Suhnwook Lee

BBC Korean

Reporting fromSeoul

Watch: 1979 news report on the assassination of President Park Chung-hee

Two gunshots.

That is how Yoo Seok-sul begins recounting the night of Friday, 26 October, 1979.

A former security guard in the Korea Central Intelligence Agency, or KCIA, as the South's spy division was known, Yoo has many stories to tell. But this is perhaps the most infamous.

He remembers the time - nearly 19:40 - and where he had been sitting - in the break room. He was resting after his shift guarding the entrance to the low-rise compound where President Park Chung-hee entertained his most trusted lieutenants. They called it the "safe house".

In his 70s now, wiry with sharp eyes, Yoo speaks hesitantly at first - but it comes back to him quickly. After the first shots, more gunfire followed, he says. The guards were on high alert but they waited outside for orders. The president's security detail was inside, along with the KCIA's top agents.

Then Yoo's boss, a KCIA officer who oversaw security for the safe house, stepped outside. "He came over and asked me to bury something in the garden." It was two guns, bullets and a pair of shoes. Flustered, Yoo followed orders, he says.

He did not know who had been shot, and he didn't ask.

"I never imagined that it was the president."

National Archives of Korea

National Archives of Korea

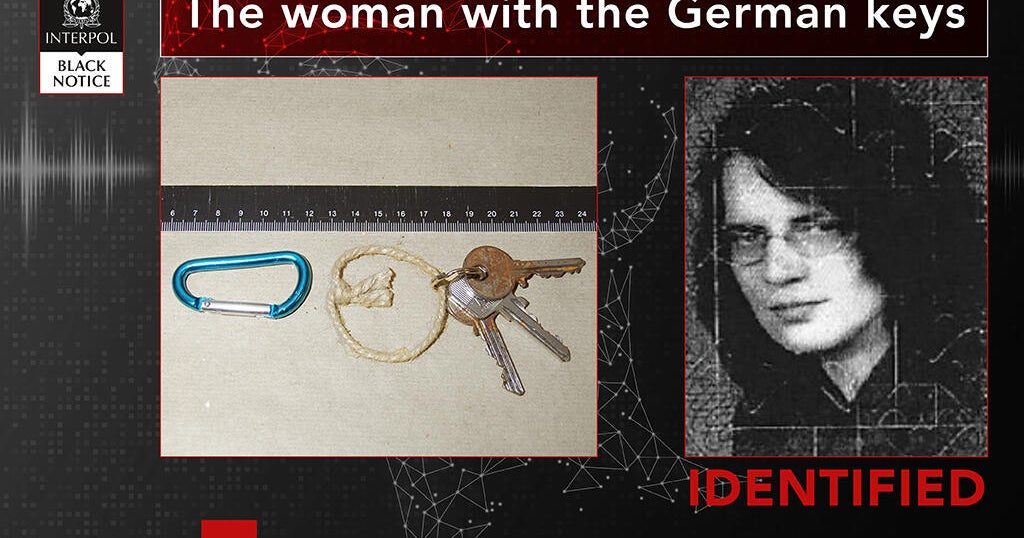

Kim Jae-kyu in military court during the trial in 1979

The guns Yoo buried were used to assassinate Park Chung-hee, who had ruled South Korea for the previous 18 years, longer than any president before or since. The man who shot him was his long-time friend Kim Jae-gyu, who ran the much-feared KCIA, a pillar of Park's dictatorship.

That Friday shook South Korea, ending Park Chung-hee's stifling rule and ushering in another decade under the military. Kim was executed for insurrection, along with five others.

Now, 46 years later, that night is back in the spotlight as a court retries Kim Jae-gyu to determine if his actions amounted to treason. He has remained a deeply polarising figure - some see him as a killer blinded by power and ambition, others as a patriot who sacrificed himself to set South Korea on the path to democracy. The president he killed is no less divisive, lauded for his country's economic rise and reviled for his authoritarian rule.

Kim's family fought for the retrial, arguing that he cannot be remembered as a traitor. They will now have their day in the Seoul High Court just as impeached president Yoon Suk Yeol goes on trial for the same charge that sent Kim to the gallows.

Yoon's martial law order last December was short-lived but it threw up questions about South Korean democracy - and that may influence how the country sees a man who shot dead a dictator he claimed was on the brink of unleashing carnage.

Was Kim trying to seize power for himself or to spark a revolution, as he claimed in court?

Getty Images

Getty Images

Park Chung-hee ruled South Korea for 18 years

When news of the shooting broke in the morning, it sent shockwaves through South Korea. Initial reports called it "accidental".

What was left of Park's coterie tried to make sense of what had happened. Kim had been a close ally since Park seized power in a coup in 1961. They shared a hometown and had started out together at the military academy.

Veteran journalist Cho Gab-je acknowledges that Kim seemed uncomfortable with some of Park's actions, but "there's no record that Kim actually acted on those concerns, no evidence he released political prisoners, clashed with Park, or submitted formal objections".

Kim told the court he had thought about killing Park at least three times. But history shows he supported Park as he tightened his grip, abolishing direct presidential elections and term limits, allowing him to control the National Assembly and even suspend constitutional rights.

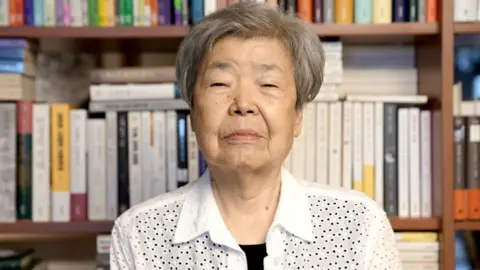

"My brother was never the kind of person who would commit such an act just to become president," insists his sister Kim Jung-sook, who is now 86.

But he ran the KCIA, which was notorious for jailing, torturing and even framing innocent students, dissidents and opposition figures with false charges.

"They tortured people, fabricated charges, and imprisoned them… and if you criticised that, you'd get arrested too," says Father Ham Se-woong, who was imprisoned twice in the 1970s for criticising the government.

Kim was not a saviour many could accept. But that is the mantle he took on, according to court transcripts that were not widely reported at the time. He told the judges he believed it was imperative to stop Park, whose ruthlessness could plunge South Korea into chaos and cost them a critical ally, the United States.

"I do not wish to beg for my life, as I have found a cause to die for," he said, although he asked the court to spare his men who followed his orders - "innocent sheep", he called them. He said he had hoped to pave the way for a peaceful transition of power, which had eluded his country so far.

On hearing about this back then, even a fierce critic like Father Ham tried launching a campaign for him. "He wanted to prevent further bloodshed. That's why we had to save him," he says.

Father Ham ended up in prison again for his efforts, as the trial became a sensitive subject. The country was under martial law. Days after the trial started - on December 12 - the man who led the investigation into the assassination, General Chun Doo-hwan, seized power in a coup.

Suhnwook Lee/ BBC News

Suhnwook Lee/ BBC News

Kim Jung-sook has been fighting for years for a retrial of her brother's case

Proceedings in the military court moved at lightning speed. On 20 December, it convicted Kim of trying to seize power through murder, and six others of aiding him. Yoo was sentenced to three years in prison for hiding the guns.

By 20 May the following year, Kim had lost his final appeal. Four days later he was hanged, along with three others. One was spared and another had been executed earlier. Kim died as the army brutally suppressed a pro-democracy uprising, killing 166 civilians in the city of Gwangju.

"I got the impression that Chun Doo-hwan was trying to quickly wrap up anything related to the previous regime in order to seize power for himself," says Kim Jung-sook.

She says she saw her brother just once through all this, a week before he was executed: "I think he sensed it might be the last time. So he bowed deeply to my mother as a goodbye."

Yoo survived but he says after he was free, he was followed for years: "I couldn't get a job. Even when I returned to my hometown, they kept tailing me. I couldn't say a word about the case." He now works as an attendant in a private parking lot outside Seoul.

Ms Kim says her family did not speak up until about 10 years ago. After South Korea became a democracy, Park's image recovered, improved by time and wealth. His daughter became president, often defending his legacy for its economic record.

It was her downfall - following massive protests over a corruption scandal - that threw open the door to revisit Kim Jae-gyu's conviction.

National Archives of Korea

National Archives of Korea

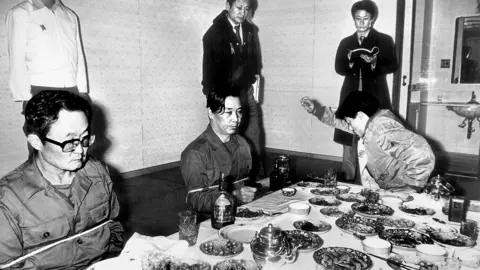

Kim Jae-gyu (L) and Park Chung-hee were close friends

"This case should never have gone to a military court because the assassination happened before martial law was declared," says Lee Sang-hee, the lawyer in charge of his retrial. She adds that the "sloppy transcripts" would have influenced his appeal because the defence was not allowed to record the proceedings.

"When I reviewed the documents, I couldn't understand how he could be convicted of insurrection when there was such little evidence. And above all, there was torture," she says, which the court cited as a valid reason when it agreed in February to a retrial.

It accepted Kim's statement, which he submitted in his unsuccessful appeal in 1980, alleging "the investigators beat me indiscriminately and used electric torture by wrapping an EE8 phone line around my fingers".

Reports at the time alleged that Kim Jae-gyu's wife had been detained and tortured too, along with her brother-in-law and brothers, which officials at the time denied.

Now in her 90s, his wife has always been opposed to a retrial.

"She never talked about what she had gone through and trembles even now," Kim Jung-sook, the spy chief's sister, says.

Ms Kim is resolute in her defence of her brother, repeatedly emphasising that "he was a man of integrity".

"Because we believe that he did not kill the president and his security chief for personal gain, we have been able to endure all of this."

Kim family

Kim family

Kim Jae-gyu is the first man standing from the left in this old family photo

The security chief was Cha Ji-cheol, who had been growing closer to Park, and often clashed with Kim as the two men vied for the president's ear.

In the weeks before the assassination, they differed on how to deal with Kim Young-sam, an outspoken opposition leader who Park saw as a threat. In an interview with the New York Times, the opposition leader had called on the US to end Park's dictatorship. The National Assembly, controlled by Park, expelled him.

The decision kicked off huge protests in Kim Young-Sam's strongholds. Cha wanted to crush the uprising, while Kim Jae-gyu advised caution, which would also reassure a Washington that was growing impatient with Park's rule.

Kim told the court he warned against firing at protesters, which would only ignite anger - to which Cha said, "three million died in Cambodia, and nothing happened. If we kill one million demonstrators, we'll be fine".

That evening at the safe house, the public broadcaster reported that the US ambassador was going to meet Kim Young-sam.

An angry Park criticised Kim Jae-gyu for not arresting the opposition leader. When Kim pushed back, the court heard, Park retorted: "The agency should be feared, it should prosecute those who deserve it."

Alamy

Alamy

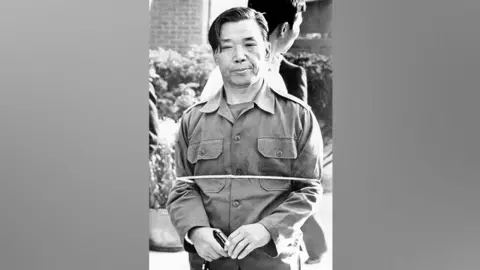

Kim holding a gun as he re-enacts the scene of the shooting, while investigating officers watch

They sat across from each other, sipping Scotch and sharing a meal. Park sat between two women, a popular singer and a young model. Cha and Park's chief of staff were also there.

The terse exchanges continued, and mid-way through a love song, Kim Jae-gyu said, he pulled out the gun, aimed it at Park and told him he needed to change his politics: "Sir, you should approach things with a more magnanimous vision - so this is not just about you."

Turning to a shocked Cha, he cursed as he pulled the trigger, wounding him in the hand as Cha tried to block the shot. Then Kim fired into Park's chest. Outside, acting on his orders, KCIA agents shot dead the president's security detail - two were eating dinner, and two were on standby.

Kim tried shooting the president again, but the pistol malfunctioned. He ran out to one of his men, who gave him a revolver. Having returned, he killed Cha a fleeing Cha, walked towards Park, who was leaning against the model as he bled, and shot him in the head.

The two women left unharmed after being paid to keep quiet. The president's chief of staff was never targeted.

Kim then went to the next building, where the army chief he had summoned earlier was waiting. The men left in a car for KCIA headquarters.

It's likely he didn't argue with Kim - even a shoe-less, suspiciously rattled Kim was powerful, and his men guarded the compound. But en route he was persuaded to go to army headquarters, where he was arrested soon after midnight.

Kim told the court he had planned to use the army, perhaps even impose martial law, to complete the "revolution" and transition to democracy.

This is the crux of the retrial. The prosecution had argued it was a premeditated coup, while Kim claimed far loftier motives.

But sceptics point to the lack of planning. The gun that jammed was plucked from a safe before dinner, there were enough witnesses to derail the plot, and he did not seem to have a strategy for his "revolution". He did not even make it to the KCIA headquarters.

Alamy

Alamy

Kim Jae-gyu during the trial

They say it may well have been an impulsive act of revenge by a man whose power was waning.

That's what the army general investigating the murders alleged two days later - Kim, second only to the president, had so much to lose as Park sidelined him in favour of Cha Ji-cheol.

The following month, he also charged Kim with attempting a coup.

"For a charge of insurrection to be proved, the accused must forcibly halt the function of constitutional institutions, but that didn't happen in this case," says lawyer Lee Sang-hee.

Unlike in impeached president Yoon's case - where the court will decide if he directed the military to block parliamentary proceedings - there is no evidence Kim Jae-gyu tried to seize control of state institutions, she argues.

For South Korea though, the retrial is more than that. Many see it as a defining moment to reflect on the trajectory of a democracy threatened just six months ago.

It is also an opportunity to re-evaluate Park Chung-hee, whose legacy some say is overstated. "His achievements were real, but so were his faults," says Kim Duol, an economics professor at Myungji University. "Would South Korea's growth have been possible without such an authoritarian regime?"

Kim's family hopes his retrial will shed a kinder light on his legacy. Killing Park was "a painful decision", Kim had told the court, but he had "shot at the heart of Yusin [the regime] with the heart of a wild beast".

Is that enough to make the former spy chief a hero? That is a question the court cannot answer.

2 months ago

27

2 months ago

27