There’s no number on the fence and no car in the driveway. This flat block of wet soil and tufty lush grass has a kind of bare and unfinished air, as if Michelle Payne’s old, white, weatherboard house was just plonked in the middle of a lonely paddock. The retired jockey’s farm sits somewhere north of Ballarat – a regional centre that always seems like the coldest place in Victoria – and it’s predictably, painfully frostbitten on this arctic August afternoon.

The whole chilly windswept patch is honestly so far removed from the pomp, pageantry and warmth of Melbourne’s spring racing carnival – the fabulous Flemington Racecourse roses, and champagne-soaked marquees, and fops and fillies stumbling drunkenly in all their hatted finery – that I briefly wonder if I’m in the right spot. I’m actually doubtful once I reach the front door, because it’s capped with a big pile of dried bird poo.

I rap my knuckles on the threshold anyway and with a delayed rustle and click she eventually emerges, the first and only female jockey to win “the race that stops a nation”. That was 10 years ago, of course, when Payne, then 30, sat atop the longest of longshots – 101-1 chance Prince of Penzance – yet won the day with a stunning ride, giving rise to a memoir (Life As I Know It) then a movie (Ride Like a Girl).

These days she’s a trainer and greets me with a high ponytail and shiny face, having scrubbed up after a bitter morning in and out of the stables. Leading me down a Baltic pine hallway to her lounge room, Payne chit-chats about the frigid weather in a thin, surprisingly tremulous voice, then perches on a cushy couch, knees hugged into her chest. Her feet snug under a warm brown blanket, a gas heater kicks on in the corner and the timbre of her voice deepens.

Payne’s got a tale to tell, and it’s not the gumboots-to-glory story you might expect following her famous victory. What came afterwards is a story about injury and exhaustion and risk, addiction and heartbreak and grief. And it starts back when she was a kind of national sporting fairytale come to life. Do you remember that day?

A triumphant Michelle Payne after winning the 2015 Melbourne Cup riding 101-1 shot Prince of Penzance.Credit: Getty Images

Payne was one of 24 jockeys (the other 23 being men) hoping to win the $6-million 2015 Melbourne Cup. An elfin 53-kilogram wisp on a muscular 500-kilogram beast, she remembers a slow start out of the barriers, the wall of sound from the grandstand, and how the tempo of the race – and her own heartbeat – quickened. With her toes in the stirrups, fingertips cinching the reins, the thoroughbreds came into the final turn with an almighty rumble. It was a notoriously messy race, rife with interference, but Payne found a magically faint crack in that chaos – a beautiful expanding gap that she could barrel safely into and beyond. Dropping her body flat below the wind, she asked the gelding beneath her to lengthen – nose pointed, ears pinned – and as the wave of horse flesh crashed into the home straight, the white blazing forehead of her big bay mount surged forward like foam over flat sand.

Dodging danger and streaking smoothly to the front, they scorched the entire blue-chip field together. Yet despite the surrounding whorl of power and violence, Payne now describes that moment as “the eye of the hurricane” – a place for her that was quiet. Somewhat serene. Safe, even.

“I think it’s fascinating how many thoughts you can have in such a high pressure race, with so much madness and extremeness going on,” she says, nodding. “Somehow you stay calm and think clearly. It was almost peaceful.”

The real storms came later.

If you read the coverage of what happened immediately after Payne dismounted and spoke to the media that day, you might think she gave the incendiary speech of a bully pulpit firebrand. Even now people abbreviate her whole message down to “GET STUFFED!” (often amplified with capital letters, and an exclamation mark). Yet listen to the tape more closely and her phrasing wasn’t some defiant one-two punch, but rather a measured sentence: “I just want to say to everyone else, get stuffed because they think women aren’t strong enough, but we just beat the world.”

Off the cuff, matter-of-fact, forthright, in her pinnacle moment. “I must have thought, ‘This is the right time to stand up for females,’ ” she now reflects. “We were still underrated, like it was a disadvantage to have a female rider. I had to say something.”

In her new book – Ride On: Hope, Healing and Getting Back on the Horse – she details a misogynistic continuum within the Sport of Kings, describing the struggles of trailblazers like Wilhelmina Smith (who raced in bush meets around Australia in the 1940s by posing as “Bill”) and Pam O’Neill (who had to wait until 1979 to become the first officially registered female jockey in this country). The youngest of 10 siblings, Payne naturally also talks about 1980s pioneers much closer to home, like her big sisters and jockeys Brigid, Therese and Maree, and also the sexism she herself faced in the saddle before winning the Cup, from people critical of everything from her physical strength to her reluctance to whip.

“I just want to say to everyone else, get stuffed because they think women aren’t strong enough, but we just beat the world.” Credit: Josh Robenstone

Greg Miles, the race caller who narrated a record 36 Melbourne Cups, points out that Payne came up in an era of “generic struggle” – meaning a prejudicial disinclination of older male trainers to use female jockeys. “It was still a battle,” Miles says. “But the change came with a wave, and Michelle rode the top of that wave.”

One small measure of what some now call “the Michelle Payne effect”? Ten years ago, 48 per cent of Racing Victoria’s apprentices were young women, whereas now the number is 77 per cent (clearly outnumbering men, 31 to nine). But it’s hard to shake those sexist slights. Even after her popular victory, star jockey Glen Boss was quoted in The Daily Telegraph and The Herald-Sun noting that Payne had a “bee in her bonnet” and might regret her post-race speech upon reflection.

“I don’t know if Glen was taken out of context, or he really meant it, and I don’t really care,” Payne says now with a quiet shrug. “He’s not a woman in a man’s world.”

Regardless, the overall response was more positive than negative, but even the afterglow of victory had drawbacks. Year on year there’s a story in whoever wins the Cup, but when that story emerges from outside the big stables and international owners? “A local 100-1 chance, ridden by a female jockey?” asks Victoria Racing Club (VRC) chairman Neil Wilson. “From that moment on – as with any jockey, trainer, owner – their lives change. But that was heightened for Michelle.”

‘My feet weren’t touching the ground. It was unbelievable madness. I’d won group one races and knew the buzz, but this was times a hundred.’

She did media all night, then got up at 6am to do 30 more interviews straight. (Yes, 30.) The requests kept coming. She would be in Washington, D.C. one week, Royal Ascot the next. “My feet weren’t touching the ground. It was unbelievable madness,” she says. “I’d won group one races and knew the buzz, but this was times a hundred.”

Even trips to the shops turned tiring, every errand taking longer as people stopped to say hello. The outpouring was lovely, yet she grew anxious and overwhelmed, sensing she could never quite meet the expectations of appreciative strangers. “I would say ‘Thank you’, but I didn’t know what else to say,” she says. “They’d stand there like they were waiting for me to do a backflip.”

People sent gifts and letters, which were often hard to reconcile. Boxes filled with socks or candles or T-shirts. Payne is religious and prays to God, so others began leaving pictures of Jesus at her gate. Soon it was no longer about what people wanted to give but what they wanted to take. “One guy requested a job and said he wanted a house with a queen-sized bed and a pool,” she says. “It was getting out of hand. People would just jump my fence and come onto my farm.”

A man was spotted taking surreptitious photos of her house. Harassing phone calls soon started. Frightening confrontations with stalkers. All of which required a huge security upgrade. Interestingly enough, there wasn’t a whole heap of sympathetic carry-on from her family about the fallout from her new-found fame. The Paynes are a tight clan, incredibly proud of one another but also utterly pragmatic, with little interest in any big-noting or hoo-ha.

“You’ve gotta take the good with the bad – that’s what I thought at the time,” says Andrew Payne, her big brother of six years, quite cheerily. “You wanted it desperately. You got the accolades. But there’s going to be some things you don’t like, too.”

Such blunt fatalism is born of their earnest origin story, of course. Payne’s mother and father met in New Zealand. Family lore recalls the day they decided to pool their entire savings and put it all on a horse he was training. The 200-1 longshot won, and they suddenly had enough money for a house. But because the Paynes are chancers as much as workers, they spent the winnings on new horses instead. One of those was Our Paddy Boy, a $NZ1300 weanling that turned into a champion and was sold for $300,000 in 1980 – a windfall that helped pay for their move to Australia.

Payne (at front) at the family home in Ballarat with siblings (from left) Maree, Bernadette, Patrick, Stevie and Therese.Credit: Courtesy of Michelle Payne

Michelle was the last born of their big brood. There might have been more, but her mother died six months later in a 1986 car accident, just down the road from home in Ballarat. People pitched in to help, of course, but the kids themselves became Michelle’s primary front-line carers. Family friend Jacqueline Moore visited the Paynes at home on the day of the tragedy, and was struck by the scene. “Not one of them was crying,” Moore remembers. “They’re an interesting bunch. The most non-emotional people I know. They just got on with it – and cracked on. But I sometimes wonder if that stoicism has a cost.”

‘You have to be doing something you love, and you have to be a bit mad, too. That’s the way with any athlete.’

Being a jockey is incredibly dangerous, after all. There aren’t many sports where an ambulance speeds along behind every contest. Like all riders, Payne suffered more than a few serious falls, but the one that really rocked her came in 2016, just a year after her big victory. She doesn’t remember flying over the front of Dutch Courage in Mildura – only the pain that followed after the young mare trampled her.

“Horrendous. It was horrendous,” Payne says. “I remember waking up on the ground in agony. I knew I was bleeding internally, straight away, I don’t know how.”

Payne falling off Dutch Courage in Mildura in 2016; “It was horrendous,” she recalls.

The medical team tried for 45 minutes to get her onto the stretcher, but Payne had scrunched herself into a protective ball, refusing to uncurl. “Finally when they gave me the morphine, they could lay me out flat. I was in another world,” she says. “But in the lead up to that fall I didn’t know how I was going to go on, because it was all just so much. The fall actually gave me a chance to reset.”

Airlifted to Melbourne’s Alfred Hospital, her pancreas had been smashed to pieces and required an unusual operation to salvage the fraction that worked while stitching the remains to her stomach. She remembers weeks of chapped lips and regurgitating ice chips, epidurals that barely touched the sides, and nightmarish hallucinations of gremlins and devils. Soon, though, she began walking slowly around the ward – two laps, just like in the Cup – and found other patients joining her, often trailed by their family and friends in a shuffling, sorry, smiling convoy. She’s still managing the effects of the fall almost a decade later.

“I’m very good at reading myself and my energy levels,” she says. “I just stick to a very basic diet. Lots of steamed vegies, lots of protein shakes, easy-to-digest food that I can get my nutrients from without my body having to work too hard to break it down.”

The family rallied around her and even raised the touchy subject of her racing mortality. “That was one of my horses, so it hits closer to home,” says big brother Patrick, who now runs a training operation an hour from Melbourne in partnership with his little sis. “That’s when I said, ‘Why do you want to keep risking it?’ But you also can’t make the decision for her. The old man is Irish, and she’s very pig-headed herself.”

With brother Patrick; they run a training operation together.Credit: @michellejpayne_/Instagram

It’s a fair question, though. Just last month, their nephew Tom Prebble (son of sister Maree and brother-in-law Brett Prebble, also a retired Melbourne Cup-winning hoop) fell during a race at Warrnambool, necessitating spinal surgery. Prebble is apprenticed to Michelle and Patrick, and had just begun emerging as a young star this winter. The full extent of his injuries remains unclear, and the family – which has asked for privacy – is understandably still reeling from the accident.

Payne was no stranger to potentially catastrophic injuries, either, including a fractured skull with bleeding on the brain, and breaks in the neck and back. Five female jockeys had died in the three years prior to her fall on Dutch Courage. And looming over all of this is her big sister Brigid, the eldest of the Payne siblings, who died of a heart attack following a series of aneurysms in 2007, six months after falling heavily during barrier practice. Brigid was just 36. Knowing all that, why keep going?

Payne answers carefully – neither expansive nor reserved – with soft eyes that hold their gaze. She ends her sentences where they’re supposed to end, riding them right up to the finish and no further. “Everyone asked me in every single interview, ‘Are you going to retire?’ ” she says, pausing. “I left the decision up to my gut. I didn’t want to put any pressure on myself straight away, and I wasn’t going to let myself be scared off it, either. Don’t restrict your living by being afraid of dying.”

She’s happy she returned to the saddle, too, enjoying some of her favourite wins in subsequent years, unencumbered by the need to prove anything. The joy is in the exhilaration, pressure and sometimes, she admits, even the danger. But the partnership with the animal is where she gets sentimental, even romantic.

Riding a horse aged 11.Credit: Courtesy of Michelle Payne

“It’s the most beautiful thing, where literally you can move your little fingers or lower your body weight an inch, and they feel it and give you everything they have,” she says. “That sensitivity, from such beasts, is just amazing.”

She tells me about the horses outside right now, like Bully (race name Bullitt County), a “nanny” who watches over younger horses - her sweetheart who would take care of anyone who sat on his back. “You look at his face and he instantly makes you smile,” she says. “He comes up and waits for you to hold his face and give him a kiss.”

Horses to her aren’t just animals but anthropomorphic companions, likened to everything from dinosaurs to kangaroos and clowns – pets, friends and empaths – but also rebels, bluffers and bastards. They are her everything.

Touching softness aside, Michelle Payne has also always possessed a particular blunt savvy. “Even at three years of age, I could never put anything past her,” says Andrew, laughing. “I could not trick her. She was always sharp, always watching.”

She was a cute kid and good at school, which didn’t sit so well with her less academic siblings, who used to call her “Stink” for no other reason than the funny outburst their teasing would prompt. Michelle was never afraid to speak up or out. Patrick remembers a time when she was seven years old and a religious group came door-knocking, asking if anyone in the house had money to spare. “Yeah, I’ve got some money,” said Stink, “but I’m not wasting it on you people.”

That nature never faded, and in the years since her win and then fall, Payne emerged not just as a talking head but a reliably strident voice in racing. “It’s part of my personality, and probably the way we were brought up,” she says. “When you’re one of 10, you have to stick up for yourself. And if you have a platform, why wouldn’t you use it for good?”

That’s a reference to more than a handful of times in more recent years in which she either became a news story herself or waded into a topic or controversy because she felt obliged. “She’s definitely happy to have a point of view,” says Wilson of the VRC. “Often with some risk attached.”

In 2018, for instance, she successfully fought against a rule in NSW that denied her the right to be a dual license jockey and trainer (already allowed elsewhere), and was in turn praised by Racing NSW boss Peter V’landys, a kindred straight-talker. “Without the determination and drive of Michelle Payne,” V’landys said, “this may not have come to fruition.”

She pulled no punches in criticising tracks for being too hard, got fined by stewards for doing so, but doubled down online anyway, with a post on the social media platform Twitter (rebranded as X): “Likely to scratch Sweet Rockette if the track looks too firm. And cop another fine for looking after my horse and owners. Absolute bullshit.” (The upshot? A $300 fine for Payne, but a change was made also to ensure tracks would have enough softness and give, especially at the height of summer.)

Then in 2019, when jockey Linda Meech was dumped from her Victoria Derby ride only a few days before the race, Payne was stunned, having weeks earlier seen Meech ride the horse, Thought of That, when it was “really colty and misbehaving”.

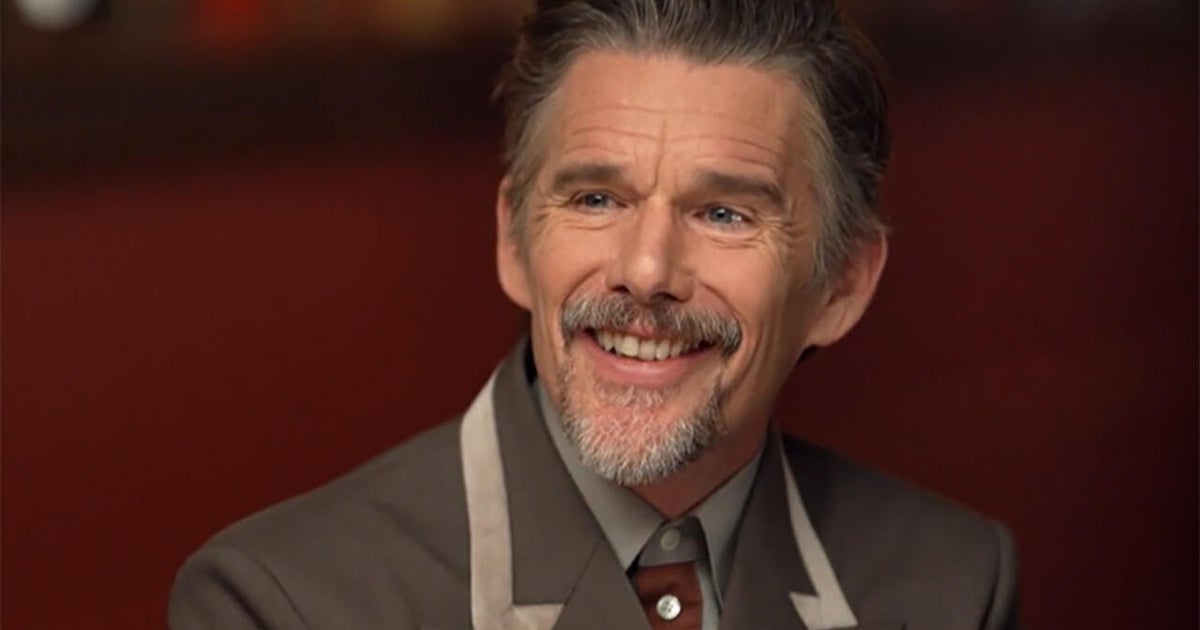

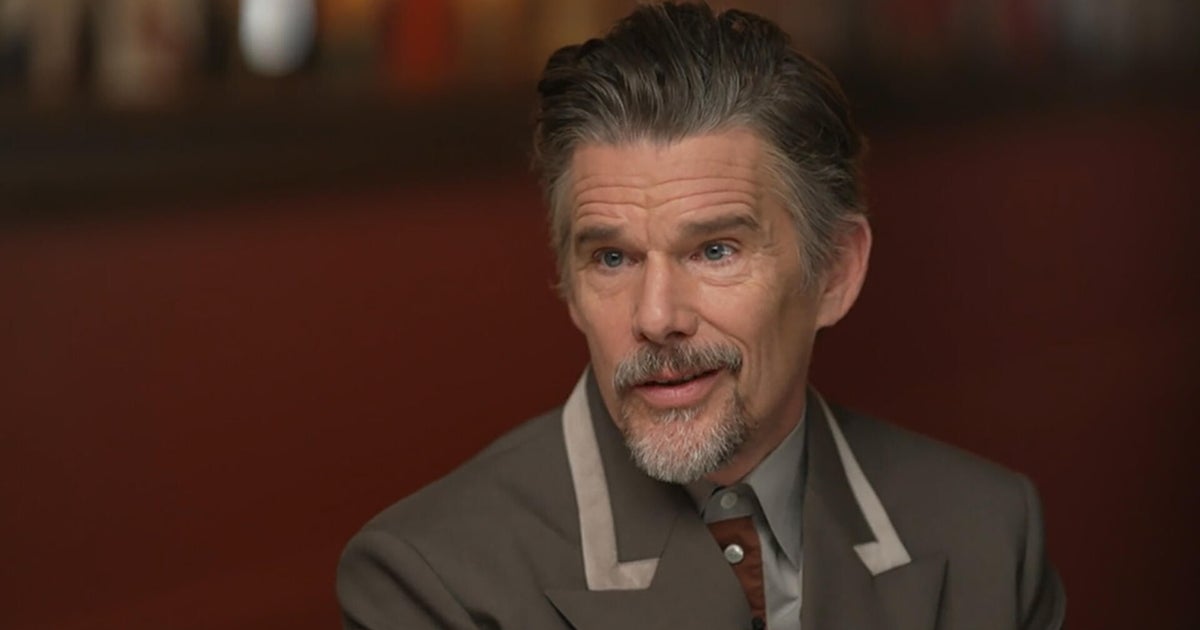

“You have to be doing something you love, and you have to be a bit mad, too,” Payne reckons. “That’s probably the way with any athlete. You just have to be a different breed.”Credit: Josh Robenstone

“I was in the race,” Payne says. “Another jockey might have said, ‘Stuff this, take that horse away, it’s crazy’, but she rode the horse and won on it, then she won on it again. It wasn’t winning before that.”

Trainer Brae Sokolski said he knew his decision would be unpopular, but also that it was “not a decision for the public”. Payne fired back online – “Not for the public to decide, but the public can recognise you as a pig” – and got fined again. Unfortunately, she hadn’t realised that Sokolski is Jewish and would take far greater offence at the slight. “I didn’t know; I just thought it was a soft subtle way of saying something,” she says now. “But it was the way I said it, not what I was saying.”

Loading

From time to time, she even talks face-to-face with anti-racing and “Nup to the Cup” protesters, walking up to placard-holders in Warrnambool or Oakbank for a chat about the bond she forms with her horses, and the devastation she feels when they’re injured (or worse). “They wouldn’t hear anything, just yelling in my face; I found it fascinating,” she says. “They can’t fathom that a positive side to racing exists.”

And in some ways that’s fair enough, considering the likes of Darren Weir, the trainer of Prince of Penzance, who was much later disqualified from training for six years after using an electronic shock device known as a “jigger” on other horses. Leaked footage of the practice was shared publicly only last month. “Darren is such a good horseman and trainer,” she says. “He never needed to do any of that stuff, and there’s no place for it in the sport.”

Payne is a public figure – an expert analysis commentator for Nine (part of Nine Entertainment, the owner of this masthead), and a Melbourne Cup ambassador to boot – wheeled out recently to a steady stream of events and dress fittings, but she doesn’t love the attention. Whenever the spotlight gets tough, she thinks of the words of her hero, Roger Federer, who she was lucky to meet in 2016 and who gave her some sage advice. “It’s nice to be important,” he told her, “but it’s more important to be nice.”

I wonder what Payne hated about riding, and her list is immediate and long, from the recurring 3am alarm clock to the euphemistic practice of “reducing”: trying to lose kilograms quickly through running in a sweat suit or simple starvation. She recently became friends with swimmer Ariarne Titmus and marvels at the Olympian’s own masochistic streak, spending all those hours in a pool, up and back, over and over. “You have to be doing something you love, and you have to be a bit mad, too,” Payne reckons. “That’s probably the way with any athlete. You just have to be a different breed.”

That’s not why she gave racing away, however. That came courtesy of multiple concussions. She was on the farm a year ago when a bird gave her horse a fright, causing its hard head to jerk back and smash her in the face. A week later, the same thing happened. (She saw stars this time, and felt blood in both nostrils.) A week later, another knock in similar circumstances. “It was just really bad,” she says, shaking her head. “The sequence compounded everything, because there was no rest between them.”

Loading

Payne grew concerned by lingering mood swings and memory loss, lethargy and a lack of focus. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) can only be diagnosed after death, but scans discovered atrophy in a small section of her brain. “Undamaged nerve endings can take over the job of the ones that are damaged, so you definitely stay positive and keep a healthy lifestyle,” she says. “But I’ve taken a step back from training on my own, too, because the pressure and not getting enough rest just wasn’t helping.”

These days she wakes up with the sun and will jump on a horse for the occasional gallop, but no more trackwork at dawn. She joined forces with her brother Patrick as a trainer and goes to a handful of race meetings a month. He says his sister has found a good lane. “What else does she really need to do?” Patrick asks. “She’s achieved, and been through the other side, and seen that it wasn’t so good. I think she wants to be a happier person.”

Being a happier person is a reference to the penultimate calamity of Payne’s life so far: the death of her big sister Bernadette, only seven months ago. Bernadette was the one who – at just 12 years old and grieving the loss of their mum – would brave the cold in the middle of the night to give baby Michelle a bottle, then lay beside her until she slept.

“Bernie” was a free spirit – silly and stubborn, loyal and easygoing – but she was kicked and trampled during a riding accident in Horsham when she was 21. Her shoulder was badly broken that day, and the pain stayed with her for decades. The painkillers did, too, unfortunately. Her mental health suffered, yet despite family interventions Bernie didn’t want to see a psychologist, instead looking for answers with psychics and healers. She tried working as a trainer with their dad, but as her addiction took hold there were tantrums and torment, incoherence and darkness.

“She would have been numbing the pain, or numbing a depression, or maybe both. Probably both,” Payne says. “But by the end she was unrecognisable – Who is this person? – and scary. I had an intervention order against her.”

Payne tries to remember the good things, but photo albums of them playing dress-ups together make her cry. “I just remember asking her, ‘What do you want?’ and the answer was so sad,” she says. “She said, ‘I don’t want anything. I just want to go back to when we were little kids and everybody was playing together in the puddles and laughing.’ But she just wouldn’t accept any help.”

With big brother Stevie, who was her Melbourne Cup strapper and king to her Moomba queen.Credit: Getty Images

The wound is still fresh, and Payne still wonders if there was anything more they could have done. After Bernie died, they found some notes among her things: “Think you can’t go on?” she wrote. “Change might be just around the corner.” It looked like she wanted to help herself but couldn’t quite get over the line, and instead joined the 3000 “broken spirits” who take their own lives every year in this country. “I talk about it – without any answers – because maybe someone going through a similar thing will come up with an idea, a different path,” Payne says. “Or maybe they won’t feel alone.”

Loading

Payne isn’t alone, incidentally. Her closest sibling in age, big brother Stevie – who has Down syndrome and was her best friend growing up – lives in a granny flat behind her house. He’s a skilled “strapper”: hosing and brushing and grooming and feeding and loving all their pretty horses with massages and songs and kisses. Stevie became part of her famous story, too, when, as her strapper, he drew the prized barrier one in the Melbourne Cup. After the win, they were king and queen of Melbourne’s annual Moomba festival. The big mantle in her lounge is filled with board games they play together, from Match Madness to Sequence.

“Have you ever played Balderdash?” she asks. “Very fun. Really funny. Great for the imagination. Stevie kills me at Sequence. He’s amazing.”

That mantle is filled with trophies, too, like the gold-plated Harry White whip given to the winning jockey of the Cup. Not to mention framed photos of family members and country cup victories she’s had along the way, all hung crooked as hell.

She’s got a cozy spread here. Wearing a jumper with the words “Be intrigued” on the front, she leads me out through her messy mud room for a little drive on her block, past the stables and the treadmill and out to those cold paddocks, surrounded by cypress trees she planted in rows as windbreaks.

Payne ducks under an electric fence to say “Hey guys!” to Prince of Nottingham and Silver Pledge and Stop the Rock. And they follow her after we leave, too, loping and trotting and galloping beside her car, hoping to stay close. She loves her proximity to fresh air and peace, even when drifting back into heady memories of the thunderous race that changed her life.

“My mind goes to my disbelief,” she says. “It is so hard just to get into the field, let alone have everything working in your favour to win it. It’s crazy to think that all the stars aligned.

“Then what came later? I still shake my head,” she continues, her head remaining perfectly still. “It was tricky to navigate, but that’s life. You’ve gotta take what comes your way, and make the most of everything.”

Lifeline 13 11 14

To read more from Good Weekend magazine, visit our page at The Sydney Morning Herald, The Age and Brisbane Times.