By 2021, their relationship had spiralled into violence, with friends witnessing Zayat’s physical abuse in public. In November 2022, they moved out of their shared home and Dokhotaru rented the Liverpool apartment she later died in.

Despite their separation, Zayat remained possessive of Dokhotatu, exploding into rage whenever he discovered she’d spoken to other men.

In early April 2023, the month before Dokhotaru was killed, their relationship was at rock bottom. They had broken up but continued communicating, expressing their love for each other despite Zayat’s escalating violence.

On April 11, Zayat found messages he did not like on her phone and physically attacked her.

These acts of controlling, monitoring and restricting another person’s freedom are common characteristics of coercive control, which was criminalised in NSW in July last year.

Loading

Coercive control is a pattern of behaviours used to manipulate, intimidate, isolate and control a partner and develop an uneven power dynamic.

The day after this attack, Zayat told Dokhotaru that he was “truly sorry”. One minute later, he minimised his abuse into general relationship issues, writing: “I’m sick of all this bullshit.”

In a heartbreaking response, Dokhotaru said their relationship was “like putting together broken glass” and Zayat had destroyed her.

“I know I’ve done my part of damage also but it’s incomparable to what you have done to me,” she wrote.

A 2024 federal government study on gender-based violence found that five per cent of Australians believed women who do not leave their abusive partners are partly responsible for violence continuing. Research shows this victim-blaming can cause women to wrongly believe they are partly responsible for the abuse.

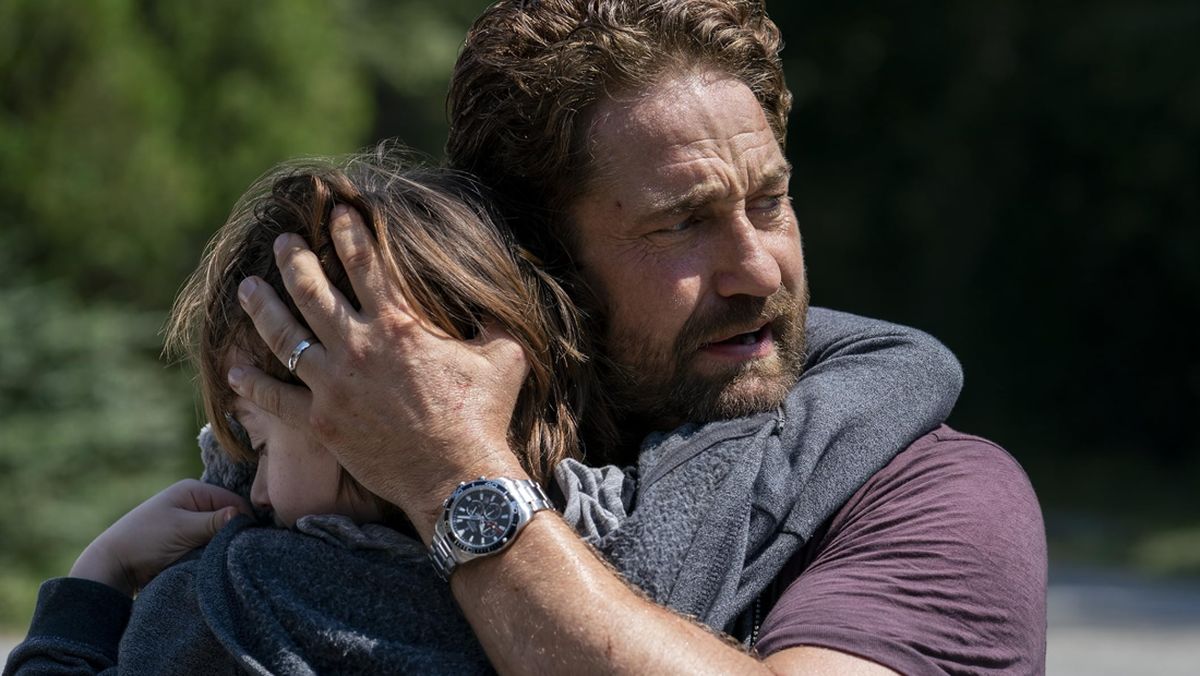

Tatiana Dokhotaru and Danny Zayat inside her apartment complex between seven and eight hours before Zayat murdered her.Credit: NSW Supreme Court

One text shows that Dokhotaru felt her capacity to love had somewhat “allowed” the abuse, which was caused by Zayat alone.

“I hate that my heart is so big and I love so deep. Look where it’s taken me,” she wrote.

Meanwhile, Zayat attempted to gaslight Dokhotaru, trying to convince her “fate” overrode his responsibility to be accountable for his actions. He wrote: “I can’t love anyone else the way I do you and I know you feel the same towards me despite what has happened.”

According to the Coercive Control Literature Review, published in 2023 by the Australian Institute of Family Services (AIFS), gaslighting is a common form of coercive control, which can erode a victim’s sense of self-trust and sense of reality.

When Dokhotaru asked for space to heal, Zayat agreed, but made her promise to “stay loyal” to him.

Four weeks before the murder

By April 29, Dokhotaru had forgiven Zayat. She shared her wish to reunite and move together to Dubai. Zayat wrote: “Yeah sounds good baby.”

Dokhotaru sent a photo of bundles of cash inside a shoebox, writing: “Let’s f---ing build an empire.”

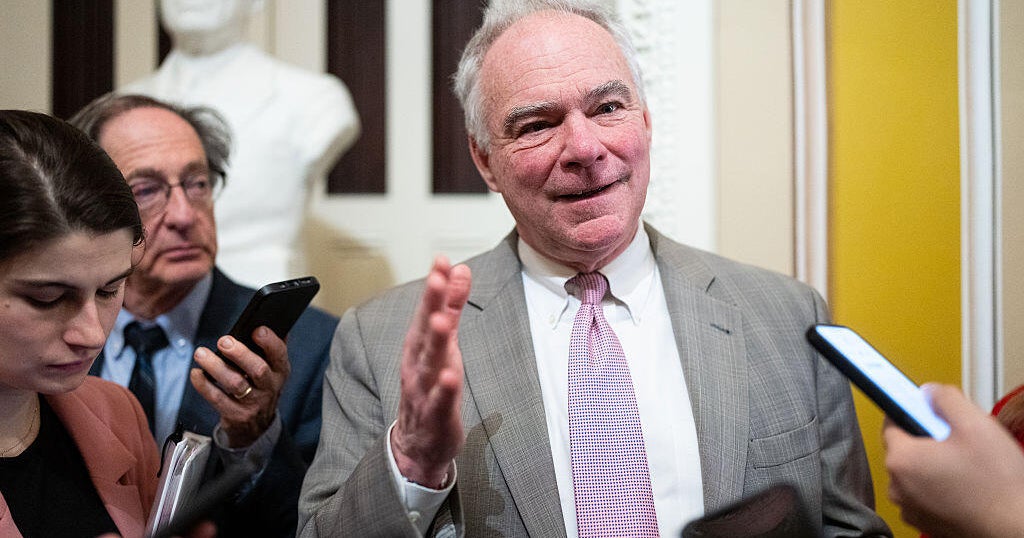

CCTV footage shows Danny Zayat leaving the Liverpool apartment minutes after committing murder.Credit: NSW Supreme Court

The Crown argued Zayat stole some of this cash from her unit on the night he murdered her.

Dokhotaru then wrote: “I love you … I’m giving you a second chance.” Zayat responded: “Trust me we are going to be better than ever.”

But, the next day, their dysfunctional relationship took another turn for the worse. Zayat again went through Dokhotaru’s phone and messaged a man on Instagram about photos she had liked. Then he brutally attacked her.

Dokhotaru sent him videos and photos of her bruises a day later, but he pretended they couldn’t load on his phone.

Two days later, Dokhotaru lent him money to cover overdue bills after a desperate plea, but asked him to pay her back “as fast as possible” because he’d previously taken “months and months” to repay her.

According to a study published by Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS), financial abuse is a common type of coercive control.

Two to three weeks before the murder

Research shows that psychological abuse also regularly accompanies physical abuse. This was another tactic Zayat used to shattered Dokhotaru’s self-worth.

On May 5, three weeks before her murder, Dokhotaru expressed sadness when Zayat told her “it will be better for everyone” if she died.

Then Zayat claimed he says things he doesn’t mean when he’s angry.

Zayat used derogatory language to try to control Dokhotaru’s social media use. Police warn this sort of technology-facilitated abuse is on the rise.Credit: Instagram

Laying false blame, he said it was “wrong” of him but was “nothing compared” to what she had done, and she didn’t have to “get over” his physical abuse “right away”.

One week later, after Dokhotaru left on a trip to Thailand, Zayat showered her with compliments and promised she’d “see a big difference” when she returned.

“I hope so,” she replied, adding she needed to learn to love herself as he’d made her hate herself. She’d become a shell of her former self.

One week before the murder

Zayat inflicted countless types of domestic abuse before he eventually murdered Dokhotaru, including secretly monitoring her phone and dictating her social media use.

Police recently warned that reports of technology-facilitated domestic violence in NSW had surged this year.

On May 17, while Dokhotaru was still in Thailand, Zayat used derogatory language instructing her to delete an Instagram photo. After some resistance, she did so, writing: “Fixed it.”

The next day, she said she wouldn’t “tolerate any mental or physical abuse … you still manage to mentally abuse me from a million miles away”.

Sketch of Danny Zayat as he was convicted in the NSW Supreme Court of murdering Tatiana Dokhotaru.Credit: Rocco Fazzari

Zayat said he “genuinely” cared about her and he “tries to make [her] feel better” when she’s upset.

After her return to Australia, Zayat learned Dokhotaru had spent a night with another man. He broke her ribs in a brutal bashing. Dokhotaru told friends she’d been in a car crash.

Three days later, on May 23, Zayat texted: “Hey babe how are you doing”, to which Dokhotaru said she was “so shit and depressed”.

Despite her pain being caused by his assault, a manipulative Zayat went into caretaker mode, telling her to “rest up” and she’d soon return to “normal”.

Night of the murder

As Dokhotaru grappled with the internal conflict of continuing to love Zayat but remaining trapped in his cycle of abuse, he slept at her apartment for the last few nights of her life.

On her last night alive, she shared a meal and some wine with a friend in her unit, before texting Zayat that her ribs were “about to pop” from his attack.

Minutes later, she said she missed him and was in “so much pain”.

“I miss you to [sic] baby, and I’m sorry,” Zayat responded, telling her he was heading over to her apartment.

At 9:50pm, he sent her his final text: “I’m here to look after you.”

Within two hours, she was dead.

If you or anyone you know needs support, the National Sexual Assault, Domestic and Family Violence Counselling Service on 1800RESPECT (1800 737 732).

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.