The Russians are exceedingly unhappy.

Australia has stolen back what the Russians planned was to be a distant corner of their motherland, carved out of prized territory near Lake Burley Griffin in Canberra.

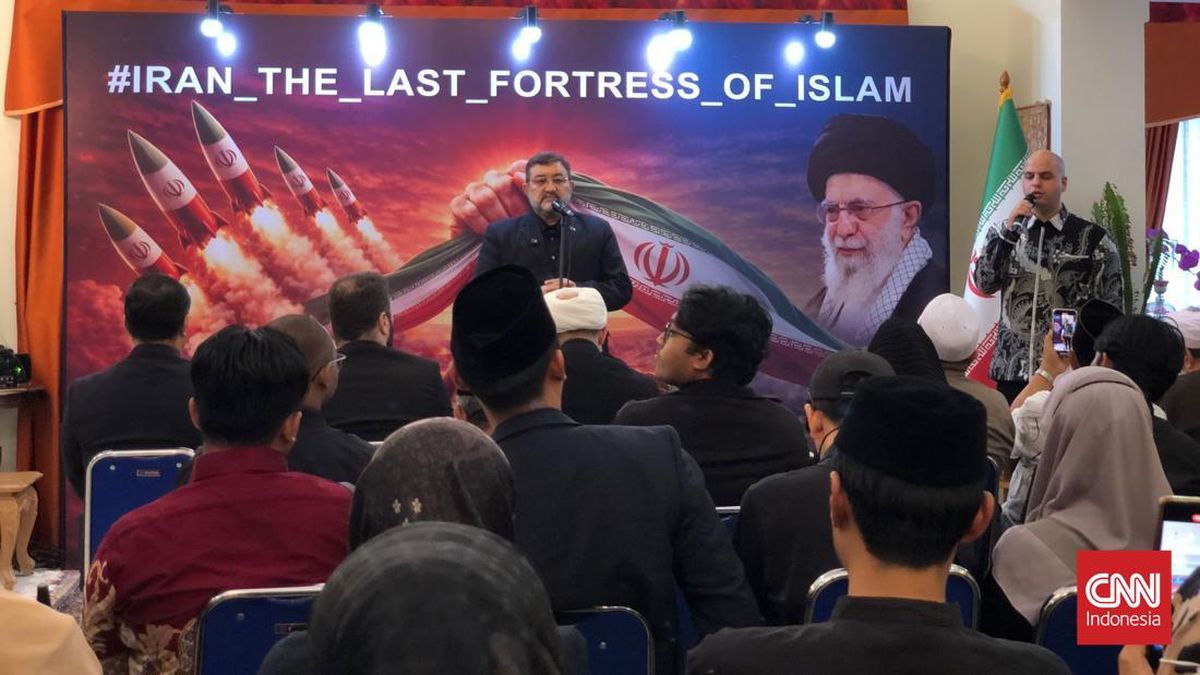

A small group of about pro-Putin protesters gathered outside the prime minister’s house at Kirribilli in June 2023 to demand he allow Russia to retain its proposed embassy site.Credit: Rhett Wyman

Furthermore, the Australian government retrieved the parcel of land legally, however much the Kremlin might call it a “hostile” action inflamed by “Russophobic hysteria”, a term used by Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov at the height of the long and peculiar stand-off.

Could it be that the Russians, whose president and military are trying with maximum prejudice to illegally steal a whole country known as Ukraine, have also misplaced the word “irony” from their language?

To explain. The High Court of Australia ruled this week that the Albanese government was within its legal rights when it revoked the lease on a prime block of Canberra land on which the Russian Federation wanted to build a new embassy.

Loading

The block, site of a post-Cold War saga stretching back 27 years, sits virtually across the road from Parliament House.

It would, once an embassy was built, effectively become Russian land under diplomatic protocol.

Far too close to Australia’s seat of power for comfort, so far as the nation’s security agencies were concerned.

Our spies fretted that it was a too-convenient spot for Russian spies – also known as diplomats – to aim high-tech surveillance equipment into the innards of parliament, where secrets are discussed and consigned to data banks and hard drives and whispered into classified ears.

If that sounded far-fetched, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese spelt it out when he first chose to face down the Russians, citing “national security concerns”.

He based this on what he said was “very specific advice from security agencies about the nature of the construction that’s proposed for this site, about the location of this site and about the capability that that would present in terms of potential interference with activity that occurs in this Parliament House”.

He didn’t add that the United States’ CIA wasn’t impressed with Russia’s plans, either, though he really didn’t need to.

The heavily guarded inhabitants of the giant US Embassy – itself across the road from Parliament House and just up the hill from the proposed Russian embassy – were not at all pleased, according to observers of the quiet world.

You need only survey the array of satellite dishes and other mysterious equipment on the roof of the US Embassy to know it has secrets it does not wish to share with neighbours.

Loading

Russia has long dreamed of quitting its drab old embassy down on the Canberra flatlands, far from the glamour of Canberra’s diplomatic belt, where it sits on a busy road opposite a pub and a funeral home.

For years, ASIO agents occupied a room above the funeral home, aiming their cameras at what was then the Soviet Embassy, recording everyone who entered or left the place. ASIO bugged the forbidding-looking embassy, too, but its agents were said to have never heard a word because the Russians were wise to the ploy. Now Australia’s authorities are less subtle, with a mobile video camera rig and police car more or less permanently stationed outside.

In 2008, when relations were less frosty, Russia took out a lease on a block of land amid the more glamorous embassies in the suburb of Yarralumla.

For years, no building took place. Eventually, the National Capital Authority, sick of waiting, took legal action to end the lease.

Russian officials protested loudly, claiming they had struck problems with a building contractor and the COVID period. The Russians went to court and won the right to retain their lease.

But then the Albanese government passed legislation revoking the Russians’ hold on the land altogether.

A Russian diplomat who had been staying at a shed on the site of a proposed Russian Embassy in Canberra leaves in June 2023.Credit: Nine News

Amid more outrage from the Kremlin, a Russian embassy staffer occupied the single shed on the site, apparently in the belief that a successful sit-in would take care of nine-tenths of the law.

Eventually, the whole strange business ended up in the High Court, where Russia’s lawyers argued that the Australian government’s legislation was unconstitutional.

This week, the High Court ruled nyet to the Russians’ objections.

The court, however, made clear Russia was due unspecified compensation for the loss of what it had considered its land.

Which, we might reflect, the citizens of Ukraine could only dream about.

Cut through the noise of federal politics with news, views and expert analysis. Subscribers can sign up to our weekly Inside Politics newsletter.

Most Viewed in Politics

Loading