My Ukrainian neighbours have fuelled my campaign to block Russian oil from Australia

By Mark Corrigan

November 21, 2025 — 5.00am

Like many kids educated in Australia during the Cold War era, my understanding of Eastern Europe was sparse and distorted. Crimea had something to do with an angelic Florence Nightingale of Victorian Britain. They had a lot of nuclear weapons. And they killed a dog by sending it into space.

Many decades on, the shooting-down of MH17 and intentional loss of so many civilian lives forced public, media and political attention towards what was unfolding along post-Soviet Russia’s fraught border with Ukraine. Even while engaging with that event, it was difficult to sieve out facts. The conflict appeared deliberately opaque, disguising Russian intervention as popular uprising. Whatever it was, it was still “over there”.

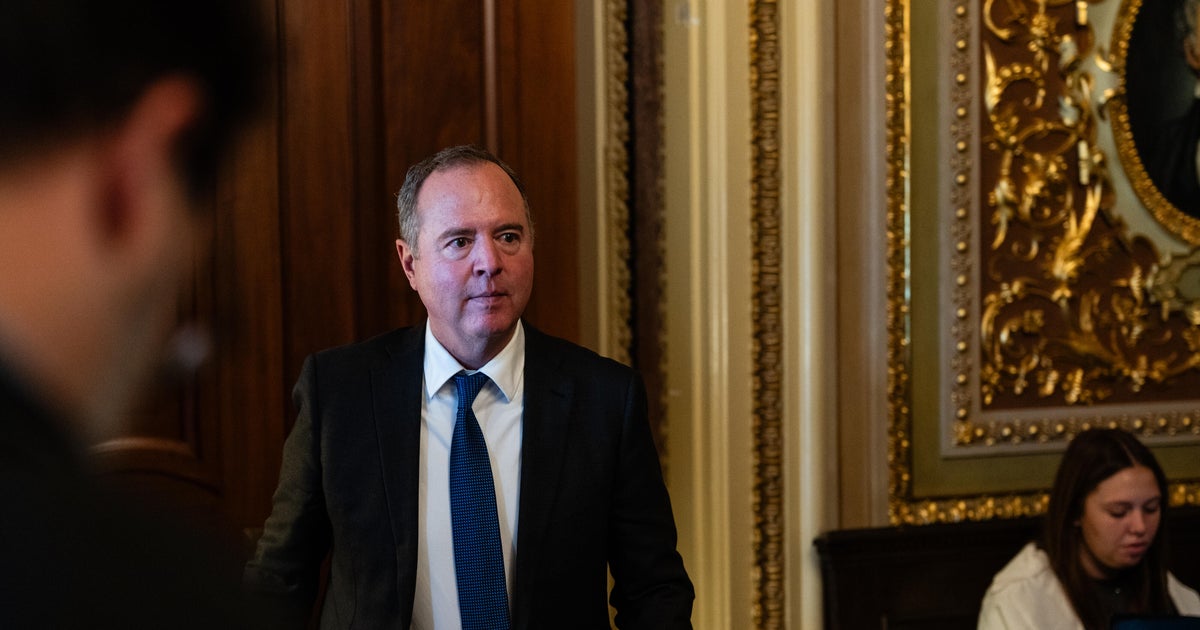

Mark Corrigan (far right) with his neighbours Tetiana and Oleksandr Tkachuk and their daughters Sophia and Kateryna. Credit: Sydney Morning Herald.

Several years later in 2021, as COVID lessened its hold over people’s lives, a young family who had just moved into our Hobart laneway came along to help the local Bushcare group. As I weeded and chatted with Tetiana, I learnt that they were Ukrainian and had been in Australia for only a few years. My ignorance soon showed when I asked her what language she spoke in Ukraine. Russian? “Ukrainian,” she said without a hint of exasperation.

The build-up of Russian forces along Ukraine’s borders in late 2021 was clearly more than a military exercise or feigned uprising. As the full-scale invasion of 2022 unfolded and reports of Russian military subjugating swaths of the once-Soviet country came out, I couldn’t help but think about the nice Ukrainian family down the lane that I barely knew.

Totally outside my comfort zone and hoping I wasn’t overstepping boundaries, I dropped over to let them know we cared for their wellbeing. They were clearly distressed, constantly following news feeds to get a perspective on what was happening in a rapidly evolving war zone.

As months went on, we got to know Tetiana, Oleksandr, their children, and Ukrainian friends and family who came to Tasmania to flee the destruction.

Loading

Tetiana’s grandfather, a man well into his 80s, took the interminably long trip from a small Ukrainian town to Tasmania to visit his granddaughters and great-grandchildren. This was a man who endured unbelievable post-World War II hardship, walking to school through snow without shoes, fearing planting potatoes because he might dig into the body of a buried soldier, and surviving on the maggot-ridden meat from their last cow because someone dug up and stole the fatherless family’s freshly planted potatoes. Yet, without a word of English, his optimistic personality transcended language barriers.

These were the people I was watching have their lives brutally upended simply because their country dared to forge their own way in the world without Russian oversight.

The war progressed and the world reacted, but it never seemed to be as fast, comprehensive or enthusiastic as the situation demanded.

Loading

Perhaps it was my background as a chemical engineer, but I began to take notice of Australia’s sanctions against Russian oil imports. I might not know a lot about munitions or battleground strategy, but commodities, manufacturing and data analysis are familiar territory.

Our ban on direct Russian hydrocarbon fuels seems simple on the surface. No crude oil or refined oil products originating in Russia can be imported to Australia.

I was shocked to find that “originate” has a particular meaning beyond normal usage. Some bureaucrats spend their lives devising “rules of origin” – frameworks that dictate when goods change from originating in one country to another. While crude oil may have come from Siberian oil wells, the act of separating fractions in a distillation column located in a third country meant Australia considered the fuel to be no longer Russian. It was effectively laundered.

Ukrainians I had come to know and care for were busy aiding their homeland or pulling themselves up by their bootstraps to create a new life in a strange country. Meanwhile, Australian importers were profiting from tanker after tanker of fuel from intermediate countries that were happily taking advantage of the discounted price of Russian crude.

Loading

The flow of Australian petrodollars to the Kremlin swamps the military and humanitarian aid our government has supplied to Ukraine.

It is this cruel policy dysfunction that has increasingly occupied my time over the past two to three years. I see India going from almost no Russian crude oil imports to Russia becoming their dominant supplier.

I see Australian importers increasing their flow of products from India despite the shady provenance.

I see Australian-sanctioned tankers firmly entrenched in our fuel supply stream, yet beyond the reach of our jurisdiction.

I see federal government inaction towards these policy loopholes and how they are aiding Russia in their brutal assault on people such as Tetiana’s grandfather.

I caught up with a friend recently. When he asked what I was up to, he got the three-minute version of campaigning against Russian oil in Australia. He replied with something I hadn’t stopped to consider: “Do you really think you can change anything?”

It was a depressing thought, but I guess I’ll never know if I stop now.

Mark Corrigan is a Hobart-based chemical engineer campaigning against Russian oil in Australia.

Most Viewed in Politics

Loading