Last year, high-flying chef Teage Ezard, 59, was diagnosed with a rare neurological disorder with no known cure. With his symptoms progressing, he and his wife, Tina, 54, contemplate their future and celebrate their past.

Teage: I never thought I’d have an incurable disease, but it’s happened. It’s rare, it’s in the brain. I’ve done my best to prepare Tina for my demise. When I met her in my late 30s, I had the world at my feet. Now I’ve lost my purpose, potential, energy and independence and she’s the primary caregiver for me and our teenage son and daughter. She’s my rock.

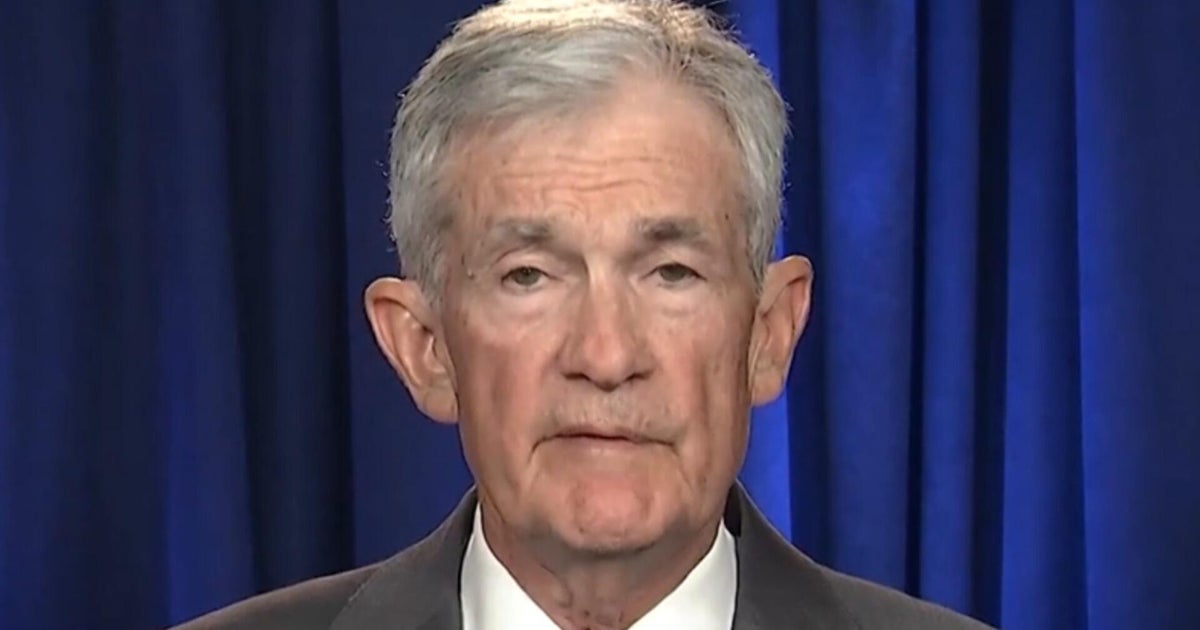

Teage and Tina Ezard: “Loving someone with a progressive, incurable disease forces you into a grief that keeps unfolding,” Tina says.Credit: Peter Tarasiuk

My feelings for her now are just as intense as the first time I laid eyes on her at the Melbourne Grand Prix in 2003. I asked her out, she said no. I kept trying to woo her and, eventually, she said yes. I was living in the fast lane. I had [fine-dining Melbourne CBD restaurant] Ezard and it was moving towards three [Good Food Guide] hats.

Tina wasn’t just attractive, she was stable. We had very different upbringings. She had a mum and dad, a home. My mum was on welfare and I moved 17 times as a kid. All the kids I went to school with are either in prison or dead.

Cooking gave me purpose, meaning and discipline, but when I met Tina, I wasn’t sure who I was; I was still trying to find my feet. I’d enter the kitchen at 10am, put on Mozart, drink a VB. If you cut your finger, you’d stick it in hot oil.

I proposed within six months and we got married in Bali. Tina let me chase my dreams. I started bouncing important decisions off her. She helped me with business relationships: I was always “let’s get shit done”; she was “how are you?” We complemented each other.

I was first married at 22 and had two girls pretty young. I wasn’t the perfect father: business came first, family second. I did things differently with Tina, involved her more, loved her more, but I was constantly working.

Around 2016, I lost my mojo. I felt tired, had no motivation. I couldn’t be on a travelator without holding on. I went through so many tests in so many hospitals. Finally, getting a diagnosis [of multiple system atrophy cerebellar type] last October was a relief. I was scared of dying after the initial shock of the diagnosis, but I’ve accepted time isn’t on my side.

‘It’s hard to have your independence taken away. Tina reassures me …Her strength and patience leave me in awe.’

Teage EzardUnfortunately, I’m going to decline. It’s hard to have your independence taken away. Tina reassures me, helps me engage in social interactions, monitors my symptoms. Her strength and patience leave me in awe. As a society, we should talk more about death. Death should be celebrated if you can be peaceful, without struggle, if you leave a legacy. I don’t have regrets, I didn’t leave any stone unturned, but I’ve realised if you’re too busy in life, you miss out on what’s important. The diagnosis has brought me closer to my children; I’m vulnerable now and I assure them this isn’t hereditary. Tina’s love is steady. Her presence gives me peace.

Tina: When we met, work was my everything and I was happy to cruise through life and have a baby on my own. I was working at the grand prix as a business development manager for a mineral water brand. We’d invited some high-profile chefs along and Teage was one of them. He was quite drunk and I ended up chucking him in a cab and slamming the door. Three months later, I was at the George bar in St Kilda with friends. He walks in and sits next to me: “You’re going to come on a date”; “No, I’m not, actually.” He kept pursuing me. We started dating and that was it.

Teage was open, passionate about life. He’d been doing therapy, trying to find how broken he was and why his relationships fell apart. He was vulnerable. He’d say things like “see how bright the sky is?” He was really raw and I enjoyed that. He’d wake in the middle of the night after crazy dreams. I said “write them down”. He had ideas for all his restaurants [Ezard and Gingerboy in Melbourne, Black by Ezard in Sydney and Ezard at Levantine Hill in the Yarra Valley]. He had this amazing brain. It was attractive to see somebody function at this euphoric level.

‘You lose parts of the person before they’re physically gone.’

Tina EzardThe restaurants made for long, fast hours; the work didn’t stop. If we weren’t trying to fix a menu, do tastings or get a new product, we’d travel to eat, locally and overseas. I helped him. I was happy, quietly behind closed doors. I’d tell Teage “believe in your instinct, your passion, because nothing can be a failure then”. We’ve had two kids – Sienna is 18, Kingston is 16 – but the restaurants were always Teage’s first family, first love. I didn’t mind: I love seeing people grow.

By 2017, he’d become withdrawn, flat, unusually anxious. By the time COVID-19 hit, he had severe depression, apathy. He had no dexterity for cooking and his palate was changing: he kept asking for more salt, chilli, lime. It was confronting. I said “let’s get out of the business – for your mental health”. The lease was coming up at Ezard in 2020 and he waited ’til the last day to decide to shut it down. He was struggling. He wasn’t talking, couldn’t get out of bed.

I said “we’re alive, we’re breathing, we’ve got our kids. We’re OK,” but it’s hard when you’ve been so successful and then, all of a sudden, it’s gone. We knew his balance wasn’t right. He kept saying “I feel like I’m on a boat”. He crashed the car. He’d thrash out in his sleep, scream like he was in a kitchen, “Five minutes, chef!” Now we know these are all MSA symptoms.

Loading

When we eventually found out what it was, it was hard but validating. He won’t be able to talk soon, maybe within a year. Loving someone with a progressive, incurable disease forces you into a grief that keeps unfolding. Even when you’re in the same room, the distance grows. You lose parts of the person before they’re physically gone: his independence, speech, intimacy, shared jokes, late-night talks, spontaneous hugs, the conversations you didn’t know were precious.

Loneliness is part of my life now. We’re celebrating Teage’s life, too. We’ve got a daughter doing high-school exams, a son who needs his dad. The children see the changes. They feel awkward, powerless. They’ve lost the dad who drove them to school, gave them tips in the kitchen. I’ve lost a partner but, for the most part, I carry my grief silently. Someone has to hold it all together.

Most Viewed in National

Loading