Australian artist CJ Hendry built a cult following by establishing herself as a disruptor.

At first, it was rebelling against the “unattainable” art world with hyperrealistic drawings of plastic grocery bags and crumpled-up dollar bills. Then came the concept events, such as sending fans on a multi-city scavenger hunt for limited-edition wheelie bins.

But the South African-born, Brisbane-raised, New York-based renegade’s upcoming exhibition has some acolytes saying the revolutionary has finally gone too far.

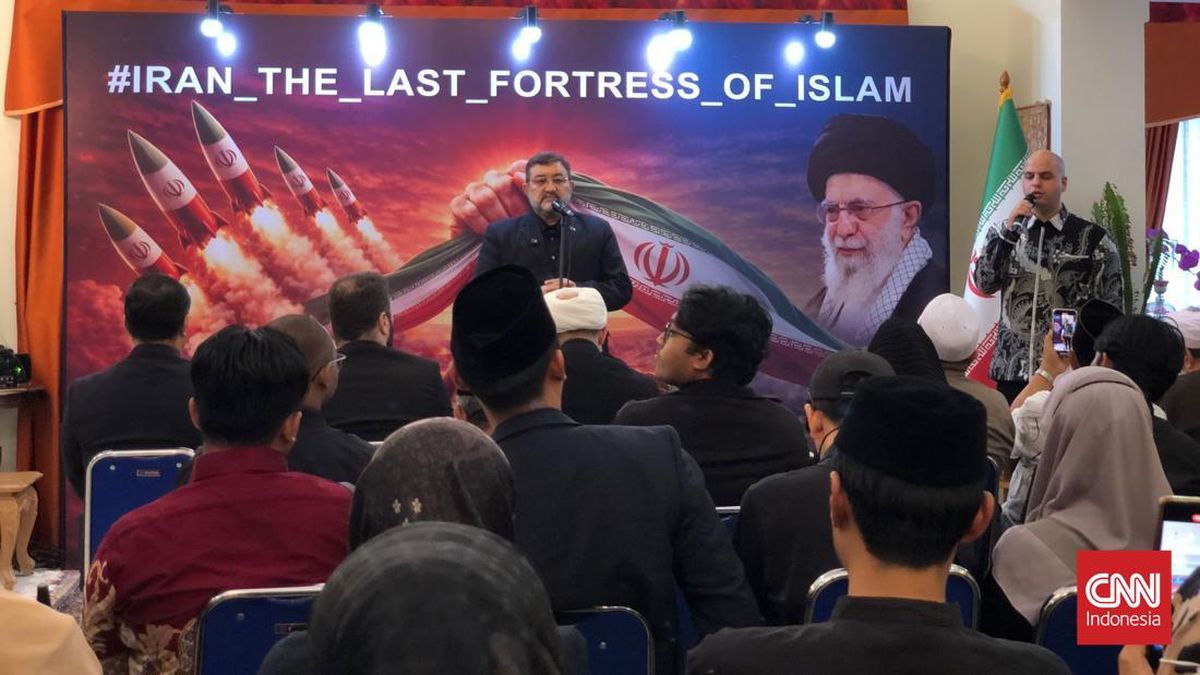

We asked a generative AI assistant to create an image for us that is a commentary on what art is, in the style of Andy Warhol. No further information was given, nor any reference images. What it spat out was this image of three metallic rabbits, similar to Jeff Koons’ Rabbit sculpture, which sold for $US91.1 million in 2019. It also misspelt “mass-produced”.Credit: Taylor Dent

From November 29, Hendry’s new exhibition of collectible art toys lands at Phillips Auction’s Hong Kong headquarters. The figurines are called JuJu and have already caused a stir. Why? Because the plushy toys with rabbit-like ears and Hendry’s signature flower motif over one eye were designed with the help of AI.

When a blind box turns into Pandora’s box

The project is a partnership with Phillips Auction and is a response to the Labubu craze. Tasked with putting a twist on the goblin-like figurine sold from $19 in a lottery-like blind box ritual that has collectors in a chokehold, Hendry – who has no prior experience with toy manufacturing but is no stranger to gamified exhibitions – turned to generative AI because “everyone seems to use” it.

In an Instagram story, Hendry showed her more than 920,000 followers how she entered reference images into ChatGPT, including one of a Labubu and another of Disney’s Mickey Mouse. Her text prompt noted: “They can’t be the same. They need to look unique in their own way.”

CJ Hendry has been transparent with her followers that the initial stage of her design process was done with the assistance of ChatGPT. The JuJu doll she said came out after prompt 37 appears almost identical to the eleventh doll that will be sold in blind boxes.Credit: Instagram/@cj_hendry/Aresna Villanueva

Over at least 37 subsequent prompts, the toys took shape. And Hendry was clear the pitch deck she presented to Phillips Auction – which also listed four one-of-a-kind 1.8-metre sculptures, each priced at $US200,000 ($A308,000) – was created with the assistance of ChatGPT.

Loading

The final designs, Hendry said, were finessed over a four-month-long exchange with her manufacturers, where they went through 35 “iterations and improvements”. But the eleventh doll in JuJu’s full line-up appears identical to what ChatGPT spat out after prompt 37.

The plush toys will be sold in blind boxes from $US24 ($36).

However, images created by AI are not considered copyrighted, unless the author significantly modifies it. When asked by a follower what significant modifications Hendry had made, she responded: “JuJu is for the people, I reckon.”

One fan wrote on Instagram: “You’re such a great artist. I’m so disappointed to see you’re using AI, the result is a subpar mishmash of things we already have.”

Can works created with AI be regarded as art at all?

Sydney-based Australian multidisciplinary artist Timothy Johnston views generative AI as an extension of human expression.

“The number of iterations that [Hendry] would have gone through, and prompts to learn … she’s such a perfectionist, she’s creating and creating, she’s like a potter with clay, she’s just not doing it by hand,” he says. “You still have to have the vision and put in the time to master the AI.”

As Hendry noted on a video posted to Instagram: “AI is like porn, it does a job, but it does not do the job!”

A representative for Hendry said the artist did not have time for an interview, a statement, or a response to this masthead’s emailed questions.

Live illustrator and art teacher Cat Long, who believes art generated wholly by AI – though she is not suggesting JuJu was – is, for now at least, very distinguishable from human creation. That’s why she says the two aren’t comparable.

‘AI is like porn, it does a job, but it does not do the job!’

CJ Hendry“Does AI take the soul out of art? Does it take the spark and creativity?” Long wonders. “Things created wholly by AI, there’s probably a place for them, absolutely, in the art world … But I don’t think that they’re competing with art that’s created for the soul.”

Not everyone agrees with that view.

What it means for the artists if AI is using existing art

Some commercial works are being created using already existing art and the artists are not being compensated.

“Creative work can now be produced by anyone without requiring the development of skills and expertise, but this is only made possible by existing creative work underpinning the process,” warned federal arts body Creative Australia in a June submission to the Productivity Commission.

“This work is often being used without consent or compensation, with significant potential impact on the financial viability of creative careers.”

Aboriginal artist Emma Hollingsworth, who sells art by the name Mulganai, says one of the reasons she wanted to bring her art to the world stage was so she could bring awareness to her people and her culture.Credit: Emma Hollingsworth/Mulganai

It’s an impact felt keenly by some First Nations creatives artists, who refer to AI models training with and reproducing their art without consent as “double colonisation”.

Kaanju, Kuku Ya’u and Girramay digital artist Emma Hollingsworth, also known as Mulganai, simply calls it “creative theft”.

Loading

“My art isn’t just a pretty picture, it comes from my identity as an Aboriginal woman,” says Hollingsworth. “It’s tied to my family, ancestors, Country and stories. AI has none of that: no lived experience, no cultural memory, no spirit or connection to Country. It can imitate styles, but it cannot carry our culture or our history.”

In September, Hollingsworth found multiple replicas of her art being sold on Temu for $5 (the listings have since been taken down). Her art is a part of her, Hollingsworth says, but it also “keeps a roof over my head”.

Contemporary artist Blak Douglas has also seen AI-generated images resembling his art floating around, but he’s not concerned.

Douglas, like Hendry, is a rebel – and his pop art-inspired portrait of Wiradjuri artist Karla Dickens won him the Archibald Prize in 2022. The Dunghutti man calls generative AI the “autotune of visual art”, and sees it as an opportunity “to reach the masses to tell them that Aboriginal art is different, modern, contemporary”.

Since he started painting 26 years ago, the Dunghutti man says, First Nations art has been governed by the dot paintings stereotype.

“It’s like this artistic analogy of keeping Aboriginal people within a mission,” says Douglas. “It would be nice if the layperson Googled Aboriginal art, they might see Blak Douglas.”

Archibald Prize-winning modern contemporary artist Blak Douglas sees potential in generative AI to challenge people’s perceptions about what Aboriginal art is.Credit: Louise Kennerley

Is it ‘autotune of visual art’ or something more sinister?

A through-line of Hendry’s body of work is that, like Andy Warhol and Douglas, it disrupts the status quo and challenges what art is.

Loading

JuJu, Hendry says in an Instagram Story, is a commentary on how “extraordinary and ridiculous” the Labubu craze is. But long-time Hendry fan Ruby PH, a Sydney-based designer who admires Hendry’s commercial success, doesn’t see it.

They say while it’s important to engage with AI and not turn away from conversations surrounding it, they were disappointed that Hendry implied other toy makers commonly used generative AI.

PH says, in their experience, people making toys have storytelling backgrounds, and develop 3D animation and illustration skills to bring their characters to life. Labubu, after all, was an original character created by artist Kasing Lung before Pop Mart made it a toy.

“If you were trying to make a statement about hyper-consumerism … why just do the exact thing that it’s doing? I don’t see the parody in that,” says PH, noting the final exhibit has yet to be unveiled.

Where to now?

Although Hendry has flirted with copyright infringement (she’s given T-shirts away for free to avoid being sued) since picking up a pencil, there is no suggestion of wrongdoing. Hendry has also been transparent about her use of generative AI, which is one of Creative Australia’s principles.

Sydney-based designer Ruby PH says they admire Hendry for her commercial success and talent, but are disappointed with Hendry’s use of generative AI in the initial stages of designing her JuJu exhibit.Credit: Janie Barrett

In October, a proposed amendment to Australian copyright laws, which would have given tech firms carte blanche to train AI models on the work of local creatives, was quashed after a successful campaign fronted by artists including singer-songwriter Jack River (Holly Rankin).

Loading

This means that AI developers must seek permission before using creative works to train their models. Some visual artists, including Stephen Cornwell, are not taking any chances, using tools such as WebGlaze or Nightshade to protect their works from being scraped.

Setting fair industry standards that protect creatives – such as the tech sector stepping up by remunerating, and seeking consent from, creatives to use their work – is critical to ensuring a future where both technology and culture can thrive, says Creative Australia’s head of public affairs, Nicola Grayson.

“Being able to use AI in a safe, ethical way is potentially quite exciting,” says Grayson. “If we can work with the tech industry to really produce some great solutions, then the future will look bright.”

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in Culture

Loading