In a warehouse by the Bunnings in inner Sydney’s Alexandria, Mike Hewson’s studio is a Wonka factory of art. It’s an industrial space with skip bins four storeys high, a hoarder’s delight. Hewson, the Willy Wonka in my awkward metaphor, commands the place in a lime green jumper, pink floral shorts and work boots, the artist-tradie divide collapsed.

In an office upstairs sit his “soft sculptures”, salvaged construction bricks with googly eyes that he calls GeoPets, which he’ll sell by the pound at Sydney Contemporary. But the main floor is madness, carpenters and boilermakers at work on massive pieces that will make up The Key’s Under the Mat, Hewson’s transformation of The Tank at the Art Gallery of NSW into an “art park”.

In one corner’s a sauna, built into a 1980s ATCO hut – “the quintessential site shed,” says Hewson, like the ones he worked in as an engineer on construction sites in New Zealand, where he’s from (Hewson received a Bachelor of Engineering in Civil Engineering from Christchurch’s University of Canterbury in 2007). Inside the sauna, the temperature’s 70 degrees and it’s fitted with reclaimed pews from a church in Ryde; the shed’s graffiti-sprayed exterior – souvenirs of its found state – make the windows look like stained-glass. “I got all the sauna wood off Gumtree,” says Hewson of the western red cedar planks that line its interior. “I got all this stuff for four grand, but it’s probably about 40 grand worth of wood.”

Hewson outside his Alexandria studio, a hoarder’s delight.Credit: Steven Siewert

Next to the sauna is a working steam room that’s actually a disused milk vat he got from a dairy farm in Port Fairy, four hours south of Melbourne. Hewson pops the door and steam spills out, like an illusionist’s trick. “I was using it for a while at 5am every morning before work,” he says.

Opposite that there’s a barbeque, the kind you’d find at any roadside park, where Hewson expects families to grill their own sausage sizzles. “This will be whirring, removing smoke and odour,” he says, pointing to a grain bin-turned-exhaust hovering above on a forklift’s tines. “If you’re going to have a barbeque in an art gallery, you’d better be able to accommodate the smoke and odours so they don’t ruin the Picassos.”

There’s also a Hills Hoist on which hang four clothes dryers, a makeshift laundromat for attendees to wash-and-dry the “Nonna towels” provided for use in the water-play area that’s to be constructed from columns from the art gallery’s demolished northern tank that have been cored and turned into showers.

Out the back of the studio, labourers are working on an artist’s hovel that looks like something out of Wind in the Willows. In The Tank, it’ll be a workspace for the gallery’s artists-in-residence. “It’s a reference to the garden hermits of back in the day,” Hewson says, glinting with mischief. “Us artists often get relegated to the dregs; people bring us in for a bit of intrigue but they don’t really look after us. It’s the artist in the backyard who’s been given the hovel and allowed to tinker around.”

At The Tank, there will also be change rooms, an infinity loop of monkey bars, and a DJ booth for musicians to record and perform in. Hewson’s also building the floor – the carpark next to his studio is lined with cement pallets, some covered in hopscotch traces – to get running water and drainage into The Tank. It’s an insane attempt to bring the public park, or the traditional piazza, into an institution.

Skip bins, bricks and other salvaged materials line the walls of Hewson’s studio.Credit: Steven Siewert

It’s also a novel use of a space that, since its opening in December 2022, has leaned into its cold, moody history with exhibits by Adrian Villar Rojas and Louise Bourgeois. The Tank hasn’t typically been a place you’d want to be locked in after dark. With Hewson’s show, that might become every child’s (and inner child’s) dream.

“One of the great things about Mike’s work is that it throws into contrast all our assumptions about what an art museum should be,” says Justin Paton, head curator of international art at the Art Gallery of NSW. “You think of an art museum: white walls, silence, people usually walking around alone. You use your eyes, but you don’t use your other senses. There’s usually not anything to smell and you’re certainly not allowed to touch. Mike’s asking what would an art museum be like where you could gather together; where you could join friends to eat, talk and listen; where things that looked like artworks turned out to have unexpected uses?”

Floor plans highlight the madcap ambition of Hewson’s The Key’s Under the Mat show in the Tank at the AGNSW. Credit: Steven Siewert

Paton says it was experiencing Hewson’s Rocks on Wheels (2022), his divisive sculptural playground in Southbank in Melbourne, that spun him to the potential of Mike taking over The Tank. “It’s this amazing space with 300 tonnes of bluestone boulders that look like they’ve skateboarded into position. It looks like a risk manager’s worst nightmare, but turns out to be fully certified and is beloved by kids and adults.”

He invited Hewson to The Tank and found his instincts sharp. “He said, let’s light this space up like it’s two in the afternoon and let’s fill it up. Let’s create this underground art park, a kind of anarchic, sculptural neighbourhood,” says Paton. “Physically, it’s the most ambitious thing we’ve done in The Tank.”

Hewson’s interest in playgrounds began as an afterthought, while he was doing a public sculpture – Illawarra Placed Landscape (2018) – in Wollongong’s Crown Street Mall. “When Council renovated the mall, they removed the playground and didn’t replace it. Because there’s a methadone clinic in that strip mall, they had a lot of antisocial behaviour so they removed all the landscape architecture to clean it out, and it became like a tunnel so no one would gather. So I was like, maybe I can do a good thing and do a sculpture playground to put it back in for the public. It was as simple as, there was one there before and now there’s not, here’s an opportunity.”

It was a learning curve. His partner at the time’s daughter tried to climb the boulder and couldn’t. So he got practical, cutting holes here and there. “I quickly realised that it doesn’t matter how good the sculpture is – if the intended thing is for it to be a playground, who cares about your idea if it’s not useful?”

As much as salvaged and found materials, utility is key to Hewson’s work. He’s found it has a Trojan horse benefit when it comes to the bureaucracy of public art. “One of the big things I learned doing public sculptures is that the ones that were playgrounds received less public scrutiny because people have a big problem with waste of public money, so as soon as your artwork is actually doing something, it flies under the radar,” he says. “It might cost the same amount or be equally as snobby or alienating, but there’s something about the function that draws people in and disarms them. They go, ‘Well, at least my kid’s enjoying it.’”

In Sydney, he’s responsible for St Peters Fences (2020) in Simpson Park, which feels like playing in ancient ruins. He also refurbished the playground at Pioneers Memorial Park on Norton Street in Leichhardt, where brightly coloured buckets are stacked around giant boulders and fallen tree trunks. I was living next door to the park when it closed during COVID, I tell him, and when it reopened it was like, wow what happened here?

“Yeah, well, that was the public’s reaction, too,” Hewson deadpans. Due to their risk-positive philosophy, controversy has often followed Hewson’s works. It’s a major part of The Key’s Under the Mat, too.

Hewson started planning The Key’s Under the Mat two years ago. The gallery had approached him for a playground, but his vision expanded while he was at a pool party on a warm Sydney afternoon. A barbeque was happening, a friend was DJing, couples stood around holding hands, a kid did a bomb into the pool. “I was like, ‘That’s the show,’” says Hewson. “The idea was like, ‘Let the people live’, but it’s being embodied through materials and sculpture.”

As the pieces took shape, the ideas snowballed. “As soon as you have a sauna, it’s like, ok, you’re gonna need towels. And once you add towels, there’s nothing worse than laundry that smells, so I was like, we better do a laundry to clean them. So then you need hot water, and it’s like, ok, if we’ve got hot water, then we could have showers. So you come out of the sauna and have a shower, but then suddenly there’s all these man-bodies floating around. We don’t need it to be Ken’s house down there, so then you think we should have sauna clothes like a Korean bathhouse, so we’ve got these sauna shorts that we’re going to provide. Also you don’t want tinea, so we better provide sandals, too. Then when you come out of the showers, you’ll probably want to sit down and rest for a bit, so we better have seats because that’s one thing the gallery doesn’t have down there, is seats. So one thing leads to another until it’s like, ok, we’ll stop now,” Hewson laughs. “Allowing those things to meander and finding the logical conclusion so you can accommodate people is what’s most important. But the logistics of how that actually happens will be an interesting part.”

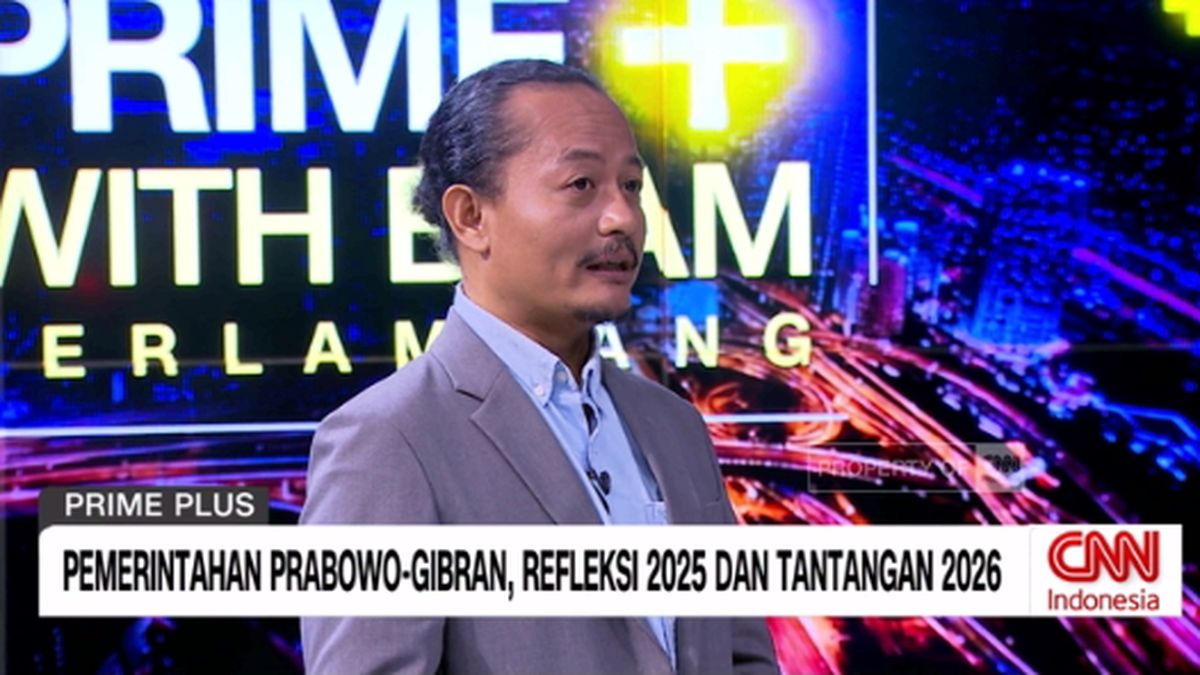

“It throws into contrast all our assumptions about what an art museum should be,” says Justin Paton, the AGNSW’s head curator of international art, of Hewson’s work.Credit: Steven Siewert

People are unpredictable, even more so when they’re being given free rein to behave in ways that are usually anathema to a gallery space. “I’m not arrogant enough to think I know how it’s gonna be,” says Hewson. “I’ve prepped the gallery from the start that there will be things we haven’t thought of, people’s behaviour might completely change, we don’t know if they’ll just start climbing up the columns.”

Still, he’s not keen on heavy invigilation. “A lot of these kinds of projects are impossible because the management costs get too high – paying salaries for people to have to tell you to get down off that and don’t touch this, for example. So the idea was, why don’t we just design it like a public park? The council doesn’t come down when you’re cooking on your barbeque and go, ‘What’s the date on those sausages?’ ” says Hewson. “All the projects I’ve done so far are in unsupervised 24-hour access spaces, so you have to anticipate 24 hours of good and bad activity in your space, and it’s the same for this. But if you make the artwork work hard for itself, it’ll look after itself.”

Paton is confident in Hewson’s vision. But the unpredictability is also part of the appeal. “As with Rocks on Wheels, what might at first appear to be perilous or difficult or improvised is all engineered to the nth degree. But this is a project that challenges the art museum to limber up and behave in different ways, to be a different kind of host.”

At a time when the Art Gallery of NSW is struggling financially to the point of job cuts and industrial action, The Key’s Under the Mat is a lifeline towards new audiences. “Absolutely, families and young people are at the heart of the art gallery’s vision,” says Paton. “We’ve all heard those depressing statistics about how long the average visitor spends with a given artwork – figures like three seconds per painting are often bandied around. But Mike is deeply committed to creating a space where people have a reason to stay and dwell and feel at home.”

Considering the type of work that’s traditionally been shown in The Tank, Hewson’s project – with its emphasis on function – has already ruffled art establishment feathers. But Paton says there’s a clear artistic lineage to Hewson’s work in playgrounds. In the show’s catalogue, he cites Palle Neilsen’s playground at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 1968 and the Group Ludic in France in the late ’60s and early ’70s, which designed public spaces with children’s input.

Complicating this is Hewson’s aversion to art-ish pretension.“I think pretension makes people blind to what’s around them. The materials of the world are so interesting and the life they’ve lived. Like, these bricks that we’re turning into little creatures for Sydney Contemporary, it’s sort of about observing the world and appreciating it. It’s not to say that my work can’t be snobby too, but I hope it’s like 10 per cent that.”

Hewson’s background in engineering drives his artworks and his use of recycled materials.Credit: Steven Siewert

During his time studying in New York (he received a Master of Fine Arts in Visual Arts from Columbia University in 2016), Hewson became interested in the bronze maquettes of the half-built playgrounds designed by artist and architect Isamu Noguchi near where he was living in Harlem. Rirkrit Tiravanija, who famously handed out Thai curry and rice at New York’s MOMA, was a classmate of Hewson’s at Columbia. If there’s a whiff of it in his sausage sizzle, that’s neither here nor there.

Loading

“No, I’m not trying to do clever art references,” says Hewson. His approach to his work is more practical, simpler. “I just go, ‘What’s here? What was here? What can we do with what we’ve got?’ The truth is people want to climb on things. And sculptures are particularly appealing to climb on. But you’re often not allowed to climb them. So why not just make sculptures and allow them to be climbed on?”

Mike Hewson’s The Key’s Under the Mat opens at the Art Gallery of NSW on October 4. He will be selling his GeoPets at Sydney Contemporary from September 11-14.