Geoffrey Watson had thought it was a “storm in a teacup”. When the corruption-busting barrister was first flown into Queensland by CFMEU administrators to look into the state branch’s use of violence after probes into organised crime infiltration of the Victorian arm, he’d done some prep.

“I’d read accounts of these things that were going on, and on paper, they looked so silly, so childish, schoolyard bullies, and I thought this is nothing,” he recounted this week. “It was then that I spent some weeks interviewing people when I realised I was wrong, and it was quite different.”

Those more than 55 interviews over three months, conducted with handwritten notes, would go on to form the June report that prompted the Crisafulli government to launch its powerful Commission of Inquiry into the CFMEU and Misconduct in the Construction Industry.

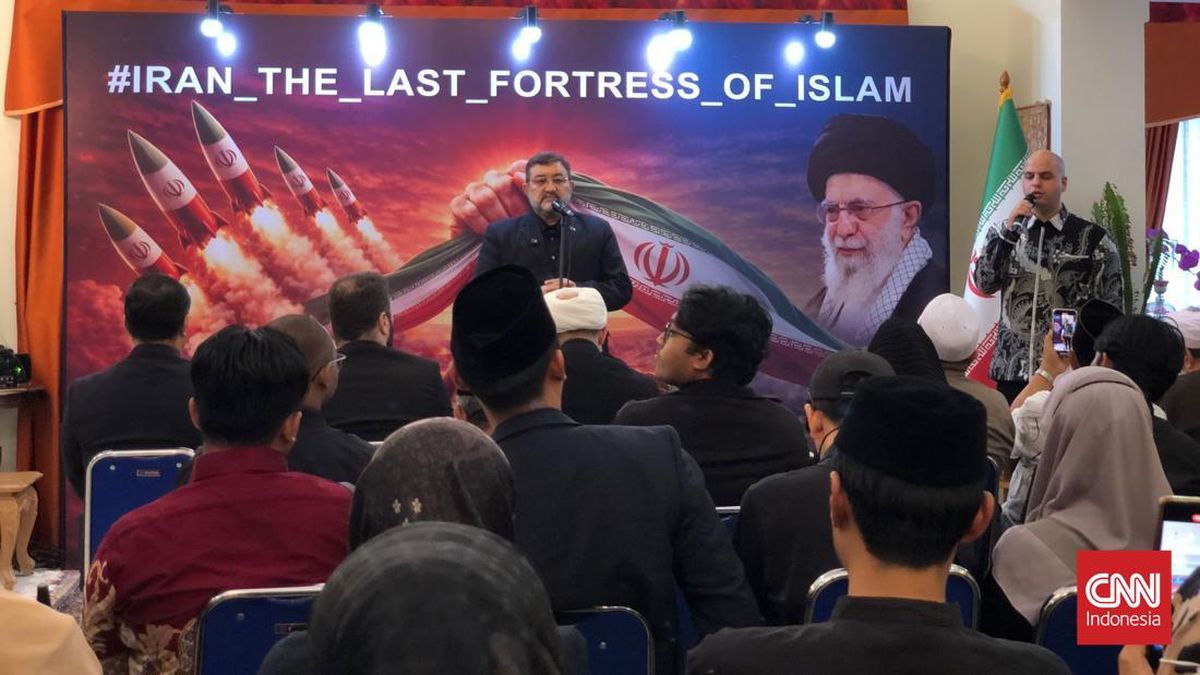

Geoffrey Watson gave evidence as a witness across the first two days of the inquiry this week.Credit: News Corp Australia

With still-lingering questions about the $20 million inquiry itself – including how it will play out, and how it will be used by a conservative government that has all but written off the union already – its first week of hearings has already pushed beyond Watson’s public work.

1. “Effectively, don’t squeal”

Among Watson’s day-one evidence was that he had heard ousted former assistant secretary Jade Ingham and his “stepbrother or a half brother”, Anthony Perrett – then still a union delegate – had transported fellow officials to their interviews with Watson.

While Watson did not use recording devices, he had invited anyone speaking with him to do so. On arrival for their interviews, the officials appeared with recorders – said to have been provided by Ingham or Perrett.

Mark Irving, KC, who was brought in to run the scandal-plagued union after it was placed into administration, confirmed this during his evidence on Thursday. Perrett drove some or many to the meetings with Watson, gave them the devices, and “no doubt provided those recordings to Mr Ingham”, he said. “Effectively, don’t squeal” was the message.

This and other insights gleaned through whistleblower provisions revealed “criminal offences having occurred and threats being made against various people”, Irving said, which led him to contact police.

Next, he called then-inquiry secretary Bob Gee and suggested he seek that information from police “because it may affect the operation of the commission of inquiry”.

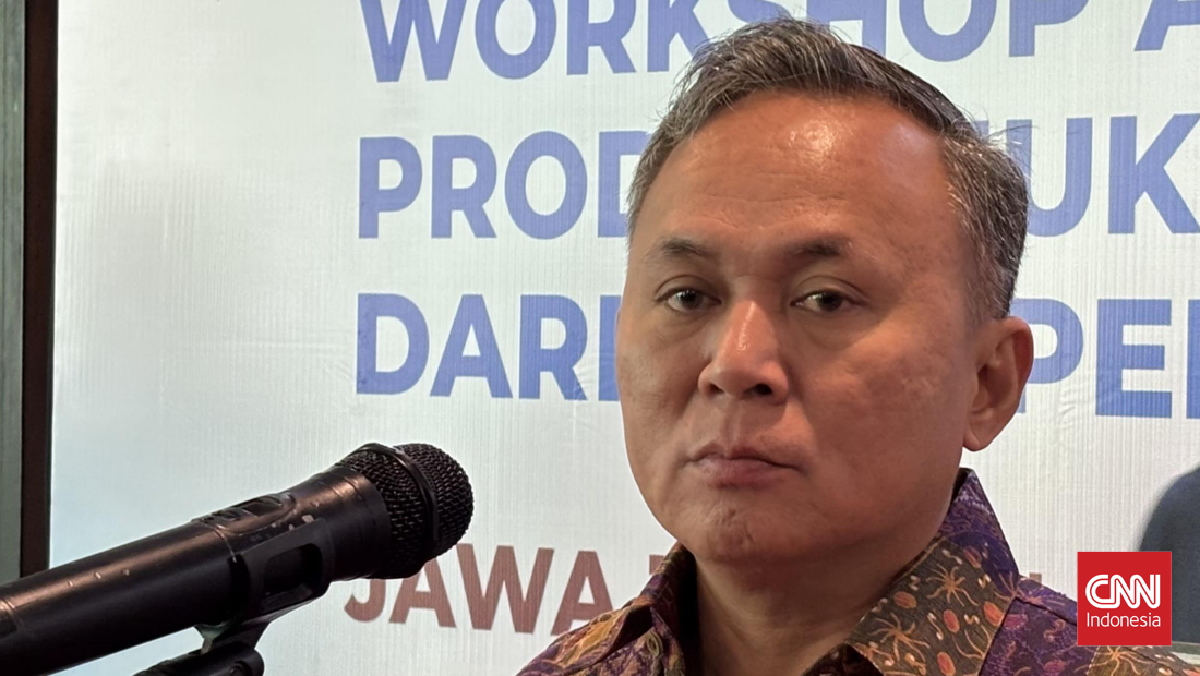

CFMEU administrator Mark Irving, KC, appears before the inquiry this week.Credit: News Corp Australia

Perrett was removed from his role in early August due to performance and construction site conduct concerns, with fellow unionists telling this masthead he was believed to have been among a clique of CFMEU operatives active in the push by Ingham to regain union control.

Detectives charged Perrett, 38, later that month over unrelated allegations that he was involved in the torture of missing man Andrew Burow. Additional charges of kidnapping, extortion, murder and interfering with a corpse were added last month.

2. The “service agreement”

The inquiry heard details of some of the Queensland union’s financial arrangements, as well as a “service agreement” between its two related entities: the Queensland and Northern Territory branch of the federally registered union, and a Queensland-registered union.

This agreement saw up to $50 million in fees from the state’s 15,000 to 20,000 members paid to the state-registered body instead of the federal one, stripping members of internal voting rights for elections, which had gone uncontested for 15 years.

Former Queensland state secretary Michael Ravbar speaks to protesters outside state parliament in February 2024.Credit: Matt Dennien

Irving said Ravbar and Ingham entered the agreement through their positions on both entities – without advising the national union governance body and without legal advice – in the days after the unopposed 2020 election of the pair and their “team”.

A range of investment properties then appeared to be acquired by the state-registered union.

Irving noted he sought legal advice to correct the arrangement, which he described as contrary to union rules and the law. There would also be a “vast amount of documentary evidence which will set this all out”.

Loading

“I have formed a view about the legality of those transactions, and that view will inform what actions I take against Mr Ravbar and Mr Ingham in terms of expulsion from membership, and in terms of any actions that need to be taken to report things to other authorities.”

3. Ousted leaders’ “shadow control” only ended mid-year

Irving also revealed the difficulty in prising “shadow control” of the branch, which he said was exerted until June or July this year, away from what he described as Ravbar and Ingham’s coercively controlled “fiefdom”.

It was only at this time, following Watson’s report into violence in the branch and the leaders’ unsuccessful High Court challenge of the administration, that he said he saw a chance to seize real control himself and determine the “good soldiers of bad generals”.

While Watson had told the inquiry he believed the situation in Queensland and NSW was “under control”, Irving said the fledgling nature of this meant his oversight was still needed – though the state branch was ready and willing to move forward with regulators, employers and governments.

4. Figures sacked, made redundant – and facing expulsion

The release of an unredacted version of Watson’s report, and a private one originally provided only to Irving, saw the identities of CFMEU figures involved in some of the incidents revealed – along with Watson’s assessment of their future in the union.

Additional evidence tendered by Irving confirmed all except delegate Rouel Harding and co-ordinator Dylan Howard had now been removed, had resigned, or took redundancies. Howard, Irving told the inquiry, had given a commitment to change, which he had accepted.

Irving also confirmed he had started disciplinary proceedings against Ravbar and Ingham, which could see the pair expelled from the union, and was considering such action for other national figures, including former Victorian leader John Setka, but against no others in Queensland.

Loading

Ravbar and Ingham, who refused to be interviewed by Watson based on what they later described as a lack of detail shared with them about the matters to be discussed, wholly rejected his eventual report and indicated through counsel this week they would defend themselves through the inquiry.

5. Little co-operation from big builders

Watson’s private report noted a number of potential witnesses were approached but declined to be interviewed.

While not identifying these beyond a still-redacted list, he wrote in the introduction he was “very disappointed” in the lack of co-operation from Cross River Rail contractor CPB and Centenary Bridge contractor BMD.

Loading

He separately told the inquiry of “very open” discussions with an industrial relations adviser on Cross River Rail who had been subjected to a “campaign” by the CFMEU before lawyers acting for CPB contacted him and “they all clammed up”.

6. The logistical hurdles ahead

The next three-day hearing is set to begin on December 2, with a witness list not yet prepared.

Beyond that, Commissioner Stuart Wood AM, KC, said he hoped to move hearings to an essentially full-time schedule from February until Easter, ahead of the (current) final report due date of July 31.

The only wrinkle? This week’s venue is only available for four weeks across the first half of 2026.

Other options, including “fitting out an office building as a courtroom”, were being considered.

“We just haven’t been able to determine the most cost-effective way of doing things,” Wood said.

Start the day with a summary of the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up for our Morning Edition newsletter.

Most Viewed in National

Loading