In 1984, President Reagan commemorated the 40th anniversary of the invasion of Normandy, and paid tribute to the World War II soldiers known as "The Greatest Generation." "These are champions who helped free a continent," he said. "These are heroes who helped end a war."

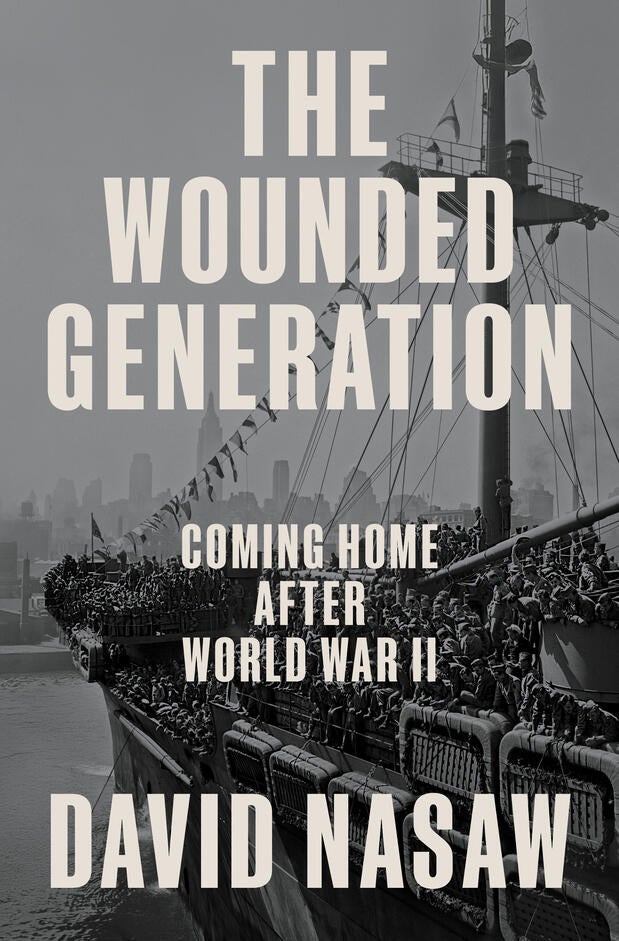

But in his new book, historian David Nasaw calls them "The Wounded Generation."

"They are the Greatest Generation, but they returned from war, bringing wounds home with them that are invisible; they're psychic wounds," he said. "Now we know that a lot of those wounds were PTSD. But PTSD was not diagnosed for 40 years after the return of the World War II veterans."

One clue he came upon was the famous photo of Times Square on VJ Day, 1945, of a sailor kissing a nurse. He's overpowered her; her fist is clenched. Nasaw saw something beyond end-of-the-war jubilation:

"Let's look very carefully: She's pulling away. He's grabbed her. He's locked her in. [In the second photograph], she's freed one arm, but he won't let go of her. Now, this is not joy. This is assault."

Photos taken in New York's Times Square on VJ Day, 1945.

CBS News

Photos taken in New York's Times Square on VJ Day, 1945.

CBS News

Nasaw said the woman spoke of the event years later: "She said, 'I thought I was gonna be suffocated. I didn't know who this was, where he had come from. He wouldn't let me go.'"

Nasaw saw something in the photo that touched a nerve. It reminded him of his own father, when he came home from the war after serving in Eritrea. "He came home an alcoholic," Nasaw said. "He came home smoking three or four packs of Luckys a day. He came home with a heart condition from the war. He dies at age 61. And I had never had the chance to find out what happened in Eritrea, what he went through. So, what do I do as a historian? I can't find out his story, so I jumped in to find out the story of his generation."

David Nasaw's father, Joshua, served in World War II, and came home a changed man.

CBS News

David Nasaw's father, Joshua, served in World War II, and came home a changed man.

CBS News

A Pulitzer Prize finalist for his biographies of Andrew Carnegie and Joseph P. Kennedy, Nasaw is a dogged researcher. He combed through newspapers, magazines, and government records, and went back through movies, like "The Best Years of Our Lives."

One thing he found was that government officials knew enough to warn wives that the soldiers returning home were not going to be the same men who left. "This was one of the things that I learned that just shocked me," said Nasaw. "The wives and the mothers and the girlfriends were told, 'We'll do as much as we can in the VA hospitals, but you've gotta cure this guy. You've got to live with his temper and his drinking and his foul mouth and his inability to take care of his kids. And if he can't readjust, it's your fault.'"

Nasaw also writes about lobotomies given to those deemed the worst cases. "The men who came back totally out of it, unable to connect to their wives, to their parents, ended up in VA hospitals. The VA hospitals tried forms of talk therapy." Those who didn't get better were given electro-shock treatment.

"The VA hospitals do their best, but they don't know how often they should be treated, [or] how long," Nasaw said. "Shock treatments do no good. And the next [step] is lobotomies."

The government tried to ease veterans' reentry back home, in part to protect the nation's economy. "Congress understood in every war we have rewarded our veterans – from the Revolutionary War onward – with land bounties, with old-age pensions. But more than that, we were going to return to Depression when the government stopped funding defense plants. And when these 16 million guys came back looking for jobs, a GI Bill is written to provide unemployment compensation for the vets when they get back. Why? To keep them off the job market for a year. Free tuition, whether you want to go to a vocational school or whether you wanna go to college or graduate school, is provided for the veterans. Because the sense is that it may take four or five years to reconvert from a war economy to a peace economy."

The government provided mortgage guarantees for veterans looking to buy homes. This encouraged real estate developers to build entire suburbs, like Levittown on New York's Long Island, and apartments like Stuyvesant Town in Manhattan. "They worked out a deal with Metropolitan Life Insurance to give them all sorts of tax breaks and build this extraordinary complex," Nasaw said.

By the end of 1955, the G.I. Bill and other veterans' war benefits totaled $24.5 billion (around $435 billion in today's dollars), almost double the cost of the Marshall Plan which rebuilt Western Europe.

Penguin Press

Penguin Press

Yet, not all veterans benefited. "If you were a Black veteran – North, South, East, and West – the banks were hesitant to give you a mortgage," Nasaw said. "Without a mortgage from a bank, you couldn't get a mortgage guarantee. So, what happens? This nation is transformed. There's a new middle class, it includes Jewish immigrants, Italian immigrants, Polish immigrants, working-class people. Black veterans are shut out."

Black veterans also experienced violence against them. "The South has learned that the only way to put down what they fear is going to be an attack on Jim Crow is to use violence," Nasaw said. "The Black veterans come home and, you know, one of the ironies here is that they can't afford to buy new clothes, so they wear their uniforms. And for White politicians and a lot of White Southerners, seeing a Black man in a uniform is a direct provocation."

At the National WWII Museum in New Orleans, we found Nasaw at an exhibit of Purple Hearts. "My father got a Purple Heart; I never saw it," he said. "I asked him over and over again, 'Where is your Purple Heart?' And he just sorta shrugged."

While Nasaw might never know why his father earned a Purple Heart, or where it went, his research has uncovered new insights into the experiences of all war veterans.

I said, "The Vietnam veterans, when they came home and had all their problems, they thought that they were weak, because they didn't know that that was also true of World War II."

"In Vietnam it was not considered by the majority of the population a 'good' war, or a war that Americans won," Nasaw said. "Therefore, the Vietnam veterans suffered. What I've discovered is, it doesn't matter. There's no magic wand that makes the war go away from people who've been in combat, who risked their lives, whether you're in World War II, in Vietnam, in Korea, in Afghanistan, in Iraq. It's very much the same."

READ AN EXCERPT: "The Wounded Generation" by David Nasaw

For more info:

- "The Wounded Generation: Coming Home After World War II" by David Nasaw (Penguin Press), in Hardcover, eBook and Audio formats, available via Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Bookshop.org

- David Nasaw, Distinguished Professor Emeritus, City University of New York Graduate Center

National WWII Museum, New Orleans

Story produced by Kay Lim. Editor: George Pozderec.

See also:

- A French village honors a U.S. soldier killed in WWII ("Sunday Morning")

- A Medal of Honor recipient's continued service ("Sunday Morning")

- His grandfather's war: David Eisenhower on the general and D-Day ("Sunday Morning")

- From 1964: "D-Day Plus 20 Years - Eisenhower Returns to Normandy"

- Honoring America's war dead far from home ("Sunday Morning")

- Honoring America's WWII "Ghost Army" ("Sunday Morning")