day. I wondered if they lived locally, if it ever felt like a chore to repeat the same stories, and anticipate the same questions.

Despite its idyllic setting, E-1027’s history includes accusations of architectural vandalism, German occupation, and murder.Credit: Andia/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Loading

When the guide showed us through Le Cabanon, pointing out the toilet right next to where Madame Le Corbusier would have laid her head (Corbu slept on the floor) and someone joked about number twos, he tolerated it with good humour, but how many times had he heard it before? I never learned his name, the guide. Was he an architecture student? How did he get the job? Why didn’t I study architecture back when I was young and tanned and droll?

From the daybed in the main room when you look out the windows all you can see is sea. The effect is as if you are on an ocean liner. Gray had stencilled the title of Baudelaire’s poem “Invitation au voyage” in a mural on the wall. Architect Caroline Constant highlights the following lines as emblematic of Gray’s architectural achievement: “It is there we must go to breathe, to dream, and to prolong the hours in an infinity of sensations.”

But for all Gray’s care, once she had departed, bad luck dogged E-1027. In World War II the villa was occupied by German soldiers; Colomina writes of walls riddled with bulletholes. When Badovici died in 1958, the house went to his sister. Le Corbusier tried to buy it, but eventually it was sold to arts patron Marie-Louise Schelbert. After she died in 1980, her morphine-addicted physician, Peter Kägi, inherited it. He sold off much of Gray’s original furniture and the house became a setting for drug-fuelled orgies until Kägi was murdered there in 1996.

In 1999, E-1027 was bought by the Conservatoire du littora, which oversees the protection of significant coastal sites, but restoration was still two decades away. The villa and Le Corbusier’s Cabanon are now under the preserve of the Cap Moderne Association. The question of whether Le Corbusier’s murals should also have been restored (they were) is one that reverberates and hurts my head a little. Corbu, in his way, never left the site. He died of a heart attack while swimming in the sea out the front of the villa in 1965, and is buried in the cemetery in the hills behind.

At the end of the tour, some of the party talked about making a pilgrimage there, but I floated away, past the railway line down to la plage. I didn’t have a towel or bathers, but I had already decided I didn’t care. The stones on the beach were hell to walk on, but the water, once I made my way in, was heaven. I bobbed there awhile in my underwear looking up at Eileen Gray’s house by the sea. I thought of all she had seen – such a grande and storied dame! – and no voleurs took advantage, my phone and card stayed safe inside my cheap shoes on the shore.